这是关于Alisdair Owen的PostgreSQL练习的所有问题和答案的汇编。请记住,实际解决这些问题将使您不仅要浏览本指南,因此请确保支付后Ql练习的访问。

进行练习非常简单:您要做的就是打开练习,看看问题,然后尝试回答它们!

这些练习的数据集用于新创建的乡村俱乐部,其中包括一套成员,网球场等设施以及为这些设施的预订历史。除其他外,俱乐部想了解他们如何使用信息来分析设施的使用/需求。请注意:此数据集纯粹是为了支持有趣的练习阵列,并且数据库模式在几个方面存在缺陷 - 请不要以它为良好设计的示例。我们将从查看会员表开始:

CREATE TABLE cd .members

(

memid integer NOT NULL ,

surname character varying ( 200 ) NOT NULL ,

firstname character varying ( 200 ) NOT NULL ,

address character varying ( 300 ) NOT NULL ,

zipcode integer NOT NULL ,

telephone character varying ( 20 ) NOT NULL ,

recommendedby integer ,

joindate timestamp not null ,

CONSTRAINT members_pk PRIMARY KEY (memid),

CONSTRAINT fk_members_recommendedby FOREIGN KEY (recommendedby)

REFERENCES cd . members (memid) ON DELETE SET NULL

);每个成员都有一个ID(不能保证是顺序的),基本地址信息,对推荐它们的成员的引用(如果有)以及它们加入时的时间戳。数据集中的地址是完全(不切实际)的。

CREATE TABLE cd .facilities

(

facid integer NOT NULL ,

name character varying ( 100 ) NOT NULL ,

membercost numeric NOT NULL ,

guestcost numeric NOT NULL ,

initialoutlay numeric NOT NULL ,

monthlymaintenance numeric NOT NULL ,

CONSTRAINT facilities_pk PRIMARY KEY (facid)

);设施表列出了乡村俱乐部拥有的所有可预订设施。俱乐部存储ID/名称信息,预订会员和客人的费用,建造设施的初始成本以及估计的每月维护费用。他们希望使用这些信息来跟踪每个设施的财务价值。

CREATE TABLE cd .bookings

(

bookid integer NOT NULL ,

facid integer NOT NULL ,

memid integer NOT NULL ,

starttime timestamp NOT NULL ,

slots integer NOT NULL ,

CONSTRAINT bookings_pk PRIMARY KEY (bookid),

CONSTRAINT fk_bookings_facid FOREIGN KEY (facid) REFERENCES cd . facilities (facid),

CONSTRAINT fk_bookings_memid FOREIGN KEY (memid) REFERENCES cd . members (memid)

);最后,有一个桌子跟踪设施的预订。这存储了设施ID,进行预订的成员,预订的开始以及预订的半小时“老虎机”。这种特殊的设计将使某些查询更加困难,但应该为您提供一些有趣的挑战 - 并为使用一些现实世界数据库的恐怖做好准备:-)。

好的,那应该是您需要的所有信息。您可以从上面的菜单中选择一个类别的查询,也可以从一开始就开始。

没问题!起床并运行并不难。首先,您需要安装PostgreSQL,您可以从这里获得。启动后,下载SQL。

最后,运行psql -U <username> -f clubdata.sql -d postgres -x -q创建“练习”数据库,Postgres'PGEXERCERS'PGEXERCESS'用户,表格,并加载数据。请注意,请注意,您可能会发现,您可能会在网站上使用perge的范围,因为该端口与网站相差不同,因为该pers可能会在网站上设置:这是一个不同C语言环境)

当您运行查询时,您可能会发现PSQL有点笨拙。如果是这样,我建议尝试使用PGADMIN或Eclipse数据库开发工具。

此类别涉及SQL的基础知识。它涵盖了选择,案例表达式,工会以及其他一些赔率和终点。如果您已经在SQL中受过教育,则可能会发现这些练习相当容易。如果没有,您应该发现它们是开始学习未来更困难的类别的好点!

如果您在这些问题上挣扎,我强烈建议Alan Beaulieu撰写的SQL,作为一本关于该主题的简洁而精心编写的书。如果您对数据库系统的基础知识感兴趣(而不是如何使用它们),则还应通过CJ日期调查数据库系统的简介。

如何从CD.FICICITIONS表中检索所有信息?

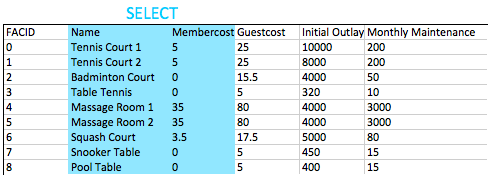

预期结果:

| FACID | 姓名 | 成员代表 | 来宾代表 | 初始OUTOUTLAY | 每月保养 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 网球场1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | 网球场2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | 羽毛球法院 | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | 乒乓球 | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | 按摩室1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | 按摩室2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | 壁球场 | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker表 | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | 泳池表 | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

回答:

select * from cd . facilities ; SELECT语句是查询的基本起始块,这些查询是从数据库中读取信息的。最小的选择语句通常select [some set of columns] from [some table or group of tables]组成。

在这种情况下,我们希望从设施表中的所有信息。从节很容易 - 我们只需要指定cd.facilities表即可。 “ CD”是表格的架构 - 用于数据库中相关信息的逻辑分组的术语。

接下来,我们需要指定所有列。方便地,有一个“所有列”的速记 - *。我们可以使用它,而不是费力地指定所有列名。

您想打印出所有设施及其成本的清单。您如何检索仅设施名称和成本的列表?

预期结果:

| 姓名 | 成员代表 |

|---|---|

| 网球场1 | 5 |

| 网球场2 | 5 |

| 羽毛球法院 | 0 |

| 乒乓球 | 0 |

| 按摩室1 | 35 |

| 按摩室2 | 35 |

| 壁球场 | 3.5 |

| Snooker表 | 0 |

| 泳池表 | 0 |

回答:

select name, membercost from cd . facilities ; 对于这个问题,我们需要指定所需的列。我们可以使用指定为选择语句的简单逗号列表的简单逗号列表来做到这一点。所有数据库所做的就是查看从子句中可用的列,然后返回我们要求的列,如下所示

一般而言,对于非throwaway查询,可以认为可以在查询中指定所需的列的名称而不是使用 *。这是因为如果将更多列添加到表中,您的应用程序可能无法应对。

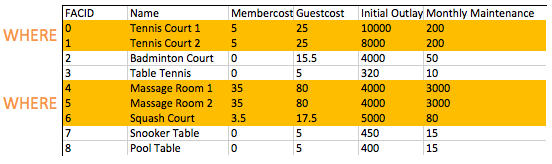

您如何制定向会员收取费用的设施清单?

预期结果:

| FACID | 姓名 | 成员代表 | 来宾代表 | 初始OUTOUTLAY | 每月保养 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 网球场1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | 网球场2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 4 | 按摩室1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | 按摩室2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | 壁球场 | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

回答:

select * from cd . facilities where membercost > 0 ; FROM子句用于建立一组候选行以读取结果。到目前为止,在我们的示例中,这组排只是表的内容。将来我们将探索加入,这使我们能够创建更多有趣的候选人。

一旦我们建立了一组候选行, WHERE子句允许我们过滤我们感兴趣的行 - 在这种情况下,成员代表的成员超过零。正如您将在以后的练习中看到的那样, WHERE条款可以具有多个组件与布尔逻辑相结合 - 例如,可以搜索其成本大于0且小于10的设施。设施上的WHERE子句的过滤操作如下:

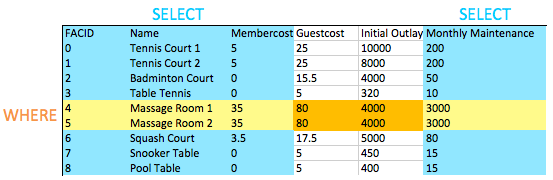

您如何制定向会员收取费用的设施清单,而该费用少于每月维护成本的1/50?返回相关设施的FACID,设施名称,会员成本和每月维护。

预期结果:

| FACID | 姓名 | 成员代表 | 每月保养 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 按摩室1 | 35 | 3000 |

| 5 | 按摩室2 | 35 | 3000 |

回答:

select facid, name, membercost, monthlymaintenance

from cd . facilities

where

membercost > 0 and

(membercost < monthlymaintenance / 50 . 0 ); WHERE条款允许我们过滤我们感兴趣的行 - 在这种情况下,成员成员的成员超过零,少于每月维护成本的1/50少于1/50。如您所见,由于人员配备成本,按摩室运行非常昂贵!

当我们要测试两个或多个条件时,我们会使用AND结合它们。如您所期望的那样,我们可以使用OR测试一对条件中的任何一个是正确的。

您可能已经注意到,这是我们的第一个查询,将WHERE子句与选择特定的列相结合。您可以在下面的图像中看到以下效果:所选列和所选行的相交为我们提供了返回的数据。现在似乎不太有趣,但是正如我们添加了更复杂的操作,例如加入后来,您会看到这种行为的简单优雅。

您如何以其名称以“网球”一词的形式制作所有设施的列表?

预期结果:

| FACID | 姓名 | 成员代表 | 来宾代表 | 初始OUTOUTLAY | 每月保养 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 网球场1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | 网球场2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 3 | 乒乓球 | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

回答:

select *

from cd . facilities

where

name like ' %Tennis% ' ; SQL的LIKE运营商在字符串上提供了简单的模式匹配。它几乎是普遍实现的,并且既易于使用又易于使用 - 它只需带一个符合任何字符串字符的字符串,_匹配任何单个字符。在这种情况下,我们正在寻找包含“网球”一词的名称,因此在任何一边都贴上一个%的账单。

还有其他方法可以完成此任务:例如,Postgres支持与操作员的正则表达式。使用让您感到舒适的任何东西,但请注意, LIKE操作员在系统之间更便携。

您如何使用ID 1和5检索设施的详细信息?尝试在不使用或操作员的情况下执行此操作。

预期结果:

| FACID | 姓名 | 成员代表 | 来宾代表 | 初始OUTOUTLAY | 每月保养 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 网球场2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 5 | 按摩室2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

回答:

select *

from cd . facilities

where

facid in ( 1 , 5 ); 这个问题的明显答案是使用WHERE看起来像where facid = 1 or facid = 5子句。在IN符中,有大量可能的匹配项更容易。在运算IN获取可能的值列表,并将它们与(在这种情况下)facid匹配。如果其中一个值匹配,则该行的where子句为true,然后返回行。

IN符是关系模型优雅的良好早期演示者。它采取的参数不仅是值列表 - 它实际上是一个带有单列的表。由于查询也返回表,因此如果您创建一个返回单列的查询,则可以将这些结果馈送到IN员中。举一个玩具例子:

select *

from cd . facilities

where

facid in (

select facid from cd . facilities

);该示例在功能上等同于仅选择所有设施,但向您展示了如何将一个查询的结果馈送到另一个查询的结果。内部查询称为子查询。

您如何制作设施列表,每个设施都标记为“便宜”或“昂贵”,具体取决于其每月维护成本是否超过100美元?返回有关设施的名称和每月维护。

预期结果:

| 姓名 | 成本 |

|---|---|

| 网球场1 | 昂贵的 |

| 网球场2 | 昂贵的 |

| 羽毛球法院 | 便宜的 |

| 乒乓球 | 便宜的 |

| 按摩室1 | 昂贵的 |

| 按摩室2 | 昂贵的 |

| 壁球场 | 便宜的 |

| Snooker表 | 便宜的 |

| 泳池表 | 便宜的 |

回答:

select name,

case when (monthlymaintenance > 100 ) then

' expensive '

else

' cheap '

end as cost

from cd . facilities ; 本练习包含一些新概念。首先是我们在SELECT和FROM的查询区域进行计算。以前,我们仅将其用于选择要返回的列,但是您可以将任何内容都放在每个返回行(包括子查询)中会产生单个结果。

第二个新概念是CASE陈述本身。 CASE实际上就像其他语言中的/开关语句一样,其形式如查询所示。要添加“中间”选项,我们只需when...then插入另一个选项。

最后,有AS操作员。这仅用于标记列或表达式,以使其显示更精美,或者在用作子查询的一部分时使其更易于参考。

您如何制定2012年9月开始后加入的成员名单?返回有关成员的MEMID,姓氏,名称和加入。

预期结果:

| 梅德 | 姓 | 名 | 加入 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 萨尔文 | 拉姆纳雷什 | 2012-09-01 08:44:42 |

| 26 | 琼斯 | 道格拉斯 | 2012-09-02 18:43:05 |

| 27 | 拉姆尼 | 亨利埃塔 | 2012-09-05 08:42:35 |

| 28 | 法雷尔 | 大卫 | 2012-09-15 08:22:05 |

| 29 | Worthington-Smyth | 亨利 | 2012-09-17 12:27:15 |

| 30 | 范围 | 米里森 | 2012-09-18 19:04:01 |

| 33 | 特百惠 | 风信子 | 2012-09-18 19:32:05 |

| 35 | 打猎 | 约翰 | 2012-09-19 11:32:45 |

| 36 | 碎屑 | 埃里卡 | 2012-09-22 08:36:38 |

| 37 | 史密斯 | 达伦 | 2012-09-26 18:08:45 |

回答:

select memid, surname, firstname, joindate

from cd . members

where joindate >= ' 2012-09-01 ' ; 这是我们对SQL时间戳的首次浏览。它们以降序的数量级格式: YYYY-MM-DD HH:MM:SS.nnnnnn 。我们可以像Unix Timestamp一样比较它们,尽管在日期之间获得差异的参与度更高(而且强大!)。在这种情况下,我们刚刚指定了时间戳的日期部分。这将被Postgres自动投入到整个时间戳2012-09-01 00:00:00 。

如何在成员表中产生前10个姓氏的有序列表?该列表不得包含重复项。

预期结果:

| 姓 |

|---|

| 坏人 |

| 贝克 |

| 展位 |

| 黄油 |

| 科普林 |

| 碎屑 |

| 敢 |

| 法雷尔 |

| 客人 |

| 云顶 |

回答:

select distinct surname

from cd . members

order by surname

limit 10 ; 这里有三个新概念,但是它们都很简单。

SELECT后指定DISTINCT之后的不同之后,将从结果集中删除重复行。请注意,这适用于行:如果行A具有多个列,则仅在所有列中的值相同时,行B仅等于它。一般而言,不要以威利·尼利(Willy-nilly)的方式使用DISTINCT方式 - 从大查询结果集中删除重复项并不是免费的,因此请尽一切努力。ORDER BY (在查询末尾的从FROM和WHERE之后)指定顺序,允许通过列或一组列(逗号分隔)订购结果。LIMIT关键字允许您限制检索到的结果数。这对于一次获得结果很有用,并且可以与OFFSET关键字结合使用以获取以下页面。这与MySQL使用的方法相同,并且非常方便 - 不幸的是,您可能会发现此过程在其他DB中更为复杂。由于某种原因,您想要所有姓氏和所有设施名称的列表。是的,这是一个人为的例子:-)。生产该清单!

预期结果:

| 姓 |

|---|

| 网球场2 |

| Worthington-Smyth |

| 羽毛球法院 |

| 平克 |

| 敢 |

| 坏人 |

| 麦肯齐 |

| 碎屑 |

| 按摩室1 |

| 壁球场 |

回答:

select surname

from cd . members

union

select name

from cd . facilities ; UNION操作员会做您可能期望的事情:将两个SQL查询的结果结合到一个表中。需要注意的是,这两个查询的两个结果都必须具有相同数量的列和兼容数据类型。

UNION删除了重复的行,而UNION ALL没有。默认情况下,请使用UNION ALL使用,除非您关心重复的结果。

您想获得最后会员的注册日期。您如何检索此信息?

预期结果:

| 最新的 |

|---|

| 2012-09-26 18:08:45 |

回答:

select max (joindate) as latest

from cd . members ; 这是我们第一次涉足SQL的汇总功能。它们用于提取有关整个行的信息,并让我们轻松提出类似的问题:

这里的最大聚合函数非常简单:它接收加入的所有可能值,并输出最大的值。汇总功能还有更多的功能,您将在以后的练习中遇到。

您想获得注册的最后一个成员的名字和姓氏,而不仅仅是日期。你怎么做?

预期结果:

| 名 | 姓 | 加入 |

|---|---|---|

| 达伦 | 史密斯 | 2012-09-26 18:08:45 |

回答:

select firstname, surname, joindate

from cd . members

where joindate =

( select max (joindate)

from cd . members ); 在上面建议的方法中,您使用子查询来找出最近的结合。此子查询返回标量表 - 即,一个带有单列和一行的表。由于我们只有一个值,因此我们可以在可能放置一个恒定值的任何地方替换子查询。在这种情况下,我们使用它来完成查询的WHERE子句以找到给定的成员。

您可能希望您能够做以下类似的事情:

select firstname, surname, max (joindate)

from cd . members不幸的是,这无效。 MAX函数不会像WHERE所做的那样限制行 - 它只是占用一大堆值并返回最大的值。然后留下数据库,想知道如何将一长串名称列表与最大功能出现的单个加入日期配对,并且失败。取而代之的是,您不得不说“找到我的行,该行的加入日期与最大联盟日期相同”。

如提示所述,还有其他方法可以完成这项工作 - 下面是一个示例。在这种方法中,我们只需明确地找出最后一个加入日期是什么,而是只需以降序的加入日期订购我们的会员表,然后挑选第一个。请注意,这种方法并不能涵盖两个人同时加入的极端情况:-)。

select firstname, surname, joindate

from cd . members

order by joindate desc

limit 1 ;此类别主要涉及关系数据库系统中的基础概念:加入。加入使您可以组合来自多个表的相关信息来回答问题。这不仅有利于查询:缺乏联接功能会鼓励数据划定数据,这增加了保持数据内部一致的复杂性。

该主题涵盖了内部,外部和自我连接,并花了一点时间在子查询上(查询中的查询)。如果您在这些问题上挣扎,我强烈建议Alan Beaulieu撰写的SQL,作为一本关于该主题的简洁而精心编写的书。

您如何制定名为“ David Farrell”的成员预订的开始列表?

预期结果:

| 开始时间 |

|---|

| 2012-09-18 09:00:00 |

| 2012-09-18 17:30:00 |

| 2012-09-18 13:30:00 |

| 2012-09-18 20:00:00 |

| 2012-09-19 09:30:00 |

| 2012-09-19 15:00:00 |

| 2012-09-19 12:00:00 |

| 2012-09-20 15:30:00 |

| 2012-09-20 11:30:00 |

| 2012-09-20 14:00:00 |

回答:

select bks . starttime

from

cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . members mems

on mems . memid = bks . memid

where

mems . firstname = ' David '

and mems . surname = ' Farrell ' ; 最常用的类型的联接是INNER JOIN 。这样做的方法是根据联接表达式组合两个表 - 在这种情况下,对于成员表中的每个成员ID,我们正在寻找预订表中的匹配值。在我们找到匹配的地方,返回了一个组合每个表的值的行。请注意,我们为每个表提供了一个别名(BKS和MEMS)。这是有两个原因的:首先,它很方便,其次,我们可能会多次加入同一表,要求我们将列与每个不同时间连接的不同时间区分。

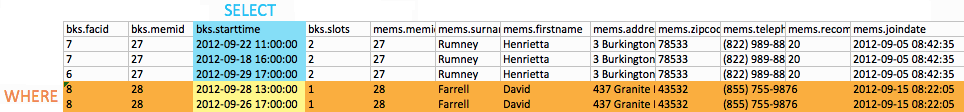

让我们忽略我们的选择和现在的条款,而要关注FROM语句的产生的内容。在我们以前的所有示例中, FROM只是一个简单的表。现在是什么?另一个桌子!这次,它是作为预订和成员组成的。您可以看到下面的加入的输出的子集:

对于成员表中的每个成员,JOIN在预订表中找到了所有匹配的成员ID。对于每场比赛,然后制作了一排从成员表组合行,以及预订表中的行。

显然,这本身就是太多的信息,任何有用的问题都希望将其过滤。在我们的查询中,我们使用SELECT子句的开始来选择列,以及选择行的WHERE子句,如下所示:

这就是我们需要找到大卫预订的全部!通常,我鼓励您记住,从FROM的输出本质上是一张大表格,然后您将信息过滤掉。这听起来可能效率低下 - 但不用担心,在封面下,数据库的行为会更加聪明:-)。

最后一个注意:内在连接有两个不同的语法。我向您展示了我喜欢的那个,发现与其他联接类型更一致。您通常会看到不同的语法,如下所示:

select bks . starttime

from

cd . bookings bks,

cd . members mems

where

mems . firstname = ' David '

and mems . surname = ' Farrell '

and mems . memid = bks . memid ;这在功能上与批准的答案完全相同。如果您对此语法更舒适,请随时使用它!

您如何在“ 2012-09-21”日期为网球场预订的开始时间列表?返回按时间订购的开始时间和设施配对的列表。

预期结果:

| 开始 | 姓名 |

|---|---|

| 2012-09-21 08:00:00 | 网球场1 |

| 2012-09-21 08:00:00 | 网球场2 |

| 2012-09-21 09:30:00 | 网球场1 |

| 2012-09-21 10:00:00 | 网球场2 |

| 2012-09-21 11:30:00 | 网球场2 |

| 2012-09-21 12:00:00 | 网球场1 |

| 2012-09-21 13:30:00 | 网球场1 |

| 2012-09-21 14:00:00 | 网球场2 |

| 2012-09-21 15:30:00 | 网球场1 |

| 2012-09-21 16:00:00 | 网球场2 |

| 2012-09-21 17:00:00 | 网球场1 |

| 2012-09-21 18:00:00 | 网球场2 |

回答:

select bks . starttime as start, facs . name as name

from

cd . facilities facs

inner join cd . bookings bks

on facs . facid = bks . facid

where

facs . facid in ( 0 , 1 ) and

bks . starttime >= ' 2012-09-21 ' and

bks . starttime < ' 2012-09-22 '

order by bks . starttime ; 这是另一个INNER JOIN查询,尽管它的复杂性更加复杂!查询的FROM很容易 - 我们只是将设施和预订表加在一起。这会产生一张表格,对于预订中的每一行,我们都附加了有关预订设施的详细信息。

到查询的WHERE组件。对开始时间的检查是相当自我解释的 - 我们确保所有预订都在指定的日期之间开始。由于我们只对网球场感兴趣,因此我们还使用IN运营商告诉数据库系统,仅向我们提供回式设施IDS 0或1-法院的IDS。还有其他方法可以表达出来:我们可以where facs.facid = 0 or facs.facid = 1使用,甚至where facs.name like 'Tennis%' 。

其余的非常简单:我们SELECT我们感兴趣的列,然后在开始时间ORDER BY 。

您如何输出所有推荐其他成员的成员的列表?确保列表中没有重复项,并且结果由(姓氏,firstName)订购。

预期结果:

| 名 | 姓 |

|---|---|

| 佛罗伦萨 | 坏人 |

| 蒂莫西 | 贝克 |

| 杰拉尔德 | 黄油 |

| 杰米玛 | 法雷尔 |

| 马修 | 云顶 |

| 大卫 | 琼斯 |

| 珍妮丝 | 乔普特 |

| 米里森 | 范围 |

| 蒂姆 | 罗恩南 |

| 达伦 | 史密斯 |

| 特雷西 | 史密斯 |

| 思考 | Stibbons |

| 伯顿 | 特雷西 |

回答:

select distinct recs . firstname as firstname, recs . surname as surname

from

cd . members mems

inner join cd . members recs

on recs . memid = mems . recommendedby

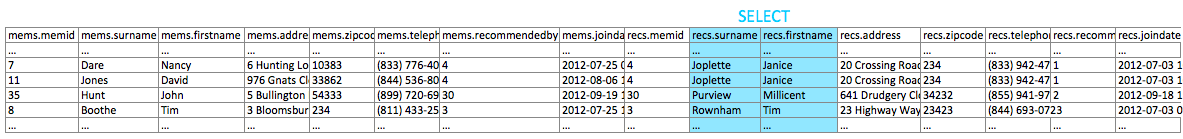

order by surname, firstname; 这是一些人感到困惑的概念:您可以加入桌子!如果您在同一表中具有参考数据的列,就像我们在cd.members中使用的推荐一样,这真的很有用。

如果您难以实现此目标,请记住,这与任何其他内部联接一样。我们的加入将每行都带入具有推荐值的成员中,并再次查找具有匹配成员ID的行。然后,它生成一个组合两个成员条目的输出行。这看起来像以下图:

请注意,尽管我们可能在输出集中有两个“姓氏”列,但它们可以通过其表格别名区分。一旦选择了所需的列,我们就简单地使用DISTINCT来确保没有重复。

您如何输出所有成员的列表,包括推荐他们的个人(如果有)?确保结果由(姓氏,名称)订购。

预期结果:

| memfname | memsname | recFname | recsname |

|---|---|---|---|

| 佛罗伦萨 | 坏人 | 思考 | Stibbons |

| 安妮 | 贝克 | 思考 | Stibbons |

| 蒂莫西 | 贝克 | 杰米玛 | 法雷尔 |

| 蒂姆 | 展位 | 蒂姆 | 罗恩南 |

| 杰拉尔德 | 黄油 | 达伦 | 史密斯 |

| 琼 | 科普林 | 蒂莫西 | 贝克 |

| 埃里卡 | 碎屑 | 特雷西 | 史密斯 |

| 南希 | 敢 | 珍妮丝 | 乔普特 |

| 大卫 | 法雷尔 | ||

| 杰米玛 | 法雷尔 | ||

| 客人 | 客人 | ||

| 马修 | 云顶 | 杰拉尔德 | 黄油 |

| 约翰 | 打猎 | 米里森 | 范围 |

| 大卫 | 琼斯 | 珍妮丝 | 乔普特 |

| 道格拉斯 | 琼斯 | 大卫 | 琼斯 |

| 珍妮丝 | 乔普特 | 达伦 | 史密斯 |

| 安娜 | 麦肯齐 | 达伦 | 史密斯 |

| 查尔斯 | 欧文 | 达伦 | 史密斯 |

| 大卫 | 平克 | 杰米玛 | 法雷尔 |

| 米里森 | 范围 | 特雷西 | 史密斯 |

| 蒂姆 | 罗恩南 | ||

| 亨利埃塔 | 拉姆尼 | 马修 | 云顶 |

| 拉姆纳雷什 | 萨尔文 | 佛罗伦萨 | 坏人 |

| 达伦 | 史密斯 | ||

| 达伦 | 史密斯 | ||

| 杰克 | 史密斯 | 达伦 | 史密斯 |

| 特雷西 | 史密斯 | ||

| 思考 | Stibbons | 伯顿 | 特雷西 |

| 伯顿 | 特雷西 | ||

| 风信子 | 特百惠 | ||

| 亨利 | Worthington-Smyth | 特雷西 | 史密斯 |

回答:

select mems . firstname as memfname, mems . surname as memsname, recs . firstname as recfname, recs . surname as recsname

from

cd . members mems

left outer join cd . members recs

on recs . memid = mems . recommendedby

order by memsname, memfname; 让我们介绍另一个新概念: LEFT OUTER JOIN 。最好通过它们与内在的连接不同的方式来解释这些。内部连接左右桌子,并根据联接条件( ON )寻找匹配行。满足条件后,会产生一个连接的行。 LEFT OUTER JOIN运行方式类似,只是,如果左侧表上的一个给定行与任何内容都不匹配,则仍然会产生输出行。该输出行由左手表行组成,并代替右手表行的一堆NULLS 。

在这样的情况下,这很有用,我们想在其中产生带有可选数据的输出。我们想要所有成员的名字,以及如果该人的存在的名称。您无法通过内在联接正确表达这一点。

您可能已经猜到了,还有其他外部连接。 RIGHT OUTER JOIN非常类似于LEFT OUTER JOIN ,只是表达式的左侧是包含可选数据的表达式。很少使用的FULL OUTER JOIN将表达式的两侧视为可选的。

您如何找到使用网球场的所有成员的清单?在您的输出中包括法院的名称,以及以单列格式的成员名称。确保没有重复的数据,并按成员名称订购。

预期结果:

| 成员 | 设施 |

|---|---|

| 安妮·贝克 | 网球场2 |

| 安妮·贝克 | 网球场1 |

| 伯顿·特雷西 | 网球场2 |

| 伯顿·特雷西 | 网球场1 |

| 查尔斯·欧文 | 网球场2 |

| 查尔斯·欧文 | 网球场1 |

| 达伦·史密斯(Darren Smith) | 网球场2 |

| 大卫·法雷尔(David Farrell) | 网球场2 |

| 大卫·法雷尔(David Farrell) | 网球场1 |

| 大卫·琼斯 | 网球场1 |

| 大卫·琼斯 | 网球场2 |

| 大卫·平克(David Pinker) | 网球场1 |

| 道格拉斯·琼斯(Douglas Jones) | 网球场1 |

| Erica Crumpet | 网球场1 |

| 佛罗伦萨·巴德 | 网球场1 |

| 佛罗伦萨·巴德 | 网球场2 |

| 来宾 | 网球场2 |

| 来宾 | 网球场1 |

| 杰拉尔德·巴特斯(Gerald Butters) | 网球场1 |

| 杰拉尔德·巴特斯(Gerald Butters) | 网球场2 |

| Henrietta Rumney | 网球场2 |

| 杰克·史密斯 | 网球场1 |

| 杰克·史密斯 | 网球场2 |

| 珍妮丝·乔普莱特(Janice Joplette) | 网球场1 |

| 珍妮丝·乔普莱特(Janice Joplette) | 网球场2 |

| 杰米玛·法雷尔(Jemima Farrell) | 网球场2 |

| 杰米玛·法雷尔(Jemima Farrell) | 网球场1 |

| 琼·科普林 | 网球场1 |

| 约翰·亨特 | 网球场1 |

| 约翰·亨特 | 网球场2 |

| 马修·云顶 | 网球场1 |

| Millicent Purview | 网球场2 |

| 南希·敢 | 网球场2 |

| 南希·敢 | 网球场1 |

| 思考史蒂布斯 | 网球场2 |

| 思考史蒂布斯 | 网球场1 |

| Ramnaresh Sarwin | 网球场2 |

| Ramnaresh Sarwin | 网球场1 |

| 蒂姆·布特 | 网球场1 |

| 蒂姆·布特 | 网球场2 |

| 蒂姆·罗恩纳姆(Tim Rownam) | 网球场1 |

| 蒂姆·罗恩纳姆(Tim Rownam) | 网球场2 |

| 蒂莫西·贝克(Timothy Baker) | 网球场2 |

| 蒂莫西·贝克(Timothy Baker) | 网球场1 |

| 特雷西·史密斯 | 网球场2 |

| 特雷西·史密斯 | 网球场1 |

回答:

select distinct mems . firstname || ' ' || mems . surname as member, facs . name as facility

from

cd . members mems

inner join cd . bookings bks

on mems . memid = bks . memid

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

where

bks . facid in ( 0 , 1 )

order by member 这项练习在很大程度上是您在先前问题中学到的知识的更为复杂的应用。这也是我们第一次使用多个加入,这可能有些混乱。在阅读加入表达式时,请记住,一个连接是一个有效的函数,该函数占两个表,一个标记为左表,另一个标记为右表。只需在查询中加入一个即可可视化这很容易可视化,但与两个相关。

我们在此查询中的第二个INNER JOIN具有CD.FICISITIONS的右侧。这很容易掌握。但是,左侧是通过将CD.会员加入CD.Bookings返回的桌子。强调这一点很重要:关系模型与表有关。任何加入的输出是另一个表。查询的输出是一个表。单列列表是表。一旦掌握了这一点,就可以掌握模型的基本美。

最后,我们确实在这里介绍了一件新事物: ||操作员用于连接字符串。

您如何在2012-09-14当天制定预订列表,这将使会员(或来宾)损失超过30美元?请记住,客人对成员的费用不同(列出的成本为每半小时的“插槽”),并且来宾用户始终是ID 0。在您的输出中包括设施的名称,成员名称为单一列,以及成本。通过下降成本订购,不要使用任何子征服。

预期结果:

| 成员 | 设施 | 成本 |

|---|---|---|

| 来宾 | 按摩室2 | 320 |

| 来宾 | 按摩室1 | 160 |

| 来宾 | 按摩室1 | 160 |

| 来宾 | 按摩室1 | 160 |

| 来宾 | 网球场2 | 150 |

| 杰米玛·法雷尔(Jemima Farrell) | 按摩室1 | 140 |

| 来宾 | 网球场1 | 75 |

| 来宾 | 网球场2 | 75 |

| 来宾 | 网球场1 | 75 |

| 马修·云顶 | 按摩室1 | 70 |

| 佛罗伦萨·巴德 | 按摩室2 | 70 |

| 来宾 | 壁球场 | 70.0 |

| 杰米玛·法雷尔(Jemima Farrell) | 按摩室1 | 70 |

| 思考史蒂布斯 | 按摩室1 | 70 |

| 伯顿·特雷西 | 按摩室1 | 70 |

| 杰克·史密斯 | 按摩室1 | 70 |

| 来宾 | 壁球场 | 35.0 |

| 来宾 | 壁球场 | 35.0 |

回答:

select mems . firstname || ' ' || mems . surname as member,

facs . name as facility,

case

when mems . memid = 0 then

bks . slots * facs . guestcost

else

bks . slots * facs . membercost

end as cost

from

cd . members mems

inner join cd . bookings bks

on mems . memid = bks . memid

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

where

bks . starttime >= ' 2012-09-14 ' and

bks . starttime < ' 2012-09-15 ' and (

( mems . memid = 0 and bks . slots * facs . guestcost > 30 ) or

( mems . memid != 0 and bks . slots * facs . membercost > 30 )

)

order by cost desc ; 这有点复杂!虽然它比我们以前使用的要复杂的逻辑还要复杂,但并没有很多值得注意的话题。 WHERE子句将我们的产出限制为在2012 - 09-14的足够昂贵的行,记得区分客人和其他人。然后,我们在“选择”列中使用CASE语句为会员或来宾输出正确的成本。

您如何在不使用任何加入的情况下输出所有成员的列表,包括推荐他们的个人(如果有的话)?确保列表中没有重复项,并且每个firstName +姓氏配对都格式化为列并订购。

预期结果:

| 成员 | 推荐人 |

|---|---|

| 安娜·麦肯齐(Anna Mackenzie) | 达伦·史密斯(Darren Smith) |

| 安妮·贝克 | 思考史蒂布斯 |

| 伯顿·特雷西 | |

| 查尔斯·欧文 | 达伦·史密斯(Darren Smith) |

| 达伦·史密斯(Darren Smith) | |

| 大卫·法雷尔(David Farrell) | |

| 大卫·琼斯 | 珍妮丝·乔普莱特(Janice Joplette) |

| 大卫·平克(David Pinker) | 杰米玛·法雷尔(Jemima Farrell) |

| 道格拉斯·琼斯(Douglas Jones) | 大卫·琼斯 |

| Erica Crumpet | 特雷西·史密斯 |

| 佛罗伦萨·巴德 | 思考史蒂布斯 |

| 来宾 | |

| 杰拉尔德·巴特斯(Gerald Butters) | 达伦·史密斯(Darren Smith) |

| Henrietta Rumney | 马修·云顶 |

| 亨利·沃辛顿 - 史密斯 | 特雷西·史密斯 |

| 风信子特百惠 | |

| 杰克·史密斯 | 达伦·史密斯(Darren Smith) |

| 珍妮丝·乔普莱特(Janice Joplette) | 达伦·史密斯(Darren Smith) |

| 杰米玛·法雷尔(Jemima Farrell) | |

| 琼·科普林 | 蒂莫西·贝克(Timothy Baker) |

| 约翰·亨特 | Millicent Purview |

| 马修·云顶 | 杰拉尔德·巴特斯(Gerald Butters) |

| Millicent Purview | 特雷西·史密斯 |

| 南希·敢 | 珍妮丝·乔普莱特(Janice Joplette) |

| 思考史蒂布斯 | 伯顿·特雷西 |

| Ramnaresh Sarwin | 佛罗伦萨·巴德 |

| 蒂姆·布特 | 蒂姆·罗恩纳姆(Tim Rownam) |

| 蒂姆·罗恩纳姆(Tim Rownam) | |

| 蒂莫西·贝克(Timothy Baker) | 杰米玛·法雷尔(Jemima Farrell) |

| 特雷西·史密斯 |

回答:

select distinct mems . firstname || ' ' || mems . surname as member,

( select recs . firstname || ' ' || recs . surname as recommender

from cd . members recs

where recs . memid = mems . recommendedby

)

from

cd . members mems

order by member; 此练习标志着次级的引入。顾名思义,在查询中查询。它们通常与聚集体一起使用,以回答诸如“让我在网球场1中度过最多时间的成员的所有细节”之类的问题。

在这种情况下,我们只是使用子查询模仿外部连接。对于成员的每个值,都会运行一次子查询以找到推荐它们的个人名称(如果有)。 A subquery that uses information from the outer query in this way (and thus has to be run for each row in the result set) is known as a correlated subquery .

The Produce a list of costly bookings exercise contained some messy logic: we had to calculate the booking cost in both the WHERE clause and the CASE statement. Try to simplify this calculation using subqueries. For reference, the question was:

How can you produce a list of bookings on the day of 2012-09-14 which will cost the member (or guest) more than $30? Remember that guests have different costs to members (the listed costs are per half-hour 'slot'), and the guest user is always ID 0. Include in your output the name of the facility, the name of the member formatted as a single column, and the cost. Order by descending cost.

预期结果:

| 成员 | 设施 | 成本 |

|---|---|---|

| GUEST GUEST | Massage Room 2 | 320 |

| GUEST GUEST | Massage Room 1 | 160 |

| GUEST GUEST | Massage Room 1 | 160 |

| GUEST GUEST | Massage Room 1 | 160 |

| GUEST GUEST | Tennis Court 2 | 150 |

| Jemima Farrell | Massage Room 1 | 140 |

| GUEST GUEST | Tennis Court 1 | 75 |

| GUEST GUEST | Tennis Court 2 | 75 |

| GUEST GUEST | Tennis Court 1 | 75 |

| Matthew Genting | Massage Room 1 | 70 |

| Florence Bader | Massage Room 2 | 70 |

| GUEST GUEST | Squash Court | 70.0 |

| Jemima Farrell | Massage Room 1 | 70 |

| Ponder Stibbons | Massage Room 1 | 70 |

| Burton Tracy | Massage Room 1 | 70 |

| 杰克·史密斯 | Massage Room 1 | 70 |

| GUEST GUEST | Squash Court | 35.0 |

| GUEST GUEST | Squash Court | 35.0 |

回答:

select member, facility, cost from (

select

mems . firstname || ' ' || mems . surname as member,

facs . name as facility,

case

when mems . memid = 0 then

bks . slots * facs . guestcost

else

bks . slots * facs . membercost

end as cost

from

cd . members mems

inner join cd . bookings bks

on mems . memid = bks . memid

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

where

bks . starttime >= ' 2012-09-14 ' and

bks . starttime < ' 2012-09-15 '

) as bookings

where cost > 30

order by cost desc ; This answer provides a mild simplification to the previous iteration: in the no-subquery version, we had to calculate the member or guest's cost in both the WHERE clause and the CASE statement. In our new version, we produce an inline query that calculates the total booking cost for us, allowing the outer query to simply select the bookings it's looking for. For reference, you may also see subqueries in the FROM clause referred to as inline views .

Querying data is all well and good, but at some point you're probably going to want to put data into your database! This section deals with inserting, updating, and deleting information. Operations that alter your data like this are collectively known as Data Manipulation Language, or DML.

In previous sections, we returned to you the results of the query you've performed. Since modifications like the ones we're making in this section don't return any query results, we instead show you the updated content of the table you're supposed to be working on. You can compare this with the table shown in 'Expected Results' to see how you've done.

If you struggle with these questions, I strongly recommend Learning SQL, by Alan Beaulieu.

The club is adding a new facility - a spa. We need to add it into the facilities table. Use the following values:

预期结果:

| facid | 姓名 | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | 乒乓球 | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Pool Table | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

| 9 | 温泉 | 20 | 30 | 100000 | 800 |

回答:

insert into cd . facilities

(facid, name, membercost, guestcost, initialoutlay, monthlymaintenance)

values ( 9 , ' Spa ' , 20 , 30 , 100000 , 800 ); INSERT INTO ... VALUES is the simplest way to insert data into a table. There's not a whole lot to discuss here: VALUES is used to construct a row of data, which the INSERT statement inserts into the table. It's a simple as that.

You can see that there's two sections in parentheses. The first is part of the INSERT statement, and specifies the columns that we're providing data for. The second is part of VALUES , and specifies the actual data we want to insert into each column.

If we're inserting data into every column of the table, as in this example, explicitly specifying the column names is optional. As long as you fill in data for all columns of the table, in the order they were defined when you created the table, you can do something like the following:

insert into cd . facilities values ( 9 , ' Spa ' , 20 , 30 , 100000 , 800 );Generally speaking, for SQL that's going to be reused I tend to prefer being explicit and specifying the column names.

In the previous exercise, you learned how to add a facility. Now you're going to add multiple facilities in one command. Use the following values:

预期结果:

| facid | 姓名 | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | 乒乓球 | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Pool Table | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

| 9 | 温泉 | 20 | 30 | 100000 | 800 |

| 10 | Squash Court 2 | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

回答:

insert into cd . facilities

(facid, name, membercost, guestcost, initialoutlay, monthlymaintenance)

values

( 9 , ' Spa ' , 20 , 30 , 100000 , 800 ),

( 10 , ' Squash Court 2 ' , 3 . 5 , 17 . 5 , 5000 , 80 ); VALUES can be used to generate more than one row to insert into a table, as seen in this example. Hopefully it's clear what's going on here: the output of VALUES is a table, and that table is copied into cd.facilities, the table specified in the INSERT command.

While you'll most commonly see VALUES when inserting data, Postgres allows you to use VALUES wherever you might use a SELECT . This makes sense: the output of both commands is a table, it's just that VALUES is a bit more ergonomic when working with constant data.

Similarly, it's possible to use SELECT wherever you see a VALUES . This means that you can INSERT the results of a SELECT .例如:

insert into cd . facilities

(facid, name, membercost, guestcost, initialoutlay, monthlymaintenance)

SELECT 9 , ' Spa ' , 20 , 30 , 100000 , 800

UNION ALL

SELECT 10 , ' Squash Court 2 ' , 3 . 5 , 17 . 5 , 5000 , 80 ; In later exercises you'll see us using INSERT ... SELECT to generate data to insert based on the information already in the database.

Let's try adding the spa to the facilities table again. This time, though, we want to automatically generate the value for the next facid, rather than specifying it as a constant. Use the following values for everything else:

预期结果:

| facid | 姓名 | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | 乒乓球 | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Pool Table | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

| 9 | 温泉 | 20 | 30 | 100000 | 800 |

回答:

insert into cd . facilities

(facid, name, membercost, guestcost, initialoutlay, monthlymaintenance)

select ( select max (facid) from cd . facilities ) + 1 , ' Spa ' , 20 , 30 , 100000 , 800 ; In the previous exercises we used VALUES to insert constant data into the facilities table. Here, though, we have a new requirement: a dynamically generated ID. This gives us a real quality of life improvement, as we don't have to manually work out what the current largest ID is: the SQL command does it for us.

Since the VALUES clause is only used to supply constant data, we need to replace it with a query instead. The SELECT statement is fairly simple: there's an inner subquery that works out the next facid based on the largest current id, and the rest is just constant data. The output of the statement is a row that we insert into the facilities table.

While this works fine in our simple example, it's not how you would generally implement an incrementing ID in the real world. Postgres provides SERIAL types that are auto-filled with the next ID when you insert a row. As well as saving us effort, these types are also safer: unlike the answer given in this exercise, there's no need to worry about concurrent operations generating the same ID.

We made a mistake when entering the data for the second tennis court. The initial outlay was 10000 rather than 8000: you need to alter the data to fix the error.

预期结果:

| facid | 姓名 | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | 乒乓球 | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Pool Table | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

回答:

update cd . facilities

set initialoutlay = 10000

where facid = 1 ; The UPDATE statement is used to alter existing data. If you're familiar with SELECT queries, it's pretty easy to read: the WHERE clause works in exactly the same fashion, allowing us to filter the set of rows we want to work with. These rows are then modified according to the specifications of the SET clause: in this case, setting the initial outlay.

The WHERE clause is extremely important. It's easy to get it wrong or even omit it, with disastrous results. Consider the following command:

update cd . facilities

set initialoutlay = 10000 ; There's no WHERE clause to filter for the rows we're interested in. The result of this is that the update runs on every row in the table! This is rarely what we want to happen.

We want to increase the price of the tennis courts for both members and guests. Update the costs to be 6 for members, and 30 for guests.

| facid | 姓名 | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 6 | 30 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 6 | 30 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | 乒乓球 | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Pool Table | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

回答:

update cd . facilities

set

membercost = 6 ,

guestcost = 30

where facid in ( 0 , 1 ); The SET clause accepts a comma separated list of values that you want to update.

We want to alter the price of the second tennis court so that it costs 10% more than the first one. Try to do this without using constant values for the prices, so that we can reuse the statement if we want to.

预期结果:

| facid | 姓名 | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 5.5 | 27.5 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | 乒乓球 | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Pool Table | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

回答:

update cd . facilities facs

set

membercost = ( select membercost * 1 . 1 from cd . facilities where facid = 0 ),

guestcost = ( select guestcost * 1 . 1 from cd . facilities where facid = 0 )

where facs . facid = 1 ; Updating columns based on calculated data is not too intrinsically difficult: we can do so pretty easily using subqueries. You can see this approach in our selected answer.

As the number of columns we want to update increases, standard SQL can start to get pretty awkward: you don't want to be specifying a separate subquery for each of 15 different column updates. Postgres provides a nonstandard extension to SQL called UPDATE...FROM that addresses this: it allows you to supply a FROM clause to generate values for use in the SET clause. Example below:

update cd . facilities facs

set

membercost = facs2 . membercost * 1 . 1 ,

guestcost = facs2 . guestcost * 1 . 1

from ( select * from cd . facilities where facid = 0 ) facs2

where facs . facid = 1 ;As part of a clearout of our database, we want to delete all bookings from the cd.bookings table. How can we accomplish this?

预期结果:

| bookid | facid | memid | starttime | 老虎机 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

回答:

delete from cd . bookings ; The DELETE statement does what it says on the tin: deletes rows from the table. Here, we show the command in its simplest form, with no qualifiers. In this case, it deletes everything from the table. Obviously, you should be careful with your deletes and make sure they're always limited - we'll see how to do that in the next exercise.

An alternative to unqualified DELETE s is the following:

truncate cd . bookings ; TRUNCATE also deletes everything in the table, but does so using a quicker underlying mechanism. It's not perfectly safe in all circumstances, though, so use judiciously. When in doubt, use DELETE .

We want to remove member 37, who has never made a booking, from our database. How can we achieve that?

预期结果:

| memid | 姓 | 名 | 地址 | 邮政编码 | 电话 | recommendedby | joindate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 客人 | 客人 | 客人 | 0 | (000)000-0000 | 2012-07-01 00:00:00 | |

| 1 | 史密斯 | 达伦 | 8 Bloomsbury Close, Boston | 4321 | 555-555-5555 | 2012-07-02 12:02:05 | |

| 2 | 史密斯 | 特雷西 | 8 Bloomsbury Close, New York | 4321 | 555-555-5555 | 2012-07-02 12:08:23 | |

| 3 | Rownam | 蒂姆 | 23 Highway Way, Boston | 23423 | (844) 693-0723 | 2012-07-03 09:32:15 | |

| 4 | Joplette | 珍妮丝 | 20 Crossing Road, New York | 234 | (833) 942-4710 | 1 | 2012-07-03 10:25:05 |

| 5 | Butters | 杰拉尔德 | 1065 Huntingdon Avenue, Boston | 56754 | (844) 078-4130 | 1 | 2012-07-09 10:44:09 |

| 6 | 特雷西 | 伯顿 | 3 Tunisia Drive, Boston | 45678 | (822) 354-9973 | 2012-07-15 08:52:55 | |

| 7 | 敢 | 南希 | 6 Hunting Lodge Way, Boston | 10383 | (833) 776-4001 | 4 | 2012-07-25 08:59:12 |

| 8 | Boothe | 蒂姆 | 3 Bloomsbury Close, Reading, 00234 | 234 | (811) 433-2547 | 3 | 2012-07-25 16:02:35 |

| 9 | Stibbons | 思考 | 5 Dragons Way, Winchester | 87630 | (833) 160-3900 | 6 | 2012-07-25 17:09:05 |

| 10 | 欧文 | 查尔斯 | 52 Cheshire Grove, Winchester, 28563 | 28563 | (855) 542-5251 | 1 | 2012-08-03 19:42:37 |

| 11 | 琼斯 | 大卫 | 976 Gnats Close, Reading | 33862 | (844) 536-8036 | 4 | 2012-08-06 16:32:55 |

| 12 | 贝克 | 安妮 | 55 Powdery Street, Boston | 80743 | 844-076-5141 | 9 | 2012-08-10 14:23:22 |

| 13 | Farrell | Jemima | 103 Firth Avenue, North Reading | 57392 | (855) 016-0163 | 2012-08-10 14:28:01 | |

| 14 | 史密斯 | 杰克 | 252 Binkington Way, Boston | 69302 | (822) 163-3254 | 1 | 2012-08-10 16:22:05 |

| 15 | 坏人 | 佛罗伦萨 | 264 Ursula Drive, Westford | 84923 | (833) 499-3527 | 9 | 2012-08-10 17:52:03 |

| 16 | 贝克 | 蒂莫西 | 329 James Street, Reading | 58393 | 833-941-0824 | 13 | 2012-08-15 10:34:25 |

| 17 | Pinker | 大卫 | 5 Impreza Road, Boston | 65332 | 811 409-6734 | 13 | 2012-08-16 11:32:47 |

| 20 | Genting | 马修 | 4 Nunnington Place, Wingfield, Boston | 52365 | (811) 972-1377 | 5 | 2012-08-19 14:55:55 |

| 21 | 麦肯齐 | 安娜 | 64 Perkington Lane, Reading | 64577 | (822) 661-2898 | 1 | 2012-08-26 09:32:05 |

| 22 | Coplin | 琼 | 85 Bard Street, Bloomington, Boston | 43533 | (822) 499-2232 | 16 | 2012-08-29 08:32:41 |

| 24 | Sarwin | Ramnaresh | 12 Bullington Lane, Boston | 65464 | (822) 413-1470 | 15 | 2012-09-01 08:44:42 |

| 26 | 琼斯 | 道格拉斯 | 976 Gnats Close, Reading | 11986 | 844 536-8036 | 11 | 2012-09-02 18:43:05 |

| 27 | Rumney | 亨利埃塔 | 3 Burkington Plaza, Boston | 78533 | (822) 989-8876 | 20 | 2012-09-05 08:42:35 |

| 28 | Farrell | 大卫 | 437 Granite Farm Road, Westford | 43532 | (855) 755-9876 | 2012-09-15 08:22:05 | |

| 29 | Worthington-Smyth | 亨利 | 55 Jagbi Way, North Reading | 97676 | (855) 894-3758 | 2 | 2012-09-17 12:27:15 |

| 30 | 范围 | Millicent | 641 Drudgery Close, Burnington, Boston | 34232 | (855) 941-9786 | 2 | 2012-09-18 19:04:01 |

| 33 | 特百惠 | 风信子 | 33 Cheerful Plaza, Drake Road, Westford | 68666 | (822) 665-5327 | 2012-09-18 19:32:05 | |

| 35 | 打猎 | 约翰 | 5 Bullington Lane, Boston | 54333 | (899) 720-6978 | 30 | 2012-09-19 11:32:45 |

| 36 | Crumpet | 埃里卡 | Crimson Road, North Reading | 75655 | (811) 732-4816 | 2 | 2012-09-22 08:36:38 |

回答:

delete from cd . members where memid = 37 ; This exercise is a small increment on our previous one. Instead of deleting all bookings, this time we want to be a bit more targeted, and delete a single member that has never made a booking. To do this, we simply have to add a WHERE clause to our command, specifying the member we want to delete. You can see the parallels with SELECT and UPDATE statements here.

There's one interesting wrinkle here. Try this command out, but substituting in member id 0 instead. This member has made many bookings, and you'll find that the delete fails with an error about a foreign key constraint violation. This is an important concept in relational databases, so let's explore a little further.

Foreign keys are a mechanism for defining relationships between columns of different tables. In our case we use them to specify that the memid column of the bookings table is related to the memid column of the members table. The relationship (or 'constraint') specifies that for a given booking, the member specified in the booking must exist in the members table. It's useful to have this guarantee enforced by the database: it means that code using the database can rely on the presence of the member. It's hard (even impossible) to enforce this at higher levels: concurrent operations can interfere and leave your database in a broken state.

PostgreSQL supports various different kinds of constraints that allow you to enforce structure upon your data. For more information on constraints, check out the PostgreSQL documentation on foreign keys

In our previous exercises, we deleted a specific member who had never made a booking. How can we make that more general, to delete all members who have never made a booking?

预期结果:

| memid | 姓 | 名 | 地址 | 邮政编码 | 电话 | recommendedby | joindate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 客人 | 客人 | 客人 | 0 | (000)000-0000 | 2012-07-01 00:00:00 | |

| 1 | 史密斯 | 达伦 | 8 Bloomsbury Close, Boston | 4321 | 555-555-5555 | 2012-07-02 12:02:05 | |

| 2 | 史密斯 | 特雷西 | 8 Bloomsbury Close, New York | 4321 | 555-555-5555 | 2012-07-02 12:08:23 | |

| 3 | Rownam | 蒂姆 | 23 Highway Way, Boston | 23423 | (844) 693-0723 | 2012-07-03 09:32:15 | |

| 4 | Joplette | 珍妮丝 | 20 Crossing Road, New York | 234 | (833) 942-4710 | 1 | 2012-07-03 10:25:05 |

| 5 | Butters | 杰拉尔德 | 1065 Huntingdon Avenue, Boston | 56754 | (844) 078-4130 | 1 | 2012-07-09 10:44:09 |

| 6 | 特雷西 | 伯顿 | 3 Tunisia Drive, Boston | 45678 | (822) 354-9973 | 2012-07-15 08:52:55 | |

| 7 | 敢 | 南希 | 6 Hunting Lodge Way, Boston | 10383 | (833) 776-4001 | 4 | 2012-07-25 08:59:12 |

| 8 | Boothe | 蒂姆 | 3 Bloomsbury Close, Reading, 00234 | 234 | (811) 433-2547 | 3 | 2012-07-25 16:02:35 |

| 9 | Stibbons | 思考 | 5 Dragons Way, Winchester | 87630 | (833) 160-3900 | 6 | 2012-07-25 17:09:05 |

| 10 | 欧文 | 查尔斯 | 52 Cheshire Grove, Winchester, 28563 | 28563 | (855) 542-5251 | 1 | 2012-08-03 19:42:37 |

| 11 | 琼斯 | 大卫 | 976 Gnats Close, Reading | 33862 | (844) 536-8036 | 4 | 2012-08-06 16:32:55 |

| 12 | 贝克 | 安妮 | 55 Powdery Street, Boston | 80743 | 844-076-5141 | 9 | 2012-08-10 14:23:22 |

| 13 | Farrell | Jemima | 103 Firth Avenue, North Reading | 57392 | (855) 016-0163 | 2012-08-10 14:28:01 | |

| 14 | 史密斯 | 杰克 | 252 Binkington Way, Boston | 69302 | (822) 163-3254 | 1 | 2012-08-10 16:22:05 |

| 15 | 坏人 | 佛罗伦萨 | 264 Ursula Drive, Westford | 84923 | (833) 499-3527 | 9 | 2012-08-10 17:52:03 |

| 16 | 贝克 | 蒂莫西 | 329 James Street, Reading | 58393 | 833-941-0824 | 13 | 2012-08-15 10:34:25 |

| 17 | Pinker | 大卫 | 5 Impreza Road, Boston | 65332 | 811 409-6734 | 13 | 2012-08-16 11:32:47 |

| 20 | Genting | 马修 | 4 Nunnington Place, Wingfield, Boston | 52365 | (811) 972-1377 | 5 | 2012-08-19 14:55:55 |

| 21 | 麦肯齐 | 安娜 | 64 Perkington Lane, Reading | 64577 | (822) 661-2898 | 1 | 2012-08-26 09:32:05 |

| 22 | Coplin | 琼 | 85 Bard Street, Bloomington, Boston | 43533 | (822) 499-2232 | 16 | 2012-08-29 08:32:41 |

| 24 | Sarwin | Ramnaresh | 12 Bullington Lane, Boston | 65464 | (822) 413-1470 | 15 | 2012-09-01 08:44:42 |

| 26 | 琼斯 | 道格拉斯 | 976 Gnats Close, Reading | 11986 | 844 536-8036 | 11 | 2012-09-02 18:43:05 |

| 27 | Rumney | 亨利埃塔 | 3 Burkington Plaza, Boston | 78533 | (822) 989-8876 | 20 | 2012-09-05 08:42:35 |

| 28 | Farrell | 大卫 | 437 Granite Farm Road, Westford | 43532 | (855) 755-9876 | 2012-09-15 08:22:05 | |

| 29 | Worthington-Smyth | 亨利 | 55 Jagbi Way, North Reading | 97676 | (855) 894-3758 | 2 | 2012-09-17 12:27:15 |

| 30 | 范围 | Millicent | 641 Drudgery Close, Burnington, Boston | 34232 | (855) 941-9786 | 2 | 2012-09-18 19:04:01 |

| 33 | 特百惠 | 风信子 | 33 Cheerful Plaza, Drake Road, Westford | 68666 | (822) 665-5327 | 2012-09-18 19:32:05 | |

| 35 | 打猎 | 约翰 | 5 Bullington Lane, Boston | 54333 | (899) 720-6978 | 30 | 2012-09-19 11:32:45 |

| 36 | Crumpet | 埃里卡 | Crimson Road, North Reading | 75655 | (811) 732-4816 | 2 | 2012-09-22 08:36:38 |

回答:

delete from cd . members where memid not in ( select memid from cd . bookings ); We can use subqueries to determine whether a row should be deleted or not. There's a couple of standard ways to do this. In our featured answer, the subquery produces a list of all the different member ids in the cd.bookings table. If a row in the table isn't in the list generated by the subquery, it gets deleted.

An alternative is to use a correlated subquery . Where our previous example runs a large subquery once, the correlated approach instead specifies a smaller subqueryto run against every row.

delete from cd . members mems where not exists ( select 1 from cd . bookings where memid = mems . memid );The two different forms can have different performance characteristics. Under the hood, your database engine is free to transform your query to execute it in a correlated or uncorrelated fashion, though, so things can be a little hard to predict.

Aggregation is one of those capabilities that really make you appreciate the power of relational database systems. It allows you to move beyond merely persisting your data, into the realm of asking truly interesting questions that can be used to inform decision making. This category covers aggregation at length, making use of standard grouping as well as more recent window functions.

If you struggle with these questions, I strongly recommend Learning SQL, by Alan Beaulieu and SQL Cookbook by Anthony Molinaro. In fact, get the latter anyway - it'll take you beyond anything you find on this site, and on multiple different database systems to boot.

For our first foray into aggregates, we're going to stick to something simple. We want to know how many facilities exist - simply produce a total count.

预期结果:

| 数数 |

|---|

| 9 |

回答:

select count ( * ) from cd . facilities ; Aggregation starts out pretty simply! The SQL above selects everything from our facilities table, and then counts the number of rows in the result set. The count function has a variety of uses:

COUNT(*) simply returns the number of rowsCOUNT(address) counts the number of non-null addresses in the result set.COUNT(DISTINCT address) counts the number of different addresses in the facilities table. The basic idea of an aggregate function is that it takes in a column of data, performs some function upon it, and outputs a scalar (single) value. There are a bunch more aggregation functions, including MAX , MIN , SUM , and AVG . These all do pretty much what you'd expect from their names :-).

One aspect of aggregate functions that people often find confusing is in queries like the below:

select facid, count ( * ) from cd . facilitiesTry it out, and you'll find that it doesn't work. This is because count(*) wants to collapse the facilities table into a single value - unfortunately, it can't do that, because there's a lot of different facids in cd.facilities - Postgres doesn't know which facid to pair the count with.

Instead, if you wanted a query that returns all the facids along with a count on each row, you can break the aggregation out into a subquery as below:

select facid,

( select count ( * ) from cd . facilities )

from cd . facilitiesWhen we have a subquery that returns a scalar value like this, Postgres knows to simply repeat the value for every row in cd.facilities.

Produce a count of the number of facilities that have a cost to guests of 10 or more.

| 数数 |

|---|

| 6 |

回答:

select count ( * ) from cd . facilities where guestcost >= 10 ; This one is only a simple modification to the previous question: we need to weed out the inexpensive facilities. This is easy to do using a WHERE clause. Our aggregation can now only see the expensive facilities.

Produce a count of the number of recommendations each member has made. Order by member ID.

预期结果:

| recommendedby | 数数 |

|---|---|

| 1 | 5 |

| 2 | 3 |

| 3 | 1 |

| 4 | 2 |

| 5 | 1 |

| 6 | 1 |

| 9 | 2 |

| 11 | 1 |

| 13 | 2 |

| 15 | 1 |

| 16 | 1 |

| 20 | 1 |

| 30 | 1 |

回答:

select recommendedby, count ( * )

from cd . members

where recommendedby is not null

group by recommendedby

order by recommendedby; Previously, we've seen that aggregation functions are applied to a column of values, and convert them into an aggregated scalar value. This is useful, but we often find that we don't want just a single aggregated result: for example, instead of knowing the total amount of money the club has made this month, I might want to know how much money each different facility has made, or which times of day were most lucrative.

In order to support this kind of behaviour, SQL has the GROUP BY construct. What this does is batch the data together into groups, and run the aggregation function separately for each group. When you specify a GROUP BY , the database produces an aggregated value for each distinct value in the supplied columns. In this case, we're saying 'for each distinct value of recommendedby, get me the number of times that value appears'.

Produce a list of the total number of slots booked per facility. For now, just produce an output table consisting of facility id and slots, sorted by facility id.

预期结果:

| facid | Total Slots |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1320 |

| 1 | 1278 |

| 2 | 1209 |

| 3 | 830 |

| 4 | 1404 |

| 5 | 228 |

| 6 | 1104 |

| 7 | 908 |

| 8 | 911 |

回答:

select facid, sum (slots) as " Total Slots "

from cd . bookings

group by facid

order by facid; Other than the fact that we've introduced the SUM aggregate function, there's not a great deal to say about this exercise. For each distinct facility id, the SUM function adds together everything in the slots column.

Produce a list of the total number of slots booked per facility in the month of September 2012. Produce an output table consisting of facility id and slots, sorted by the number of slots.

预期结果:

| facid | Total Slots |

|---|---|

| 5 | 122 |

| 3 | 422 |

| 7 | 426 |

| 8 | 471 |

| 6 | 540 |

| 2 | 570 |

| 1 | 588 |

| 0 | 591 |

| 4 | 648 |

回答:

select facid, sum (slots) as " Total Slots "

from cd . bookings

where

starttime >= ' 2012-09-01 '

and starttime < ' 2012-10-01 '

group by facid

order by sum (slots); This is only a minor alteration of our previous example. Remember that aggregation happens after the WHERE clause is evaluated: we thus use the WHERE to restrict the data we aggregate over, and our aggregation only sees data from a single month.

Produce a list of the total number of slots booked per facility per month in the year of 2012. Produce an output table consisting of facility id and slots, sorted by the id and month.

预期结果:

| facid | 月 | Total Slots |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 7 | 270 |

| 0 | 8 | 459 |

| 0 | 9 | 591 |

| 1 | 7 | 207 |

| 1 | 8 | 483 |

| 1 | 9 | 588 |

| 2 | 7 | 180 |

| 2 | 8 | 459 |

| 2 | 9 | 570 |

| 3 | 7 | 104 |

| 3 | 8 | 304 |

| 3 | 9 | 422 |

| 4 | 7 | 264 |

| 4 | 8 | 492 |

| 4 | 9 | 648 |

| 5 | 7 | 24 |

| 5 | 8 | 82 |

| 5 | 9 | 122 |

| 6 | 7 | 164 |

| 6 | 8 | 400 |

| 6 | 9 | 540 |

| 7 | 7 | 156 |

| 7 | 8 | 326 |

| 7 | 9 | 426 |

| 8 | 7 | 117 |

| 8 | 8 | 322 |

| 8 | 9 | 471 |

回答:

select facid, extract(month from starttime) as month, sum (slots) as " Total Slots "

from cd . bookings

where

starttime >= ' 2012-01-01 '

and starttime < ' 2013-01-01 '

group by facid, month

order by facid, month; The main piece of new functionality in this question is the EXTRACT function. EXTRACT allows you to get individual components of a timestamp, like day, month, year, etc. We group by the output of this function to provide per-month values. An alternative, if we needed to distinguish between the same month in different years, is to make use of the DATE_TRUNC function, which truncates a date to a given granularity.

It's also worth noting that this is the first time we've truly made use of the ability to group by more than one column.

Find the total number of members who have made at least one booking.

预期结果:

| 数数 |

|---|

| 30 |

回答:

select count (distinct memid) from cd . bookings Your first instinct may be to go for a subquery here. Something like the below:

select count ( * ) from

( select distinct memid from cd . bookings ) as mems This does work perfectly well, but we can simplify a touch with the help of a little extra knowledge in the form of COUNT DISTINCT . This does what you might expect, counting the distinct values in the passed column.

Produce a list of facilities with more than 1000 slots booked. Produce an output table consisting of facility id and hours, sorted by facility id.

预期结果:

| facid | Total Slots |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1320 |

| 1 | 1278 |

| 2 | 1209 |

| 4 | 1404 |

| 6 | 1104 |

回答:

select facid, sum (slots) as " Total Slots "

from cd . bookings

group by facid

having sum (slots) > 1000

order by facid It turns out that there's actually an SQL keyword designed to help with the filtering of output from aggregate functions. This keyword is HAVING .

The behaviour of HAVING is easily confused with that of WHERE . The best way to think about it is that in the context of a query with an aggregate function, WHERE is used to filter what data gets input into the aggregate function, while HAVING is used to filter the data once it is output from the function. Try experimenting to explore this difference!

Produce a list of facilities along with their total revenue. The output table should consist of facility name and revenue, sorted by revenue. Remember that there's a different cost for guests and members!

预期结果:

| 姓名 | 收入 |

|---|---|

| 乒乓球 | 180 |

| Snooker Table | 240 |

| Pool Table | 270 |

| Badminton Court | 1906.5 |

| Squash Court | 13468.0 |

| Tennis Court 1 | 13860 |

| Tennis Court 2 | 14310 |

| Massage Room 2 | 15810 |

| Massage Room 1 | 72540 |

回答:

select facs . name , sum (slots * case

when memid = 0 then facs . guestcost

else facs . membercost

end) as revenue

from cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

group by facs . name

order by revenue; The only real complexity in this query is that guests (member ID 0) have a different cost to everyone else. We use a case statement to produce the cost for each session, and then sum each of those sessions, grouped by facility.

Produce a list of facilities with a total revenue less than 1000. Produce an output table consisting of facility name and revenue, sorted by revenue. Remember that there's a different cost for guests and members!

预期结果:

| 姓名 | 收入 |

|---|---|

| 乒乓球 | 180 |

| Snooker Table | 240 |

| Pool Table | 270 |

回答:

select name, revenue from (

select facs . name , sum (case

when memid = 0 then slots * facs . guestcost

else slots * membercost

end) as revenue

from cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

group by facs . name

) as agg where revenue < 1000

order by revenue; You may well have tried to use the HAVING keyword we introduced in an earlier exercise, producing something like below:

select facs . name , sum (case

when memid = 0 then slots * facs . guestcost

else slots * membercost

end) as revenue

from cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

group by facs . name

having revenue < 1000

order by revenue; Unfortunately, this doesn't work! You'll get an error along the lines of ERROR: column "revenue" does not exist . Postgres, unlike some other RDBMSs like SQL Server and MySQL, doesn't support putting column names in the HAVING clause. This means that for this query to work, you'd have to produce something like below:

select facs . name , sum (case

when memid = 0 then slots * facs . guestcost

else slots * membercost

end) as revenue

from cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

group by facs . name

having sum (case

when memid = 0 then slots * facs . guestcost

else slots * membercost

end) < 1000

order by revenue; Having to repeat significant calculation code like this is messy, so our anointed solution instead just wraps the main query body as a subquery, and selects from it using a WHERE clause. In general, I recommend using HAVING for simple queries, as it increases clarity. Otherwise, this subquery approach is often easier to use.

Output the facility id that has the highest number of slots booked. For bonus points, try a version without a LIMIT clause. This version will probably look messy!

预期结果:

| facid | Total Slots |

|---|---|

| 4 | 1404 |

回答:

select facid, sum (slots) as " Total Slots "

from cd . bookings

group by facid

order by sum (slots) desc

LIMIT 1 ; Let's start off with what's arguably the simplest way to do this: produce a list of facility IDs and the total number of slots used, order by the total number of slots used, and pick only the top result.

It's worth realising, though, that this method has a significant weakness. In the event of a tie, we will still only get one result! To get all the relevant results, we might try using the MAX aggregate function, something like below:

select facid, max (totalslots) from (

select facid, sum (slots) as totalslots

from cd . bookings

group by facid

) as sub group by facid The intent of this query is to get the highest totalslots value and its associated facid(s). Unfortunately, this just won't work! In the event of multiple facids having the same number of slots booked, it would be ambiguous which facid should be paired up with the single (or scalar ) value coming out of the MAX function. This means that Postgres will tell you that facid ought to be in a GROUP BY section, which won't produce the results we're looking for.

Let's take a first stab at a working query:

select facid, sum (slots) as totalslots

from cd . bookings

group by facid

having sum (slots) = ( select max ( sum2 . totalslots ) from

( select sum (slots) as totalslots

from cd . bookings

group by facid

) as sum2);The query produces a list of facility IDs and number of slots used, and then uses a HAVING clause that works out the maximum totalslots value. We're essentially saying: 'produce a list of facids and their number of slots booked, and filter out all the ones that doen't have a number of slots booked equal to the maximum.'

Useful as HAVING is, however, our query is pretty ugly. To improve on that, let's introduce another new concept: Common Table Expressions (CTEs). CTEs can be thought of as allowing you to define a database view inline in your query. It's really helpful in situations like this, where you're having to repeat yourself a lot.

CTEs are declared in the form WITH CTEName as (SQL-Expression) . You can see our query redefined to use a CTE below:

with sum as ( select facid, sum (slots) as totalslots

from cd . bookings

group by facid

)

select facid, totalslots

from sum

where totalslots = ( select max (totalslots) from sum);You can see that we've factored out our repeated selections from cd.bookings into a single CTE, and made the query a lot simpler to read in the process!

BUT WAIT.还有更多。 It's also possible to complete this problem using Window Functions. We'll leave these until later, but even better solutions to problems like these are available.

That's a lot of information for a single exercise. Don't worry too much if you don't get it all right now - we'll reuse these concepts in later exercises.

Produce a list of the total number of slots booked per facility per month in the year of 2012. In this version, include output rows containing totals for all months per facility, and a total for all months for all facilities. The output table should consist of facility id, month and slots, sorted by the id and month. When calculating the aggregated values for all months and all facids, return null values in the month and facid columns.

预期结果:

| facid | 月 | 老虎机 |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 7 | 270 |

| 0 | 8 | 459 |

| 0 | 9 | 591 |

| 0 | 1320 | |

| 1 | 7 | 207 |

| 1 | 8 | 483 |

| 1 | 9 | 588 |

| 1 | 1278 | |

| 2 | 7 | 180 |

| 2 | 8 | 459 |

| 2 | 9 | 570 |

| 2 | 1209 | |

| 3 | 7 | 104 |

| 3 | 8 | 304 |

| 3 | 9 | 422 |

| 3 | 830 | |

| 4 | 7 | 264 |

| 4 | 8 | 492 |

| 4 | 9 | 648 |

| 4 | 1404 | |

| 5 | 7 | 24 |

| 5 | 8 | 82 |

| 5 | 9 | 122 |

| 5 | 228 | |

| 6 | 7 | 164 |

| 6 | 8 | 400 |

| 6 | 9 | 540 |

| 6 | 1104 | |

| 7 | 7 | 156 |

| 7 | 8 | 326 |

| 7 | 9 | 426 |

| 7 | 908 | |

| 8 | 7 | 117 |

| 8 | 8 | 322 |

| 8 | 9 | 471 |

| 8 | 910 | |

| 9191 |

回答:

select facid, extract(month from starttime) as month, sum (slots) as slots

from cd . bookings

where

starttime >= ' 2012-01-01 '

and starttime < ' 2013-01-01 '

group by rollup(facid, month)

order by facid, month; When we are doing data analysis, we sometimes want to perform multiple levels of aggregation to allow ourselves to 'zoom' in and out to different depths. In this case, we might be looking at each facility's overall usage, but then want to dive in to see how they've performed on a per-month basis. Using the SQL we know so far, it's quite cumbersome to produce a single query that does what we want - we effectively have to resort to concatenating multiple queries using UNION ALL :

select facid, extract(month from starttime) as month, sum (slots) as slots

from cd . bookings

where

starttime >= ' 2012-01-01 '

and starttime < ' 2013-01-01 '

group by facid, month

union all

select facid, null , sum (slots) as slots

from cd . bookings

where

starttime >= ' 2012-01-01 '

and starttime < ' 2013-01-01 '

group by facid

union all

select null , null , sum (slots) as slots

from cd . bookings

where

starttime >= ' 2012-01-01 '

and starttime < ' 2013-01-01 '

order by facid, month;As you can see, each subquery performs a different level of aggregation, and we just combine the results. We can clean this up a lot by factoring out commonalities using a CTE:

with bookings as (

select facid, extract(month from starttime) as month, slots

from cd . bookings

where

starttime >= ' 2012-01-01 '

and starttime < ' 2013-01-01 '

)

select facid, month, sum (slots) from bookings group by facid, month

union all

select facid, null , sum (slots) from bookings group by facid

union all

select null , null , sum (slots) from bookings

order by facid, month; This version is not excessively hard on the eyes, but it becomes cumbersome as the number of aggregation columns increases. Fortunately, PostgreSQL 9.5 introduced support for the ROLLUP operator, which we've used to simplify our accepted answer.

ROLLUP produces a hierarchy of aggregations in the order passed into it: for example, ROLLUP(facid, month) outputs aggregations on (facid, month), (facid), and (). If we wanted an aggregation of all facilities for a month (instead of all months for a facility) we'd have to reverse the order, using ROLLUP(month, facid) . Alternatively, if we instead want all possible permutations of the columns we pass in, we can use CUBE rather than ROLLUP . This will produce (facid, month), (month), (facid), and ().

ROLLUP and CUBE are special cases of GROUPING SETS . GROUPING SETS allow you to specify the exact aggregation permutations you want: you could, for example, ask for just (facid, month) and (facid), skipping the top-level aggregation.

Produce a list of the total number of hours booked per facility, remembering that a slot lasts half an hour. The output table should consist of the facility id, name, and hours booked, sorted by facility id. Try formatting the hours to two decimal places.

预期结果:

| facid | 姓名 | Total Hours |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 660.00 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 639.00 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 604.50 |

| 3 | 乒乓球 | 415.00 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 702.00 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 114.00 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 552.00 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 454.00 |

| 8 | Pool Table | 455.50 |

回答:

select facs . facid , facs . name ,

trim (to_char( sum ( bks . slots ) / 2 . 0 , ' 9999999999999999D99 ' )) as " Total Hours "

from cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . facilities facs

on facs . facid = bks . facid

group by facs . facid , facs . name

order by facs . facid ; There's a few little pieces of interest in this question. Firstly, you can see that our aggregation works just fine when we join to another table on a 1:1 basis. Also note that we group by both facs.facid and facs.name . This is might seem odd: after all, since facid is the primary key of the facilities table, each facid has exactly one name, and grouping by both fields is the same as grouping by facid alone. In fact, you'll find that if you remove facs.name from the GROUP BY clause, the query works just fine: Postgres works out that this 1:1 mapping exists, and doesn't insist that we group by both columns.

Unfortunately, depending on which database system we use, validation might not be so smart, and may not realise that the mapping is strictly 1:1. That being the case, if there were multiple names for each facid and we hadn't grouped by name , the DBMS would have to choose between multiple (equally valid) choices for the name . Since this is invalid, the database system will insist that we group by both fields. In general, I recommend grouping by all columns you don't have an aggregate function on: this will ensure better cross-platform compatibility.

Next up is the division. Those of you familiar with MySQL may be aware that integer divisions are automatically cast to floats. Postgres is a little more traditional in this respect, and expects you to tell it if you want a floating point division. You can do that easily in this case by dividing by 2.0 rather than 2.

Finally, let's take a look at formatting. The TO_CHAR function converts values to character strings. It takes a formatting string, which we specify as (up to) lots of numbers before the decimal place, decimal place, and two numbers after the decimal place. The output of this function can be prepended with a space, which is why we include the outer TRIM function.

Produce a list of each member name, id, and their first booking after September 1st 2012. Order by member ID.

预期结果:

| 姓 | 名 | memid | starttime |

|---|---|---|---|

| 客人 | 客人 | 0 | 2012-09-01 08:00:00 |

| 史密斯 | 达伦 | 1 | 2012-09-01 09:00:00 |

| 史密斯 | 特雷西 | 2 | 2012-09-01 11:30:00 |

| Rownam | 蒂姆 | 3 | 2012-09-01 16:00:00 |

| Joplette | 珍妮丝 | 4 | 2012-09-01 15:00:00 |

| Butters | 杰拉尔德 | 5 | 2012-09-02 12:30:00 |

| 特雷西 | 伯顿 | 6 | 2012-09-01 15:00:00 |

| 敢 | 南希 | 7 | 2012-09-01 12:30:00 |

| Boothe | 蒂姆 | 8 | 2012-09-01 08:30:00 |

| Stibbons | 思考 | 9 | 2012-09-01 11:00:00 |

| 欧文 | 查尔斯 | 10 | 2012-09-01 11:00:00 |

| 琼斯 | 大卫 | 11 | 2012-09-01 09:30:00 |

| 贝克 | 安妮 | 12 | 2012-09-01 14:30:00 |

| Farrell | Jemima | 13 | 2012-09-01 09:30:00 |

| 史密斯 | 杰克 | 14 | 2012-09-01 11:00:00 |

| 坏人 | 佛罗伦萨 | 15 | 2012-09-01 10:30:00 |

| 贝克 | 蒂莫西 | 16 | 2012-09-01 15:00:00 |

| Pinker | 大卫 | 17 | 2012-09-01 08:30:00 |

| Genting | 马修 | 20 | 2012-09-01 18:00:00 |

| 麦肯齐 | 安娜 | 21 | 2012-09-01 08:30:00 |

| Coplin | 琼 | 22 | 2012-09-02 11:30:00 |

| Sarwin | Ramnaresh | 24 | 2012-09-04 11:00:00 |

| 琼斯 | 道格拉斯 | 26 | 2012-09-08 13:00:00 |

| Rumney | 亨利埃塔 | 27 | 2012-09-16 13:30:00 |

| Farrell | 大卫 | 28 | 2012-09-18 09:00:00 |

| Worthington-Smyth | 亨利 | 29 | 2012-09-19 09:30:00 |

| 范围 | Millicent | 30 | 2012-09-19 11:30:00 |

| 特百惠 | 风信子 | 33 | 2012-09-20 08:00:00 |

| 打猎 | 约翰 | 35 | 2012-09-23 14:00:00 |

| Crumpet | 埃里卡 | 36 | 2012-09-27 11:30:00 |

回答:

select mems . surname , mems . firstname , mems . memid , min ( bks . starttime ) as starttime

from cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . members mems on

mems . memid = bks . memid

where starttime >= ' 2012-09-01 '

group by mems . surname , mems . firstname , mems . memid

order by mems . memid ; This answer demonstrates the use of aggregate functions on dates. MIN works exactly as you'd expect, pulling out the lowest possible date in the result set. To make this work, we need to ensure that the result set only contains dates from September onwards. We do this using the WHERE clause.

You might typically use a query like this to find a customer's next booking. You can use this by replacing the date '2012-09-01' with the function now()

Produce a list of member names, with each row containing the total member count. Order by join date.

预期结果:

| 数数 | 名 | 姓 |

|---|---|---|

| 31 | 客人 | 客人 |

| 31 | 达伦 | 史密斯 |

| 31 | 特雷西 | 史密斯 |

| 31 | 蒂姆 | Rownam |

| 31 | 珍妮丝 | Joplette |

| 31 | 杰拉尔德 | Butters |

| 31 | 伯顿 | 特雷西 |

| 31 | 南希 | 敢 |

| 31 | 蒂姆 | Boothe |

| 31 | 思考 | Stibbons |

| 31 | 查尔斯 | 欧文 |

| 31 | 大卫 | 琼斯 |

| 31 | 安妮 | 贝克 |

| 31 | Jemima | Farrell |

| 31 | 杰克 | 史密斯 |

| 31 | 佛罗伦萨 | 坏人 |

| 31 | 蒂莫西 | 贝克 |

| 31 | 大卫 | Pinker |

| 31 | 马修 | Genting |

| 31 | 安娜 | 麦肯齐 |

| 31 | 琼 | Coplin |

| 31 | Ramnaresh | Sarwin |

| 31 | 道格拉斯 | 琼斯 |

| 31 | 亨利埃塔 | Rumney |

| 31 | 大卫 | Farrell |

| 31 | 亨利 | Worthington-Smyth |

| 31 | Millicent | 范围 |

| 31 | 风信子 | 特百惠 |

| 31 | 约翰 | 打猎 |

| 31 | 埃里卡 | Crumpet |

| 31 | 达伦 | 史密斯 |

回答:

select count ( * ) over(), firstname, surname

from cd . members

order by joindate Using the knowledge we've built up so far, the most obvious answer to this is below. We use a subquery because otherwise SQL will require us to group by firstname and surname, producing a different result to what we're looking for.

select ( select count ( * ) from cd . members ) as count, firstname, surname

from cd . members

order by joindateThere's nothing at all wrong with this answer, but we've chosen a different approach to introduce a new concept called window functions. Window functions provide enormously powerful capabilities, in a form often more convenient than the standard aggregation functions. While this exercise is only a toy, we'll be working on more complicated examples in the near future.

Window functions operate on the result set of your (sub-)query, after the WHERE clause and all standard aggregation. They operate on a window of data. By default this is unrestricted: the entire result set, but it can be restricted to provide more useful results. For example, suppose instead of wanting the count of all members, we want the count of all members who joined in the same month as that member:

select count ( * ) over(partition by date_trunc( ' month ' ,joindate)),

firstname, surname

from cd . members

order by joindateIn this example, we partition the data by month. For each row the window function operates over, the window is any rows that have a joindate in the same month. The window function thus produces a count of the number of members who joined in that month.

You can go further. Imagine if, instead of the total number of members who joined that month, you want to know what number joinee they were that month. You can do this by adding in an ORDER BY to the window function:

select count ( * ) over(partition by date_trunc( ' month ' ,joindate) order by joindate),

firstname, surname

from cd . members

order by joindate The ORDER BY changes the window again. Instead of the window for each row being the entire partition, the window goes from the start of the partition to the current row, and not beyond. Thus, for the first member who joins in a given month, the count is 1. For the second, the count is 2, and so on.

One final thing that's worth mentioning about window functions: you can have multiple unrelated ones in the same query. Try out the query below for an example - you'll see the numbers for the members going in opposite directions! This flexibility can lead to more concise, readable, and maintainable queries.

select count ( * ) over(partition by date_trunc( ' month ' ,joindate) order by joindate asc ),

count ( * ) over(partition by date_trunc( ' month ' ,joindate) order by joindate desc ),

firstname, surname

from cd . members

order by joindateWindow functions are extraordinarily powerful, and they will change the way you write and think about SQL. Make good use of them!

Produce a monotonically increasing numbered list of members, ordered by their date of joining. Remember that member IDs are not guaranteed to be sequential.

预期结果:

| row_number | 名 | 姓 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 客人 | 客人 |

| 2 | 达伦 | 史密斯 |

| 3 | 特雷西 | 史密斯 |

| 4 | 蒂姆 | Rownam |

| 5 | 珍妮丝 | Joplette |

| 6 | 杰拉尔德 | Butters |

| 7 | 伯顿 | 特雷西 |

| 8 | 南希 | 敢 |

| 9 | 蒂姆 | Boothe |

| 10 | 思考 | Stibbons |

| 11 | 查尔斯 | 欧文 |

| 12 | 大卫 | 琼斯 |

| 13 | 安妮 | 贝克 |

| 14 | Jemima | Farrell |

| 15 | 杰克 | 史密斯 |

| 16 | 佛罗伦萨 | 坏人 |

| 17 | 蒂莫西 | 贝克 |

| 18 | 大卫 | Pinker |

| 19 | 马修 | Genting |

| 20 | 安娜 | 麦肯齐 |

| 21 | 琼 | Coplin |

| 22 | Ramnaresh | Sarwin |

| 23 | 道格拉斯 | 琼斯 |

| 24 | 亨利埃塔 | Rumney |

| 25 | 大卫 | Farrell |

| 26 | 亨利 | Worthington-Smyth |

| 27 | Millicent | 范围 |

| 28 | 风信子 | 特百惠 |

| 29 | 约翰 | 打猎 |

| 30 | 埃里卡 | Crumpet |

| 31 | 达伦 | 史密斯 |

回答:

select row_number() over( order by joindate), firstname, surname

from cd . members

order by joindate This exercise is a simple bit of window function practise! You could just as easily use count(*) over(order by joindate) here, so don't worry if you used that instead.

In this query, we don't define a partition, meaning that the partition is the entire dataset. Since we define an order for the window function, for any given row the window is: start of the dataset -> current row.

Output the facility id that has the highest number of slots booked. Ensure that in the event of a tie, all tieing results get output.

预期结果:

| facid | 全部的 |

|---|---|

| 4 | 1404 |

回答:

select facid, total from (

select facid, sum (slots) total, rank() over ( order by sum (slots) desc ) rank

from cd . bookings

group by facid

) as ranked

where rank = 1 You may recall that this is a problem we've already solved in an earlier exercise. We came up with an answer something like below, which we then cut down using CTEs:

select facid, sum (slots) as totalslots

from cd . bookings

group by facid

having sum (slots) = ( select max ( sum2 . totalslots ) from

( select sum (slots) as totalslots

from cd . bookings

group by facid

) as sum2);Once we've cleaned it up, this solution is perfectly adequate. Explaining how the query works makes it seem a little odd, though - 'find the number of slots booked by the best facility. Calculate the total slots booked for each facility, and return only the rows where the slots booked are the same as for the best'. Wouldn't it be nicer to be able to say 'calculate the number of slots booked for each facility, rank them, and pick out any at rank 1'?

Fortunately, window functions allow us to do this - although it's fair to say that doing so is not trivial to the untrained eye. The first key piece of information is the existence of the éfunction. This ranks values based on the ORDER BY that is passed to it. If there's a tie for (say) second place), the next gets ranked at position 4. So, what we need to do is get the number of slots for each facility, rank them, and pick off the ones at the top rank. A first pass at this might look something like the below:

select facid, total from (

select facid, total, rank() over ( order by total desc ) rank from (

select facid, sum (slots) total

from cd . bookings

group by facid

) as sumslots

) as ranked

where rank = 1 The inner query calculates the total slots booked, the middle one ranks them, and the outer one creams off the top ranked. We can actually tidy this up a little: recall that window function get applied pretty late in the select function, after aggregation. That being the case, we can move the aggregation into the ORDER BY part of the function, as shown in the approved answer.

While the window function approach isn't massively simpler in terms of lines of code, it arguably makes more semantic sense.

Produce a list of members, along with the number of hours they've booked in facilities, rounded to the nearest ten hours. Rank them by this rounded figure, producing output of first name, surname, rounded hours, rank. Sort by rank, surname, and first name.

预期结果:

| 名 | 姓 | 小时 | 秩 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 客人 | 客人 | 1200 | 1 |

| 达伦 | 史密斯 | 340 | 2 |

| 蒂姆 | Rownam | 330 | 3 |

| 蒂姆 | Boothe | 220 | 4 |

| 特雷西 | 史密斯 | 220 | 4 |

| 杰拉尔德 | Butters | 210 | 6 |

| 伯顿 | 特雷西 | 180 | 7 |

| 查尔斯 | 欧文 | 170 | 8 |

| 珍妮丝 | Joplette | 160 | 9 |

| 安妮 | 贝克 | 150 | 10 |

| 蒂莫西 | 贝克 | 150 | 10 |

| 大卫 | 琼斯 | 150 | 10 |