Dies ist eine Zusammenstellung aller Fragen und Antworten zu Alisdair Owens Postgresql -Übungen. Denken Sie daran, dass Sie dazu führen, dass Sie dazu führen, dass Sie weiter als nur diesen Leitfaden durchfliegen. Wenn Sie also Postgresql -Übungen für einen Besuch zahlen.

Es ist ziemlich einfach, mit den Übungen in Gang zu gehen: Alles, was Sie tun müssen, ist die Übungen zu öffnen, sich die Fragen anzusehen und sie zu beantworten!

Der Datensatz für diese Übungen gilt für einen neu erstellten Country Club mit einer Reihe von Mitgliedern, Einrichtungen wie Tennisplätzen und der Buchungsgeschichte für diese Einrichtungen. Unter anderem möchte der Club verstehen, wie er seine Informationen nutzen kann, um die Einrichtungsnutzung/-nachfrage zu analysieren. Bitte beachten Sie: Dieser Datensatz ist nur für die Unterstützung einer interessanten Auswahl von Übungen konzipiert, und das Datenbankschema ist in mehreren Aspekten fehlerhaft. Bitte nehmen Sie es nicht als Beispiel für ein gutes Design. Wir werden mit einem Blick auf den Mitgliedertisch beginnen:

CREATE TABLE cd .members

(

memid integer NOT NULL ,

surname character varying ( 200 ) NOT NULL ,

firstname character varying ( 200 ) NOT NULL ,

address character varying ( 300 ) NOT NULL ,

zipcode integer NOT NULL ,

telephone character varying ( 20 ) NOT NULL ,

recommendedby integer ,

joindate timestamp not null ,

CONSTRAINT members_pk PRIMARY KEY (memid),

CONSTRAINT fk_members_recommendedby FOREIGN KEY (recommendedby)

REFERENCES cd . members (memid) ON DELETE SET NULL

);Jedes Mitglied verfügt über eine ID (nicht garantiert sequentiell), grundlegende Adressinformationen, einen Verweis auf das Mitglied, das sie empfohlen hat (falls vorhanden), und einen Zeitstempel, wenn es sich angeschlossen hat. Die Adressen im Datensatz sind vollständig (und unrealistisch) hergestellt.

CREATE TABLE cd .facilities

(

facid integer NOT NULL ,

name character varying ( 100 ) NOT NULL ,

membercost numeric NOT NULL ,

guestcost numeric NOT NULL ,

initialoutlay numeric NOT NULL ,

monthlymaintenance numeric NOT NULL ,

CONSTRAINT facilities_pk PRIMARY KEY (facid)

);In der Tabelle der Einrichtungen werden alle buchbaren Einrichtungen aufgeführt, die der Country Club besitzt. Der Club speichert ID/Namensinformationen, die Kosten, um sowohl Mitglieder als auch Gäste zu buchen, die anfänglichen Kosten für den Bau der Einrichtung und schätzten die monatlichen Unterhaltskosten. Sie hoffen, diese Informationen zu nutzen, um zu verfolgen, wie sich jede Einrichtung finanziell lohnt.

CREATE TABLE cd .bookings

(

bookid integer NOT NULL ,

facid integer NOT NULL ,

memid integer NOT NULL ,

starttime timestamp NOT NULL ,

slots integer NOT NULL ,

CONSTRAINT bookings_pk PRIMARY KEY (bookid),

CONSTRAINT fk_bookings_facid FOREIGN KEY (facid) REFERENCES cd . facilities (facid),

CONSTRAINT fk_bookings_memid FOREIGN KEY (memid) REFERENCES cd . members (memid)

);Schließlich gibt es einen Tischverfolgungsbuch von Einrichtungen. Dies speichert den Facility -ID, das Mitglied, das die Buchung vorgenommen hat, zum Beginn der Buchung und wie viele halbstündige 'Slots' die Buchung gemacht wurde. Dieses eigenwillige Design wird bestimmte Abfragen schwieriger machen, sollte Ihnen jedoch einige interessante Herausforderungen stellen-sowie Sie auf den Schrecken vorbereiten, mit einigen realen Datenbanken zu arbeiten :-).

Okay, das sollte alle Informationen sein, die Sie benötigen. Sie können eine Abfragekategorie auswählen, die Sie aus dem obigen Menü ausprobieren können, oder von Anfang an alternativ beginnen.

Kein Problem! Das Laufen ist nicht zu schwer. Erstens benötigen Sie eine Installation von PostgreSQL, die Sie von hier aus erhalten können. Sobald Sie es gestartet haben, laden Sie die SQL herunter.

Führen Sie schließlich psql -U <username> -f clubdata.sql -d postgres -x -q aus, um die Datenbank der 'Übungen' zu erstellen. das C -Gebietsschema)

Wenn Sie Fragen ausführen, finden Sie PSQL möglicherweise ein wenig klobig. In diesem Fall empfehle ich, PGADMIN oder die Eclipse -Datenbankentwicklungs -Tools auszuprobieren.

Diese Kategorie befasst sich mit den Grundlagen von SQL. Es umfasst die Auswahl und wo Klauseln, Fallausdrücke, Gewerkschaften und einige andere Chancen und enden. Wenn Sie bereits in SQL ausgebildet sind, werden Sie diese Übungen wahrscheinlich ziemlich einfach finden. Wenn nicht, sollten Sie sie für einen guten Punkt finden, um für die schwierigeren Kategorien vor uns zu lernen!

Wenn Sie mit diesen Fragen zu kämpfen haben, empfehle ich dringend, SQL von Alan Beaulieu als prägnantes und gut geschriebenes Buch zu diesem Thema zu lernen. Wenn Sie an den Grundlagen von Datenbanksystemen interessiert sind (im Gegensatz zu genau der Verwendung), sollten Sie auch eine Einführung in Datenbanksysteme nach CJ -Datum untersuchen.

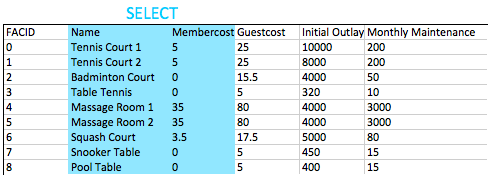

Wie können Sie alle Informationen aus der Tabelle CD.Facities abrufen?

Erwartete Ergebnisse:

| Gesicht | Name | Mitgliedskost | GuestCost | initialoutlay | Monatliche Wartung |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennisplatz 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennisplatz 2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | Tischtennis | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massageraum 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massageraum 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Kürbisgericht | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker -Tisch | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Billardtisch | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

Antwort:

select * from cd . facilities ; Die SELECT ist der grundlegende Startblock für Abfragen, die Informationen aus der Datenbank herauslesen. Eine minimale Auswahlanweisung besteht im Allgemeinen aus select [some set of columns] from [some table or group of tables] .

In diesem Fall möchten wir alle Informationen aus der Tabelle der Einrichtungen. Der Abschnitt ist einfach - wir müssen nur die cd.facilities -Tabelle angeben. 'CD' ist das Schema der Tabelle - ein Begriff, der für eine logische Gruppierung verwandter Informationen in der Datenbank verwendet wird.

Als nächstes müssen wir angeben, dass wir alle Spalten wollen. Praktischerweise gibt es eine Abkürzung für "alle Säulen" - *. Wir können dies verwenden, anstatt alle Spaltennamen mühsam anzugeben.

Sie möchten eine Liste aller Einrichtungen und ihrer Kosten für Mitglieder ausdrucken. Wie würden Sie eine Liste nur von den Namen und Kosten für Einrichtungen abrufen?

Erwartete Ergebnisse:

| Name | Mitgliedskost |

|---|---|

| Tennisplatz 1 | 5 |

| Tennisplatz 2 | 5 |

| Badminton Court | 0 |

| Tischtennis | 0 |

| Massageraum 1 | 35 |

| Massageraum 2 | 35 |

| Kürbisgericht | 3.5 |

| Snooker -Tisch | 0 |

| Billardtisch | 0 |

Antwort:

select name, membercost from cd . facilities ; Für diese Frage müssen wir die gewünschten Spalten angeben. Wir können dies mit einer einfachen, von Kommas mit Delimited-Liste der in der Auswahlanweisung angegebenen Spaltennamen tun. Alles in der Datenbank wird die in der Ab -Klausel verfügbaren Spalten betrachtet und die von uns gefragten zurückgeben, wie unten dargestellt

Im Allgemeinen gilt für Nicht-Throwaway-Abfragen als wünschenswert, die Namen der gewünschten Spalten in Ihren Abfragen zu geben, anstatt *zu verwenden. Dies liegt daran, dass Ihre Bewerbung möglicherweise nicht in der Lage ist, damit fertig zu werden, wenn mehr Spalten in die Tabelle hinzugefügt werden.

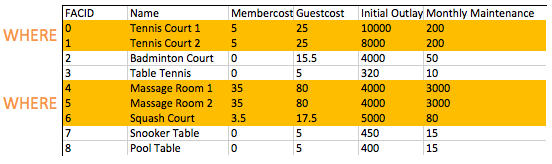

Wie können Sie eine Liste von Einrichtungen erstellen, die den Mitgliedern eine Gebühr erheben?

Erwartete Ergebnisse:

| Gesicht | Name | Mitgliedskost | GuestCost | initialoutlay | Monatliche Wartung |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennisplatz 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennisplatz 2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 4 | Massageraum 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massageraum 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Kürbisgericht | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

Antwort:

select * from cd . facilities where membercost > 0 ; Die FROM -Klausel wird verwendet, um eine Reihe von Kandidatenreihen aufzubauen, um Ergebnisse zu lesen. In unseren bisherigen Beispielen war diese Reihe von Zeilen einfach der Inhalt einer Tabelle. In Zukunft werden wir das Zusammenschluss untersuchen, was es uns ermöglicht, viel interessantere Kandidaten zu schaffen.

Sobald wir unsere Kandidatenreihen aufgebaut haben, ermöglicht die WHERE , für die Zeilen, an denen wir interessiert sind, zu filtern - in diesem Fall diejenigen mit einem Mitglied von mehr als Null. Wie Sie in späteren Übungen sehen werden, WHERE Klauseln mehrere Komponenten in Kombination mit einer WHERE Logik haben können, ist es möglich, nach Einrichtungen mit einer Kosten von mehr als 0 und weniger als 10 zu suchen.

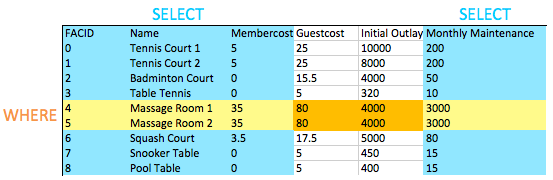

Wie können Sie eine Liste von Einrichtungen erstellen, die den Mitgliedern eine Gebühr erheben, und diese Gebühr beträgt weniger als 1/50 der monatlichen Wartungskosten? Geben Sie den Namen, den Namen der Einrichtungen, die Mitgliederkosten und die monatliche Wartung der fraglichen Einrichtungen zurück.

Erwartete Ergebnisse:

| Gesicht | Name | Mitgliedskost | Monatliche Wartung |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Massageraum 1 | 35 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massageraum 2 | 35 | 3000 |

Antwort:

select facid, name, membercost, monthlymaintenance

from cd . facilities

where

membercost > 0 and

(membercost < monthlymaintenance / 50 . 0 ); In der WHERE -Klausel können wir die Zeilen filtern, an denen wir interessiert sind - in diesem Fall diejenigen mit einem Mitgliedskost von mehr als Null und weniger als 1/50 der monatlichen Wartungskosten. Wie Sie sehen können, sind die Massageberäte dank der Personalkosten sehr teuer zu laufen!

Wenn wir zwei oder mehr Bedingungen testen wollen, verwenden wir sie AND kombinieren sie. Wir können, wie Sie vielleicht erwarten, verwenden OR testen können, ob ein Paar von Bedingungen wahr ist.

Möglicherweise haben Sie festgestellt, dass dies unsere erste Abfrage ist, die eine WHERE -Klausel mit Auswahl bestimmter Spalten kombiniert. Sie können im Bild unten sehen: Die Schnittstelle der ausgewählten Spalten und der ausgewählten Zeilen gibt uns die Daten zur Rückgabe. Dies scheint jetzt nicht zu interessant zu sein, aber wenn wir komplexere Operationen wie Joins später hinzufügen, werden Sie die einfache Eleganz dieses Verhaltens sehen.

Wie können Sie eine Liste aller Einrichtungen mit dem Wort "Tennis" in ihrem Namen erstellen?

Erwartete Ergebnisse:

| Gesicht | Name | Mitgliedskost | GuestCost | initialoutlay | Monatliche Wartung |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennisplatz 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennisplatz 2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 3 | Tischtennis | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

Antwort:

select *

from cd . facilities

where

name like ' %Tennis% ' ; SQLs LIKE Operator bietet einfache Muster -Anpassungen für Saiten. Es ist ziemlich allgemein implementiert und ist schön und einfach zu bedienen - es nimmt nur eine Zeichenfolge mit dem % -Scharn an, das zu einer Zeichenfolge passt, und _ für ein einzelnes Zeichen. In diesem Fall suchen wir nach Namen, die das Wort "Tennis" enthalten, sodass ein % auf beide Seiten in die Rechnung passt.

Es gibt andere Möglichkeiten, diese Aufgabe zu erfüllen: Postgres unterstützt beispielsweise regelmäßige Ausdrücke mit dem ~ Operator. Verwenden Sie alles, was Sie sich wohl fühlen, aber sind Sie sich bewusst, dass der LIKE Betreiber zwischen den Systemen viel tragbarer ist.

Wie können Sie die Details von Einrichtungen mit ID 1 und 5 abrufen? Versuchen Sie es, es ohne den oder den Bediener zu tun.

Erwartete Ergebnisse:

| Gesicht | Name | Mitgliedskost | GuestCost | initialoutlay | Monatliche Wartung |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tennisplatz 2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 5 | Massageraum 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

Antwort:

select *

from cd . facilities

where

facid in ( 1 , 5 ); Die offensichtliche Antwort auf diese Frage ist, eine WHERE -Klausel zu verwenden, die so aussieht, als where facid = 1 or facid = 5 . Eine Alternative, die bei einer großen Anzahl möglicher Übereinstimmungen einfacher ist, ist der IN . Der IN -Operator nimmt eine Liste möglicher Werte an und entspricht ihnen gegen (in diesem Fall) der Gesichtspunkte. Wenn einer der Werte übereinstimmt, gilt die WHERE -Klausel für diese Zeile, und die Zeile wird zurückgegeben.

Der IN -Operator ist ein guter früher Demonstrator der Eleganz des relationalen Modells. Das Argument, das es nimmt, ist nicht nur eine Liste von Werten - es ist tatsächlich eine Tabelle mit einer einzelnen Spalte. Da Abfragen auch Tabellen zurückgeben, können Sie diese Ergebnisse in einen IN -Operator einfügen, wenn Sie eine Abfrage erstellen, die eine einzelne Spalte zurückgibt. Ein Spielzeugbeispiel geben:

select *

from cd . facilities

where

facid in (

select facid from cd . facilities

);Dieses Beispiel entspricht funktional der Auswahl aller Einrichtungen, zeigt jedoch, wie Sie die Ergebnisse einer Abfrage in eine andere einfügen. Die innere Abfrage wird als Unterabfrage bezeichnet.

Wie können Sie eine Liste von Einrichtungen erstellen, wobei jedes als "billig" oder "teuer" bezeichnet wird, je nachdem, ob ihre monatlichen Wartungskosten mehr als 100 US -Dollar beträgt? Geben Sie den Namen und die monatliche Wartung der fraglichen Einrichtungen zurück.

Erwartete Ergebnisse:

| Name | kosten |

|---|---|

| Tennisplatz 1 | teuer |

| Tennisplatz 2 | teuer |

| Badminton Court | billig |

| Tischtennis | billig |

| Massageraum 1 | teuer |

| Massageraum 2 | teuer |

| Kürbisgericht | billig |

| Snooker -Tisch | billig |

| Billardtisch | billig |

Antwort:

select name,

case when (monthlymaintenance > 100 ) then

' expensive '

else

' cheap '

end as cost

from cd . facilities ; Diese Übung enthält einige neue Konzepte. Die erste ist die Tatsache, dass wir im Bereich der Abfrage zwischen SELECT und FROM berechnet werden. Früher haben wir dies nur verwendet, um Spalten auszuwählen, die wir zurückkehren möchten, aber Sie können hier alles einfügen, das ein einziges Ergebnis pro zurückgegebener Zeile erzeugt - einschließlich Unterabfragen.

Das zweite neue Konzept ist die CASE selbst. CASE ist effektiv, wenn/Switch -Anweisungen in anderen Sprachen mit einem Formular wie in der Abfrage gezeigt. Um eine "mittelmäßige" Option hinzuzufügen, würden wir einfach einen weiteren einfügen when...then der Abschnitt.

Schließlich gibt es den AS Operator. Dies wird einfach verwendet, um Spalten oder Ausdrücke zu kennzeichnen, damit sie besser angezeigt werden oder sie leichter zu verweisen, wenn sie als Teil einer Unterabfrage verwendet werden.

Wie können Sie eine Liste von Mitgliedern erstellen, die nach Anfang September 2012 beigetreten sind? Geben Sie den Memid, den Nachnamen, den FirstName und gemeinsam der fraglichen Mitglieder zurück.

Erwartete Ergebnisse:

| Memid | Nachname | Erstname | zusammen |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | Sarwin | Ramnaresh | 2012-09-01 08:44:42 |

| 26 | Jones | Douglas | 2012-09-02 18:43:05 |

| 27 | Rumney | Henrietta | 2012-09-05 08:42:35 |

| 28 | Farrell | David | 2012-09-15 08:22:05 |

| 29 | Worthington-Smyth | Henry | 2012-09-17 12:27:15 |

| 30 | Aufgabe | Millicent | 2012-09-18 19:04:01 |

| 33 | Tupperware | Hyazinthe | 2012-09-18 19:32:05 |

| 35 | Jagd | John | 2012-09-19 11:32:45 |

| 36 | Crumpet | Erica | 2012-09-22 08:36:38 |

| 37 | Schmied | Darren | 2012-09-26 18:08:45 |

Antwort:

select memid, surname, firstname, joindate

from cd . members

where joindate >= ' 2012-09-01 ' ; Dies ist unser erster Blick auf SQL Timestemps. Sie sind in absteigender Größenordnung formatiert: YYYY-MM-DD HH:MM:SS.nnnnnn . Wir können sie genauso vergleichen wie ein Unix -Zeitstempel, obwohl es etwas mehr involviert (und mächtig!) Es ist etwas mehr involviert (und mächtig!). In diesem Fall haben wir gerade den Datumsanteil des Zeitstempels angegeben. Dies wird automatisch von Postgres in den vollständigen Timestamp 2012-09-01 00:00:00 gegossen.

Wie können Sie eine bestellte Liste der ersten 10 Nachnamen in der Mitgliedertabelle erstellen? Die Liste darf keine Duplikate enthalten.

Erwartete Ergebnisse:

| Nachname |

|---|

| Bader |

| Bäcker |

| Stand |

| Butters |

| Coplin |

| Crumpet |

| Wagen |

| Farrell |

| GAST |

| Genting |

Antwort:

select distinct surname

from cd . members

order by surname

limit 10 ; Hier gibt es drei neue Konzepte, aber sie sind alle ziemlich einfach.

DISTINCT nach SELECT wird doppelte Zeilen aus dem Ergebnissatz entfernt. Beachten Sie, dass dies für Zeilen gilt: Wenn Zeile A mehrere Spalten enthält, ist Zeile B nur gleich, wenn die Werte in allen Spalten gleich sind. Verwenden Sie in der Regel nicht DISTINCT , dass Sie sich nicht milles Weise befinden-es ist nicht frei, Duplikate aus großen Abfrageergebnis-Sets zu entfernen.ORDER BY ( FROM und WHERE Klauseln gegen Ende der Abfrage) ermöglicht, die Ergebnisse durch eine Spalte oder eine Reihe von Spalten (Comma getrennt) zu bestellen.LIMIT können Sie die Anzahl der abgerufenen Ergebnisse begrenzen. Dies ist nützlich, um Ergebnisse jeweils eine Seite zu erhalten, und kann mit dem OFFSET -Keyword kombiniert werden, um folgende Seiten zu erhalten. Dies ist der gleiche Ansatz, der von MySQL verwendet wird und sehr bequem ist - Sie können leider feststellen, dass dieser Prozess in anderen DBs etwas komplizierter ist.Sie möchten aus irgendeinem Grund eine kombinierte Liste aller Nachnamen und aller Einrichtungsnamen. Ja, dies ist ein erfundenes Beispiel :-). Erstellen Sie diese Liste!

Erwartete Ergebnisse:

| Nachname |

|---|

| Tennisplatz 2 |

| Worthington-Smyth |

| Badminton Court |

| Pinker |

| Wagen |

| Bader |

| Mackenzie |

| Crumpet |

| Massageraum 1 |

| Kürbisgericht |

Antwort:

select surname

from cd . members

union

select name

from cd . facilities ; Der UNION macht das, was Sie erwarten könnten: kombiniert die Ergebnisse von zwei SQL -Abfragen in eine einzelne Tabelle. Die Einschränkung besteht darin, dass beide Ergebnisse der beiden Abfragen die gleiche Anzahl von Spalten und kompatiblen Datentypen haben müssen.

UNION entfernt doppelte Reihen, während UNION ALL nicht. Verwenden Sie UNION ALL standardmäßig, es sei denn, Sie kümmern sich um doppelte Ergebnisse.

Sie möchten das Anmeldedatum Ihres letzten Mitglieds erhalten. Wie können Sie diese Informationen abrufen?

Erwartete Ergebnisse:

| letzte |

|---|

| 2012-09-26 18:08:45 |

Antwort:

select max (joindate) as latest

from cd . members ; Dies ist unser erster Ausflug in die Gesamtfunktionen von SQL. Sie werden verwendet, um Informationen über ganze Gruppen von Zeilen zu extrahieren und es uns zu ermöglichen, leicht Fragen zu stellen wie:

Die MAX -Aggregat -Funktion hier ist sehr einfach: Sie empfängt alle möglichen Werte für Joindate und gibt den größten aus. Es gibt viel mehr Kraft, um Funktionen zu aggregieren, auf die Sie in zukünftigen Übungen stoßen werden.

Sie möchten den ersten und Nachnamen der letzten Mitglieder bekommen, die sich angemeldet haben - nicht nur das Datum. Wie kannst du das machen?

Erwartete Ergebnisse:

| Erstname | Nachname | zusammen |

|---|---|---|

| Darren | Schmied | 2012-09-26 18:08:45 |

Antwort:

select firstname, surname, joindate

from cd . members

where joindate =

( select max (joindate)

from cd . members ); In dem vorgeschlagenen Ansatz oben verwenden Sie eine Unterabfrage , um herauszufinden, was die jüngste Joindate ist. Diese Unterabfrage gibt eine skalare Tabelle zurück - dh eine Tabelle mit einer einzelnen Spalte und einer einzelnen Zeile. Da wir nur einen einzelnen Wert haben, können wir die Unterabfrage überall ersetzen, wo wir möglicherweise einen einzigen konstanten Wert setzen. In diesem Fall verwenden wir es, um die WHERE einer Abfrage zu vervollständigen, um ein bestimmtes Mitglied zu finden.

Sie könnten hoffen, dass Sie so etwas wie unten tun können:

select firstname, surname, max (joindate)

from cd . members Leider funktioniert das nicht. Die MAX -Funktion schränkt die Zeilen nicht so ein, wie die WHERE -Klausel - sie nimmt einfach eine Reihe von Werten ein und gibt den größten zurück. Die Datenbank bleibt dann gefragt, wie man eine lange Liste von Namen mit dem einzigen Join -Datum, der aus der MAX -Funktion stammt, kombiniert und fehlschlägt. Stattdessen müssen Sie sagen: "Finden Sie mir die Reihe (en), die ein Verbindungdatum haben, das dem maximalen Join -Datum entspricht."

Wie der Hinweis erwähnt, gibt es andere Möglichkeiten, diesen Job zu erledigen - ein Beispiel ist unten. Bei diesem Ansatz bestellen wir einfach ausdrücklich heraus, was das letzte Datum des letzten zusammengehaltenen Datums in der absteigenden Reihenfolge des Verbindungsdatums bestellen und den ersten abnehmen. Beachten Sie, dass dieser Ansatz nicht die äußerst unwahrscheinliche Eventualität von zwei Personen abdeckt, die genau zur gleichen Zeit beigetreten sind :-).

select firstname, surname, joindate

from cd . members

order by joindate desc

limit 1 ;Diese Kategorie befasst sich hauptsächlich mit einem grundlegenden Konzept in relationalen Datenbanksystemen: Joining. Mit Join können Sie verwandte Informationen aus mehreren Tabellen kombinieren, um eine Frage zu beantworten. Dies ist nicht nur vorteilhaft für die einfache Abfrage: Ein Mangel an Join -Fähigkeit fördert die Denormalisierung von Daten, wodurch die Komplexität der Innenkonsistent angehalten wird.

Dieses Thema deckt innere, äußere und Selbstverbindungen ab und verbringt ein wenig Zeit mit Unterabfragen (Abfragen innerhalb von Abfragen). Wenn Sie mit diesen Fragen zu kämpfen haben, empfehle ich dringend, SQL von Alan Beaulieu als prägnantes und gut geschriebenes Buch zu diesem Thema zu lernen.

Wie können Sie eine Liste der Anfangszeiten für Buchungen von Mitgliedern namens "David Farrell" erstellen?

Erwartete Ergebnisse:

| Startzeit |

|---|

| 2012-09-18 09:00:00 |

| 2012-09-18 17:30:00 |

| 2012-09-18 13:30:00 |

| 2012-09-18 20:00:00 |

| 2012-09-19 09:30:00 |

| 2012-09-19 15:00:00 |

| 2012-09-19 12:00:00 |

| 2012-09-20 15:30:00 |

| 2012-09-20 11:30:00 |

| 2012-09-20 14:00:00 |

Antwort:

select bks . starttime

from

cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . members mems

on mems . memid = bks . memid

where

mems . firstname = ' David '

and mems . surname = ' Farrell ' ; Die am häufigsten verwendete Art von Join ist der INNER JOIN . Dies kombiniert zwei Tabellen basierend auf einem Join -Ausdruck - in diesem Fall suchen wir für jede Mitglieds -ID in der Mitgliedertabelle nach passenden Werten in der Buchungstabelle. Wo wir eine Übereinstimmung finden, wird eine Zeile, die die Werte für jede Tabelle kombiniert, zurückgegeben. Beachten Sie, dass wir jeder Tabelle einen Alias (Bks und Mems) gegeben haben. Dies wird aus zwei Gründen verwendet: Erstens ist es bequem, und zweitens könnten wir uns mehrmals mit derselben Tabelle verbinden, sodass wir zwischen den Spalten von jeder verschiedenen Zeit, in der die Tabelle verbunden war, unterscheidet.

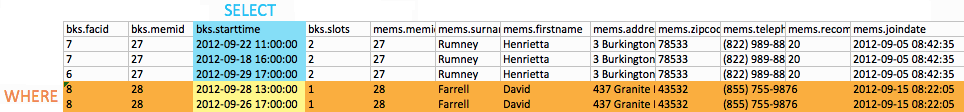

Ignorieren wir unsere Auswahl und wo vorerst Klauseln, und konzentrieren uns auf das, was die FROM hervorbringt. In all unseren früheren Beispielen war FROM gerade eine einfache Tabelle. Was ist es jetzt? Noch ein Tisch! Diesmal wird es als Komposit aus Buchungen und Mitgliedern produziert. Sie können eine Teilmenge der Ausgabe des Join unten sehen:

Für jedes Mitglied in der Mitgliedertabelle hat der Join alle passenden Mitglieder -IDs in der Buchungstabelle gefunden. Für jedes Match wird dann eine Zeile produziert, die die Zeile aus der Mitgliedertabelle und die Zeile aus der Buchungstabelle kombiniert.

Offensichtlich sind dies zu viele Informationen selbst, und jede nützliche Frage wird sie filtern. In unserer Abfrage verwenden wir den Beginn der SELECT -Klausel, um Spalten auszuwählen, und die WHERE -Klausel, um Zeilen auszuwählen, wie unten dargestellt:

Das ist alles, was wir brauchen, um Davids Buchungen zu finden! Im Allgemeinen ermutige ich Sie, sich daran zu erinnern, dass die Ausgabe der FROM -Klausel im Wesentlichen eine große Tabelle ist, aus der Sie dann Informationen herausfiltern. Das mag ineffizient klingen - aber keine Sorge, unter den Abdeckungen wird sich die DB viel intelligenter verhalten :-).

Ein letzter Anmerkung: Es gibt zwei verschiedene Syntaxen für innere Zusammenhänge. Ich habe dir das gezeigt, das ich bevorzuge, das ich mit anderen Join -Typen besser übereinstimme. Normalerweise sehen Sie eine andere Syntax, siehe unten:

select bks . starttime

from

cd . bookings bks,

cd . members mems

where

mems . firstname = ' David '

and mems . surname = ' Farrell '

and mems . memid = bks . memid ;Dies ist funktional genau das gleiche wie die genehmigte Antwort. Wenn Sie sich mit dieser Syntax wohler fühlen, können Sie sie gerne verwenden!

Wie können Sie eine Liste der Startzeiten für Buchungen für Tennisplätze für das Datum "2012-09-21" erstellen? Geben Sie eine Liste der Pairings für Startzeit und Einrichtungsname zurück, die bis zu diesem Zeitpunkt bestellt wurden.

Erwartete Ergebnisse:

| Start | Name |

|---|---|

| 2012-09-21 08:00:00 | Tennisplatz 1 |

| 2012-09-21 08:00:00 | Tennisplatz 2 |

| 2012-09-21 09:30:00 | Tennisplatz 1 |

| 2012-09-21 10:00:00 | Tennisplatz 2 |

| 2012-09-21 11:30:00 | Tennisplatz 2 |

| 2012-09-21 12:00:00 | Tennisplatz 1 |

| 2012-09-21 13:30:00 | Tennisplatz 1 |

| 2012-09-21 14:00:00 | Tennisplatz 2 |

| 2012-09-21 15:30:00 | Tennisplatz 1 |

| 2012-09-21 16:00:00 | Tennisplatz 2 |

| 2012-09-21 17:00:00 | Tennisplatz 1 |

| 2012-09-21 18:00:00 | Tennisplatz 2 |

Antwort:

select bks . starttime as start, facs . name as name

from

cd . facilities facs

inner join cd . bookings bks

on facs . facid = bks . facid

where

facs . facid in ( 0 , 1 ) and

bks . starttime >= ' 2012-09-21 ' and

bks . starttime < ' 2012-09-22 '

order by bks . starttime ; Dies ist eine weitere INNER JOIN Abfrage, obwohl es ein bisschen mehr Komplexität hat! Die FROM einem Teil der Abfrage ist einfach - wir schließen uns einfach zusammen mit Einrichtungen und Buchungen zusammen auf der Gesichtspunkte an. Dies erzeugt eine Tabelle, in der wir für jede Zeile in Buchungen detaillierte Informationen über die gebuchte Einrichtung beigefügt haben.

Auf die WHERE der Komponente der Abfrage. Die Überprüfungen der Starttime sind ziemlich selbsterklärend - wir stellen sicher, dass alle Buchungen zwischen den angegebenen Daten beginnen. Da wir nur an Tennisplätzen interessiert sind, verwenden wir auch den IN -Betreiber, um das Datenbanksystem zu sagen, dass wir uns nur die IDs 0 oder 1 zurückgeben sollen - die IDs der Gerichte. Es gibt andere Möglichkeiten, dies auszudrücken: Wir hätten verwenden können where facs.facid = 0 or facs.facid = 1 oder sogar where facs.name like 'Tennis%' verwendet werden.

Der Rest ist ziemlich einfach: Wir SELECT die Spalten aus, an denen wir interessiert sind, und ORDER BY zur Startzeit.

Wie können Sie eine Liste aller Mitglieder ausgeben, die ein anderes Mitglied empfohlen haben? Stellen Sie sicher, dass in der Liste keine Duplikate vorhanden sind und dass die Ergebnisse von (Nachname, FirstName) bestellt werden.

Erwartete Ergebnisse:

| Erstname | Nachname |

|---|---|

| Florenz | Bader |

| Timothy | Bäcker |

| Gerald | Butters |

| Jemima | Farrell |

| Matthew | Genting |

| David | Jones |

| Janice | JOPLETTE |

| Millicent | Aufgabe |

| Tim | Rownam |

| Darren | Schmied |

| Tracy | Schmied |

| Überlegen | Stibbons |

| Burton | Tracy |

Antwort:

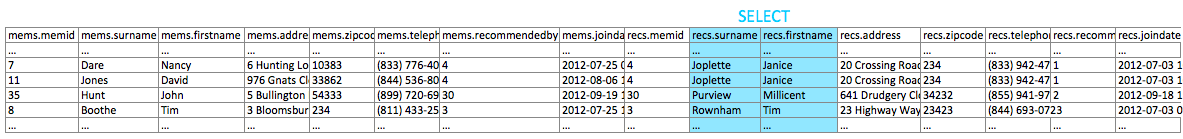

select distinct recs . firstname as firstname, recs . surname as surname

from

cd . members mems

inner join cd . members recs

on recs . memid = mems . recommendedby

order by surname, firstname; Hier ist ein Konzept, das manche Menschen verwirrend empfinden: Sie können sich einem Tisch an sich selbst anschließen! Dies ist sehr nützlich, wenn Sie Spalten haben, die Daten in derselben Tabelle verweisen, wie wir es mit empfohlenen von CD.MEMBERS empfohlen haben.

Wenn Sie Probleme haben, dies zu visualisieren, denken Sie daran, dass dies genauso wie jeder andere innere Join funktioniert. Unser Join nimmt jede Zeile in Mitgliedern mit einem empfohlenen Wert ein und schaut sich erneut in den Mitgliedern für die Zeile mit einer passenden Mitglieder -ID an. Anschließend erzeugt eine Ausgabezeile, die die beiden Mitgliedereinträge kombiniert. Dies sieht aus wie das folgende Diagramm:

Beachten Sie, dass wir zwar zwei "Nachname" -Spalten im Ausgangssatz haben, sie jedoch durch ihre Tischaliase unterschieden werden können. Sobald wir die gewünschten Spalten ausgewählt haben, verwenden wir einfach DISTINCT , um sicherzustellen, dass es keine Duplikate gibt.

Wie können Sie eine Liste aller Mitglieder ausgeben, einschließlich der Person, die sie empfohlen hat (falls vorhanden)? Stellen Sie sicher, dass die Ergebnisse von (Nachname, FirstName) bestellt werden.

Erwartete Ergebnisse:

| Memfname | Memsname | Recfnname | Recsname |

|---|---|---|---|

| Florenz | Bader | Überlegen | Stibbons |

| Anne | Bäcker | Überlegen | Stibbons |

| Timothy | Bäcker | Jemima | Farrell |

| Tim | Stand | Tim | Rownam |

| Gerald | Butters | Darren | Schmied |

| Joan | Coplin | Timothy | Bäcker |

| Erica | Crumpet | Tracy | Schmied |

| Nancy | Wagen | Janice | JOPLETTE |

| David | Farrell | ||

| Jemima | Farrell | ||

| GAST | GAST | ||

| Matthew | Genting | Gerald | Butters |

| John | Jagd | Millicent | Aufgabe |

| David | Jones | Janice | JOPLETTE |

| Douglas | Jones | David | Jones |

| Janice | JOPLETTE | Darren | Schmied |

| Anna | Mackenzie | Darren | Schmied |

| Charles | Owen | Darren | Schmied |

| David | Pinker | Jemima | Farrell |

| Millicent | Aufgabe | Tracy | Schmied |

| Tim | Rownam | ||

| Henrietta | Rumney | Matthew | Genting |

| Ramnaresh | Sarwin | Florenz | Bader |

| Darren | Schmied | ||

| Darren | Schmied | ||

| Jack | Schmied | Darren | Schmied |

| Tracy | Schmied | ||

| Überlegen | Stibbons | Burton | Tracy |

| Burton | Tracy | ||

| Hyazinthe | Tupperware | ||

| Henry | Worthington-Smyth | Tracy | Schmied |

Antwort:

select mems . firstname as memfname, mems . surname as memsname, recs . firstname as recfname, recs . surname as recsname

from

cd . members mems

left outer join cd . members recs

on recs . memid = mems . recommendedby

order by memsname, memfname; Lasst uns ein weiteres neues Konzept vorstellen: den LEFT OUTER JOIN . Diese werden am besten durch die Art und Weise erklärt, wie sie sich von den inneren Anschlüssen unterscheiden. Innenverbindungen nehmen einen linken und einen rechten Tisch und suchen nach passenden Zeilen, die auf einer Join -Bedingung ( ON ) basieren. Wenn die Bedingung erfüllt ist, wird eine zusammengeführte Reihe erzeugt. Ein LEFT OUTER JOIN funktioniert ähnlich, außer dass eine bestimmte Zeile in der linken Handtabelle nichts übereinstimmt, sondern immer noch eine Ausgangszeile erzeugt. Diese Ausgangszeile besteht aus der linken Tischreihe und einer Reihe von NULLS anstelle der rechten Tabellenzeile.

Dies ist in Situationen wie dieser Frage nützlich, in denen wir mit optionalen Daten Ausgaben erzeugen möchten. Wir wollen die Namen aller Mitglieder und den Namen ihres Empfehlends , wenn diese Person existiert . Sie können das mit einem inneren Join nicht richtig ausdrücken.

Wie Sie vielleicht vermutet haben, gibt es auch andere äußere Zusammenhänge. Der RIGHT OUTER JOIN ähnelt dem LEFT OUTER JOIN , außer dass die linke Seite des Ausdrucks diejenige ist, die die optionalen Daten enthält. Der selten verwendete FULL OUTER JOIN behandelt beide Seiten des Ausdrucks als optional.

Wie können Sie eine Liste aller Mitglieder erstellen, die ein Tennisplatz verwendet haben? Fügen Sie in Ihre Ausgabe den Namen des Gerichts und den Namen des als einzelnen Spalte formatierten Mitglieds ein. Stellen Sie keine doppelten Daten sicher und bestellen Sie nach dem Mitgliedsnamen.

Erwartete Ergebnisse:

| Mitglied | Einrichtung |

|---|---|

| Anne Baker | Tennisplatz 2 |

| Anne Baker | Tennisplatz 1 |

| Burton Tracy | Tennisplatz 2 |

| Burton Tracy | Tennisplatz 1 |

| Charles Owen | Tennisplatz 2 |

| Charles Owen | Tennisplatz 1 |

| Darren Smith | Tennisplatz 2 |

| David Farrell | Tennisplatz 2 |

| David Farrell | Tennisplatz 1 |

| David Jones | Tennisplatz 1 |

| David Jones | Tennisplatz 2 |

| David Pinker | Tennisplatz 1 |

| Douglas Jones | Tennisplatz 1 |

| Erica Crumpet | Tennisplatz 1 |

| Florence Bader | Tennisplatz 1 |

| Florence Bader | Tennisplatz 2 |

| Gast | Tennisplatz 2 |

| Gast | Tennisplatz 1 |

| Gerald Butters | Tennisplatz 1 |

| Gerald Butters | Tennisplatz 2 |

| Henrietta Rumney | Tennisplatz 2 |

| Jack Smith | Tennisplatz 1 |

| Jack Smith | Tennisplatz 2 |

| Janice Joplette | Tennisplatz 1 |

| Janice Joplette | Tennisplatz 2 |

| Jemima Farrell | Tennisplatz 2 |

| Jemima Farrell | Tennisplatz 1 |

| Joan Coplin | Tennisplatz 1 |

| John Hunt | Tennisplatz 1 |

| John Hunt | Tennisplatz 2 |

| Matthew Genting | Tennisplatz 1 |

| Millicent -Zuständigkeitsbereich | Tennisplatz 2 |

| Nancy Dare | Tennisplatz 2 |

| Nancy Dare | Tennisplatz 1 |

| Überlegen Sie Stibbons | Tennisplatz 2 |

| Überlegen Sie Stibbons | Tennisplatz 1 |

| Ramnaresh Sarwin | Tennisplatz 2 |

| Ramnaresh Sarwin | Tennisplatz 1 |

| Tim Boothe | Tennisplatz 1 |

| Tim Boothe | Tennisplatz 2 |

| Tim Rownam | Tennisplatz 1 |

| Tim Rownam | Tennisplatz 2 |

| Timothy Baker | Tennisplatz 2 |

| Timothy Baker | Tennisplatz 1 |

| Tracy Smith | Tennisplatz 2 |

| Tracy Smith | Tennisplatz 1 |

Antwort:

select distinct mems . firstname || ' ' || mems . surname as member, facs . name as facility

from

cd . members mems

inner join cd . bookings bks

on mems . memid = bks . memid

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

where

bks . facid in ( 0 , 1 )

order by member Diese Übung ist weitgehend eine komplexere Anwendung dessen, was Sie in früheren Fragen gelernt haben. Es ist auch das erste Mal, dass wir mehr als einen Join verwendet haben, was für einige ein wenig verwirrend sein kann. Denken Sie beim Lesen von Join -Ausdrücken daran, dass ein Join effektiv eine Funktion ist, die zwei Tabellen aufnimmt, eine mit der linken Tabelle und die andere die rechte. Dies ist leicht zu visualisieren mit nur einem Anschluss an der Abfrage, aber ein wenig verwirrender mit zwei.

Unsere zweite INNER JOIN in dieser Abfrage hat eine rechte Seite von CD.Facities. Das ist leicht genug zu verstehen. Die linke Seite ist jedoch die Tabelle, die durch den Beitritt zu CD.Members zu CD.Bookings zurückgegeben wird. Es ist wichtig, dies zu betonen: Das relationale Modell dreht sich alles um Tabellen. Die Ausgabe eines Join ist eine weitere Tabelle. Die Ausgabe einer Abfrage ist eine Tabelle. Single Columned Listen sind Tabellen. Sobald Sie das erfasst haben, haben Sie die grundlegende Schönheit des Modells erfasst.

Als letzte Notiz stellen wir hier eine neue Sache vor: das || Der Bediener wird verwendet, um Saiten zu verkettet.

Wie können Sie am Tag 2012-09-14 eine Liste von Buchungen erstellen, die das Mitglied (oder Gast) mehr als 30 US-Dollar kosten? Denken Sie daran, dass die Gäste unterschiedliche Kosten für Mitglieder haben (die aufgelisteten Kosten sind pro halbstündiger 'Slot'), und der Gastbenutzer ist immer id 0. In Ihren Ausgang den Namen der Einrichtung, den Namen des als einzelnen Spalte formierten Mitglieds und die Kosten einbeziehen. Bestellen Sie durch absteigende Kosten und verwenden Sie keine Unterabfragen.

Erwartete Ergebnisse:

| Mitglied | Einrichtung | kosten |

|---|---|---|

| Gast | Massageraum 2 | 320 |

| Gast | Massageraum 1 | 160 |

| Gast | Massageraum 1 | 160 |

| Gast | Massageraum 1 | 160 |

| Gast | Tennisplatz 2 | 150 |

| Jemima Farrell | Massageraum 1 | 140 |

| Gast | Tennisplatz 1 | 75 |

| Gast | Tennisplatz 2 | 75 |

| Gast | Tennisplatz 1 | 75 |

| Matthew Genting | Massageraum 1 | 70 |

| Florence Bader | Massageraum 2 | 70 |

| Gast | Kürbisgericht | 70.0 |

| Jemima Farrell | Massageraum 1 | 70 |

| Überlegen Sie Stibbons | Massageraum 1 | 70 |

| Burton Tracy | Massageraum 1 | 70 |

| Jack Smith | Massageraum 1 | 70 |

| Gast | Kürbisgericht | 35.0 |

| Gast | Kürbisgericht | 35.0 |

Antwort:

select mems . firstname || ' ' || mems . surname as member,

facs . name as facility,

case

when mems . memid = 0 then

bks . slots * facs . guestcost

else

bks . slots * facs . membercost

end as cost

from

cd . members mems

inner join cd . bookings bks

on mems . memid = bks . memid

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

where

bks . starttime >= ' 2012-09-14 ' and

bks . starttime < ' 2012-09-15 ' and (

( mems . memid = 0 and bks . slots * facs . guestcost > 30 ) or

( mems . memid != 0 and bks . slots * facs . membercost > 30 )

)

order by cost desc ; Dies ist ein bisschen kompliziert! Obwohl es eine komplexere Logik als zuvor verwendet hat, gibt es keine schreckliche Bemerkung. Die WHERE beschränkt unsere Ausgabe auf ausreichend kostspielige Zeilen am 09.09.2012 und erinnert sich daran, zwischen Gästen und anderen zu unterscheiden. Wir verwenden dann eine CASE in der Spaltenauswahl, um die richtigen Kosten für das Mitglied oder Gast auszugeben.

Wie können Sie eine Liste aller Mitglieder, einschließlich der Person ausgeben, die sie empfohlen hat (falls vorhanden), ohne Verknüpfungen zu verwenden? Stellen Sie sicher, dass in der Liste keine Duplikate vorhanden sind und dass jede Erstname + -nurname -Paarung als Spalte formatiert und geordnet ist.

Erwartete Ergebnisse:

| Mitglied | Empfohlen |

|---|---|

| Anna Mackenzie | Darren Smith |

| Anne Baker | Überlegen Sie Stibbons |

| Burton Tracy | |

| Charles Owen | Darren Smith |

| Darren Smith | |

| David Farrell | |

| David Jones | Janice Joplette |

| David Pinker | Jemima Farrell |

| Douglas Jones | David Jones |

| Erica Crumpet | Tracy Smith |

| Florence Bader | Überlegen Sie Stibbons |

| Gast | |

| Gerald Butters | Darren Smith |

| Henrietta Rumney | Matthew Genting |

| Henry Worthington-Smyth | Tracy Smith |

| Hyacinth Tupperware | |

| Jack Smith | Darren Smith |

| Janice Joplette | Darren Smith |

| Jemima Farrell | |

| Joan Coplin | Timothy Baker |

| John Hunt | Millicent -Zuständigkeitsbereich |

| Matthew Genting | Gerald Butters |

| Millicent -Zuständigkeitsbereich | Tracy Smith |

| Nancy Dare | Janice Joplette |

| Überlegen Sie Stibbons | Burton Tracy |

| Ramnaresh Sarwin | Florence Bader |

| Tim Boothe | Tim Rownam |

| Tim Rownam | |

| Timothy Baker | Jemima Farrell |

| Tracy Smith |

Antwort:

select distinct mems . firstname || ' ' || mems . surname as member,

( select recs . firstname || ' ' || recs . surname as recommender

from cd . members recs

where recs . memid = mems . recommendedby

)

from

cd . members mems

order by member; This exercise marks the introduction of subqueries. Subqueries are, as the name implies, queries within a query. They're commonly used with aggregates, to answer questions like 'get me all the details of the member who has spent the most hours on Tennis Court 1'.

In this case, we're simply using the subquery to emulate an outer join. For every value of member, the subquery is run once to find the name of the individual who recommended them (if any). A subquery that uses information from the outer query in this way (and thus has to be run for each row in the result set) is known as a correlated subquery .

The Produce a list of costly bookings exercise contained some messy logic: we had to calculate the booking cost in both the WHERE clause and the CASE statement. Try to simplify this calculation using subqueries. For reference, the question was:

How can you produce a list of bookings on the day of 2012-09-14 which will cost the member (or guest) more than $30? Remember that guests have different costs to members (the listed costs are per half-hour 'slot'), and the guest user is always ID 0. Include in your output the name of the facility, the name of the member formatted as a single column, and the cost. Order by descending cost.

Expected results:

| Mitglied | Einrichtung | kosten |

|---|---|---|

| GUEST GUEST | Massage Room 2 | 320 |

| GUEST GUEST | Massage Room 1 | 160 |

| GUEST GUEST | Massage Room 1 | 160 |

| GUEST GUEST | Massage Room 1 | 160 |

| GUEST GUEST | Tennis Court 2 | 150 |

| Jemima Farrell | Massage Room 1 | 140 |

| GUEST GUEST | Tennis Court 1 | 75 |

| GUEST GUEST | Tennis Court 2 | 75 |

| GUEST GUEST | Tennis Court 1 | 75 |

| Matthew Genting | Massage Room 1 | 70 |

| Florence Bader | Massage Room 2 | 70 |

| GUEST GUEST | Squash Court | 70.0 |

| Jemima Farrell | Massage Room 1 | 70 |

| Ponder Stibbons | Massage Room 1 | 70 |

| Burton Tracy | Massage Room 1 | 70 |

| Jack Smith | Massage Room 1 | 70 |

| GUEST GUEST | Squash Court | 35.0 |

| GUEST GUEST | Squash Court | 35.0 |

Antwort:

select member, facility, cost from (

select

mems . firstname || ' ' || mems . surname as member,

facs . name as facility,

case

when mems . memid = 0 then

bks . slots * facs . guestcost

else

bks . slots * facs . membercost

end as cost

from

cd . members mems

inner join cd . bookings bks

on mems . memid = bks . memid

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

where

bks . starttime >= ' 2012-09-14 ' and

bks . starttime < ' 2012-09-15 '

) as bookings

where cost > 30

order by cost desc ; This answer provides a mild simplification to the previous iteration: in the no-subquery version, we had to calculate the member or guest's cost in both the WHERE clause and the CASE statement. In our new version, we produce an inline query that calculates the total booking cost for us, allowing the outer query to simply select the bookings it's looking for. For reference, you may also see subqueries in the FROM clause referred to as inline views .

Querying data is all well and good, but at some point you're probably going to want to put data into your database! This section deals with inserting, updating, and deleting information. Operations that alter your data like this are collectively known as Data Manipulation Language, or DML.

In previous sections, we returned to you the results of the query you've performed. Since modifications like the ones we're making in this section don't return any query results, we instead show you the updated content of the table you're supposed to be working on. You can compare this with the table shown in 'Expected Results' to see how you've done.

If you struggle with these questions, I strongly recommend Learning SQL, by Alan Beaulieu.

The club is adding a new facility - a spa. We need to add it into the facilities table. Use the following values:

Expected results:

| facid | Name | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | Tischtennis | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Pool Table | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

| 9 | Spa | 20 | 30 | 100000 | 800 |

Antwort:

insert into cd . facilities

(facid, name, membercost, guestcost, initialoutlay, monthlymaintenance)

values ( 9 , ' Spa ' , 20 , 30 , 100000 , 800 ); INSERT INTO ... VALUES is the simplest way to insert data into a table. There's not a whole lot to discuss here: VALUES is used to construct a row of data, which the INSERT statement inserts into the table. It's a simple as that.

You can see that there's two sections in parentheses. The first is part of the INSERT statement, and specifies the columns that we're providing data for. The second is part of VALUES , and specifies the actual data we want to insert into each column.

If we're inserting data into every column of the table, as in this example, explicitly specifying the column names is optional. As long as you fill in data for all columns of the table, in the order they were defined when you created the table, you can do something like the following:

insert into cd . facilities values ( 9 , ' Spa ' , 20 , 30 , 100000 , 800 );Generally speaking, for SQL that's going to be reused I tend to prefer being explicit and specifying the column names.

In the previous exercise, you learned how to add a facility. Now you're going to add multiple facilities in one command. Use the following values:

Expected results:

| facid | Name | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | Tischtennis | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Pool Table | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

| 9 | Spa | 20 | 30 | 100000 | 800 |

| 10 | Squash Court 2 | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

Antwort:

insert into cd . facilities

(facid, name, membercost, guestcost, initialoutlay, monthlymaintenance)

values

( 9 , ' Spa ' , 20 , 30 , 100000 , 800 ),

( 10 , ' Squash Court 2 ' , 3 . 5 , 17 . 5 , 5000 , 80 ); VALUES can be used to generate more than one row to insert into a table, as seen in this example. Hopefully it's clear what's going on here: the output of VALUES is a table, and that table is copied into cd.facilities, the table specified in the INSERT command.

While you'll most commonly see VALUES when inserting data, Postgres allows you to use VALUES wherever you might use a SELECT . This makes sense: the output of both commands is a table, it's just that VALUES is a bit more ergonomic when working with constant data.

Similarly, it's possible to use SELECT wherever you see a VALUES . This means that you can INSERT the results of a SELECT . Zum Beispiel:

insert into cd . facilities

(facid, name, membercost, guestcost, initialoutlay, monthlymaintenance)

SELECT 9 , ' Spa ' , 20 , 30 , 100000 , 800

UNION ALL

SELECT 10 , ' Squash Court 2 ' , 3 . 5 , 17 . 5 , 5000 , 80 ; In later exercises you'll see us using INSERT ... SELECT to generate data to insert based on the information already in the database.

Let's try adding the spa to the facilities table again. This time, though, we want to automatically generate the value for the next facid, rather than specifying it as a constant. Use the following values for everything else:

Expected results:

| facid | Name | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | Tischtennis | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Pool Table | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

| 9 | Spa | 20 | 30 | 100000 | 800 |

Antwort:

insert into cd . facilities

(facid, name, membercost, guestcost, initialoutlay, monthlymaintenance)

select ( select max (facid) from cd . facilities ) + 1 , ' Spa ' , 20 , 30 , 100000 , 800 ; In the previous exercises we used VALUES to insert constant data into the facilities table. Here, though, we have a new requirement: a dynamically generated ID. This gives us a real quality of life improvement, as we don't have to manually work out what the current largest ID is: the SQL command does it for us.

Since the VALUES clause is only used to supply constant data, we need to replace it with a query instead. The SELECT statement is fairly simple: there's an inner subquery that works out the next facid based on the largest current id, and the rest is just constant data. The output of the statement is a row that we insert into the facilities table.

While this works fine in our simple example, it's not how you would generally implement an incrementing ID in the real world. Postgres provides SERIAL types that are auto-filled with the next ID when you insert a row. As well as saving us effort, these types are also safer: unlike the answer given in this exercise, there's no need to worry about concurrent operations generating the same ID.

We made a mistake when entering the data for the second tennis court. The initial outlay was 10000 rather than 8000: you need to alter the data to fix the error.

Expected results:

| facid | Name | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | Tischtennis | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Pool Table | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

Antwort:

update cd . facilities

set initialoutlay = 10000

where facid = 1 ; The UPDATE statement is used to alter existing data. If you're familiar with SELECT queries, it's pretty easy to read: the WHERE clause works in exactly the same fashion, allowing us to filter the set of rows we want to work with. These rows are then modified according to the specifications of the SET clause: in this case, setting the initial outlay.

The WHERE clause is extremely important. It's easy to get it wrong or even omit it, with disastrous results. Consider the following command:

update cd . facilities

set initialoutlay = 10000 ; There's no WHERE clause to filter for the rows we're interested in. The result of this is that the update runs on every row in the table! This is rarely what we want to happen.

We want to increase the price of the tennis courts for both members and guests. Update the costs to be 6 for members, and 30 for guests.

| facid | Name | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 6 | 30 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 6 | 30 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | Tischtennis | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Pool Table | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

Antwort:

update cd . facilities

set

membercost = 6 ,

guestcost = 30

where facid in ( 0 , 1 ); The SET clause accepts a comma separated list of values that you want to update.

We want to alter the price of the second tennis court so that it costs 10% more than the first one. Try to do this without using constant values for the prices, so that we can reuse the statement if we want to.

Expected results:

| facid | Name | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 5.5 | 27.5 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | Tischtennis | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Pool Table | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

Antwort:

update cd . facilities facs

set

membercost = ( select membercost * 1 . 1 from cd . facilities where facid = 0 ),

guestcost = ( select guestcost * 1 . 1 from cd . facilities where facid = 0 )

where facs . facid = 1 ; Updating columns based on calculated data is not too intrinsically difficult: we can do so pretty easily using subqueries. You can see this approach in our selected answer.

As the number of columns we want to update increases, standard SQL can start to get pretty awkward: you don't want to be specifying a separate subquery for each of 15 different column updates. Postgres provides a nonstandard extension to SQL called UPDATE...FROM that addresses this: it allows you to supply a FROM clause to generate values for use in the SET clause. Example below:

update cd . facilities facs

set

membercost = facs2 . membercost * 1 . 1 ,

guestcost = facs2 . guestcost * 1 . 1

from ( select * from cd . facilities where facid = 0 ) facs2

where facs . facid = 1 ;As part of a clearout of our database, we want to delete all bookings from the cd.bookings table. How can we accomplish this?

Expected results:

| bookid | facid | memid | starttime | slots |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Antwort:

delete from cd . bookings ; The DELETE statement does what it says on the tin: deletes rows from the table. Here, we show the command in its simplest form, with no qualifiers. In this case, it deletes everything from the table. Obviously, you should be careful with your deletes and make sure they're always limited - we'll see how to do that in the next exercise.

An alternative to unqualified DELETE s is the following:

truncate cd . bookings ; TRUNCATE also deletes everything in the table, but does so using a quicker underlying mechanism. It's not perfectly safe in all circumstances, though, so use judiciously. When in doubt, use DELETE .

We want to remove member 37, who has never made a booking, from our database. How can we achieve that?

Expected results:

| memid | Nachname | firstname | Adresse | PLZ | Telefon | Empfohlen von | joindate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | GAST | GAST | GAST | 0 | (000) 000-0000 | 2012-07-01 00:00:00 | |

| 1 | Schmied | Darren | 8 Bloomsbury Close, Boston | 4321 | 555-555-5555 | 2012-07-02 12:02:05 | |

| 2 | Schmied | Tracy | 8 Bloomsbury Close, New York | 4321 | 555-555-5555 | 2012-07-02 12:08:23 | |

| 3 | Rownam | Tim | 23 Highway Way, Boston | 23423 | (844) 693-0723 | 2012-07-03 09:32:15 | |

| 4 | Joplette | Janice | 20 Crossing Road, New York | 234 | (833) 942-4710 | 1 | 2012-07-03 10:25:05 |

| 5 | Butters | Gerald | 1065 Huntingdon Avenue, Boston | 56754 | (844) 078-4130 | 1 | 2012-07-09 10:44:09 |

| 6 | Tracy | Burton | 3 Tunisia Drive, Boston | 45678 | (822) 354-9973 | 2012-07-15 08:52:55 | |

| 7 | Wagen | Nancy | 6 Hunting Lodge Way, Boston | 10383 | (833) 776-4001 | 4 | 2012-07-25 08:59:12 |

| 8 | Boothe | Tim | 3 Bloomsbury Close, Reading, 00234 | 234 | (811) 433-2547 | 3 | 2012-07-25 16:02:35 |

| 9 | Stibbons | Ponder | 5 Dragons Way, Winchester | 87630 | (833) 160-3900 | 6 | 2012-07-25 17:09:05 |

| 10 | Owen | Charles | 52 Cheshire Grove, Winchester, 28563 | 28563 | (855) 542-5251 | 1 | 2012-08-03 19:42:37 |

| 11 | Jones | David | 976 Gnats Close, Reading | 33862 | (844) 536-8036 | 4 | 2012-08-06 16:32:55 |

| 12 | Bäcker | Anne | 55 Powdery Street, Boston | 80743 | 844-076-5141 | 9 | 2012-08-10 14:23:22 |

| 13 | Farrell | Jemima | 103 Firth Avenue, North Reading | 57392 | (855) 016-0163 | 2012-08-10 14:28:01 | |

| 14 | Schmied | Jack | 252 Binkington Way, Boston | 69302 | (822) 163-3254 | 1 | 2012-08-10 16:22:05 |

| 15 | Bader | Florenz | 264 Ursula Drive, Westford | 84923 | (833) 499-3527 | 9 | 2012-08-10 17:52:03 |

| 16 | Bäcker | Timothy | 329 James Street, Reading | 58393 | 833-941-0824 | 13 | 2012-08-15 10:34:25 |

| 17 | Pinker | David | 5 Impreza Road, Boston | 65332 | 811 409-6734 | 13 | 2012-08-16 11:32:47 |

| 20 | Genting | Matthew | 4 Nunnington Place, Wingfield, Boston | 52365 | (811) 972-1377 | 5 | 2012-08-19 14:55:55 |

| 21 | Mackenzie | Anna | 64 Perkington Lane, Reading | 64577 | (822) 661-2898 | 1 | 2012-08-26 09:32:05 |

| 22 | Coplin | Joan | 85 Bard Street, Bloomington, Boston | 43533 | (822) 499-2232 | 16 | 2012-08-29 08:32:41 |

| 24 | Sarwin | Ramnaresh | 12 Bullington Lane, Boston | 65464 | (822) 413-1470 | 15 | 2012-09-01 08:44:42 |

| 26 | Jones | Douglas | 976 Gnats Close, Reading | 11986 | 844 536-8036 | 11 | 2012-09-02 18:43:05 |

| 27 | Rumney | Henrietta | 3 Burkington Plaza, Boston | 78533 | (822) 989-8876 | 20 | 2012-09-05 08:42:35 |

| 28 | Farrell | David | 437 Granite Farm Road, Westford | 43532 | (855) 755-9876 | 2012-09-15 08:22:05 | |

| 29 | Worthington-Smyth | Henry | 55 Jagbi Way, North Reading | 97676 | (855) 894-3758 | 2 | 2012-09-17 12:27:15 |

| 30 | Aufgabe | Millicent | 641 Drudgery Close, Burnington, Boston | 34232 | (855) 941-9786 | 2 | 2012-09-18 19:04:01 |

| 33 | Tupperware | Hyazinthe | 33 Cheerful Plaza, Drake Road, Westford | 68666 | (822) 665-5327 | 2012-09-18 19:32:05 | |

| 35 | Jagd | John | 5 Bullington Lane, Boston | 54333 | (899) 720-6978 | 30 | 2012-09-19 11:32:45 |

| 36 | Crumpet | Erica | Crimson Road, North Reading | 75655 | (811) 732-4816 | 2 | 2012-09-22 08:36:38 |

Antwort:

delete from cd . members where memid = 37 ; This exercise is a small increment on our previous one. Instead of deleting all bookings, this time we want to be a bit more targeted, and delete a single member that has never made a booking. To do this, we simply have to add a WHERE clause to our command, specifying the member we want to delete. You can see the parallels with SELECT and UPDATE statements here.

There's one interesting wrinkle here. Try this command out, but substituting in member id 0 instead. This member has made many bookings, and you'll find that the delete fails with an error about a foreign key constraint violation. This is an important concept in relational databases, so let's explore a little further.

Foreign keys are a mechanism for defining relationships between columns of different tables. In our case we use them to specify that the memid column of the bookings table is related to the memid column of the members table. The relationship (or 'constraint') specifies that for a given booking, the member specified in the booking must exist in the members table. It's useful to have this guarantee enforced by the database: it means that code using the database can rely on the presence of the member. It's hard (even impossible) to enforce this at higher levels: concurrent operations can interfere and leave your database in a broken state.

PostgreSQL supports various different kinds of constraints that allow you to enforce structure upon your data. For more information on constraints, check out the PostgreSQL documentation on foreign keys

In our previous exercises, we deleted a specific member who had never made a booking. How can we make that more general, to delete all members who have never made a booking?

Expected results:

| memid | Nachname | firstname | Adresse | PLZ | Telefon | Empfohlen von | joindate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | GAST | GAST | GAST | 0 | (000) 000-0000 | 2012-07-01 00:00:00 | |

| 1 | Schmied | Darren | 8 Bloomsbury Close, Boston | 4321 | 555-555-5555 | 2012-07-02 12:02:05 | |

| 2 | Schmied | Tracy | 8 Bloomsbury Close, New York | 4321 | 555-555-5555 | 2012-07-02 12:08:23 | |

| 3 | Rownam | Tim | 23 Highway Way, Boston | 23423 | (844) 693-0723 | 2012-07-03 09:32:15 | |

| 4 | Joplette | Janice | 20 Crossing Road, New York | 234 | (833) 942-4710 | 1 | 2012-07-03 10:25:05 |

| 5 | Butters | Gerald | 1065 Huntingdon Avenue, Boston | 56754 | (844) 078-4130 | 1 | 2012-07-09 10:44:09 |

| 6 | Tracy | Burton | 3 Tunisia Drive, Boston | 45678 | (822) 354-9973 | 2012-07-15 08:52:55 | |

| 7 | Wagen | Nancy | 6 Hunting Lodge Way, Boston | 10383 | (833) 776-4001 | 4 | 2012-07-25 08:59:12 |

| 8 | Boothe | Tim | 3 Bloomsbury Close, Reading, 00234 | 234 | (811) 433-2547 | 3 | 2012-07-25 16:02:35 |

| 9 | Stibbons | Ponder | 5 Dragons Way, Winchester | 87630 | (833) 160-3900 | 6 | 2012-07-25 17:09:05 |

| 10 | Owen | Charles | 52 Cheshire Grove, Winchester, 28563 | 28563 | (855) 542-5251 | 1 | 2012-08-03 19:42:37 |

| 11 | Jones | David | 976 Gnats Close, Reading | 33862 | (844) 536-8036 | 4 | 2012-08-06 16:32:55 |

| 12 | Bäcker | Anne | 55 Powdery Street, Boston | 80743 | 844-076-5141 | 9 | 2012-08-10 14:23:22 |

| 13 | Farrell | Jemima | 103 Firth Avenue, North Reading | 57392 | (855) 016-0163 | 2012-08-10 14:28:01 | |

| 14 | Schmied | Jack | 252 Binkington Way, Boston | 69302 | (822) 163-3254 | 1 | 2012-08-10 16:22:05 |

| 15 | Bader | Florenz | 264 Ursula Drive, Westford | 84923 | (833) 499-3527 | 9 | 2012-08-10 17:52:03 |

| 16 | Bäcker | Timothy | 329 James Street, Reading | 58393 | 833-941-0824 | 13 | 2012-08-15 10:34:25 |

| 17 | Pinker | David | 5 Impreza Road, Boston | 65332 | 811 409-6734 | 13 | 2012-08-16 11:32:47 |

| 20 | Genting | Matthew | 4 Nunnington Place, Wingfield, Boston | 52365 | (811) 972-1377 | 5 | 2012-08-19 14:55:55 |

| 21 | Mackenzie | Anna | 64 Perkington Lane, Reading | 64577 | (822) 661-2898 | 1 | 2012-08-26 09:32:05 |

| 22 | Coplin | Joan | 85 Bard Street, Bloomington, Boston | 43533 | (822) 499-2232 | 16 | 2012-08-29 08:32:41 |

| 24 | Sarwin | Ramnaresh | 12 Bullington Lane, Boston | 65464 | (822) 413-1470 | 15 | 2012-09-01 08:44:42 |

| 26 | Jones | Douglas | 976 Gnats Close, Reading | 11986 | 844 536-8036 | 11 | 2012-09-02 18:43:05 |

| 27 | Rumney | Henrietta | 3 Burkington Plaza, Boston | 78533 | (822) 989-8876 | 20 | 2012-09-05 08:42:35 |

| 28 | Farrell | David | 437 Granite Farm Road, Westford | 43532 | (855) 755-9876 | 2012-09-15 08:22:05 | |

| 29 | Worthington-Smyth | Henry | 55 Jagbi Way, North Reading | 97676 | (855) 894-3758 | 2 | 2012-09-17 12:27:15 |

| 30 | Aufgabe | Millicent | 641 Drudgery Close, Burnington, Boston | 34232 | (855) 941-9786 | 2 | 2012-09-18 19:04:01 |

| 33 | Tupperware | Hyazinthe | 33 Cheerful Plaza, Drake Road, Westford | 68666 | (822) 665-5327 | 2012-09-18 19:32:05 | |

| 35 | Jagd | John | 5 Bullington Lane, Boston | 54333 | (899) 720-6978 | 30 | 2012-09-19 11:32:45 |

| 36 | Crumpet | Erica | Crimson Road, North Reading | 75655 | (811) 732-4816 | 2 | 2012-09-22 08:36:38 |

Antwort:

delete from cd . members where memid not in ( select memid from cd . bookings ); We can use subqueries to determine whether a row should be deleted or not. There's a couple of standard ways to do this. In our featured answer, the subquery produces a list of all the different member ids in the cd.bookings table. If a row in the table isn't in the list generated by the subquery, it gets deleted.

An alternative is to use a correlated subquery . Where our previous example runs a large subquery once, the correlated approach instead specifies a smaller subqueryto run against every row.

delete from cd . members mems where not exists ( select 1 from cd . bookings where memid = mems . memid );The two different forms can have different performance characteristics. Under the hood, your database engine is free to transform your query to execute it in a correlated or uncorrelated fashion, though, so things can be a little hard to predict.

Aggregation is one of those capabilities that really make you appreciate the power of relational database systems. It allows you to move beyond merely persisting your data, into the realm of asking truly interesting questions that can be used to inform decision making. This category covers aggregation at length, making use of standard grouping as well as more recent window functions.

If you struggle with these questions, I strongly recommend Learning SQL, by Alan Beaulieu and SQL Cookbook by Anthony Molinaro. In fact, get the latter anyway - it'll take you beyond anything you find on this site, and on multiple different database systems to boot.

For our first foray into aggregates, we're going to stick to something simple. We want to know how many facilities exist - simply produce a total count.

Expected results:

| zählen |

|---|

| 9 |

Antwort:

select count ( * ) from cd . facilities ; Aggregation starts out pretty simply! The SQL above selects everything from our facilities table, and then counts the number of rows in the result set. The count function has a variety of uses:

COUNT(*) simply returns the number of rowsCOUNT(address) counts the number of non-null addresses in the result set.COUNT(DISTINCT address) counts the number of different addresses in the facilities table. The basic idea of an aggregate function is that it takes in a column of data, performs some function upon it, and outputs a scalar (single) value. There are a bunch more aggregation functions, including MAX , MIN , SUM , and AVG . These all do pretty much what you'd expect from their names :-).

One aspect of aggregate functions that people often find confusing is in queries like the below:

select facid, count ( * ) from cd . facilitiesTry it out, and you'll find that it doesn't work. This is because count(*) wants to collapse the facilities table into a single value - unfortunately, it can't do that, because there's a lot of different facids in cd.facilities - Postgres doesn't know which facid to pair the count with.

Instead, if you wanted a query that returns all the facids along with a count on each row, you can break the aggregation out into a subquery as below:

select facid,

( select count ( * ) from cd . facilities )

from cd . facilitiesWhen we have a subquery that returns a scalar value like this, Postgres knows to simply repeat the value for every row in cd.facilities.

Produce a count of the number of facilities that have a cost to guests of 10 or more.

| zählen |

|---|

| 6 |

Antwort:

select count ( * ) from cd . facilities where guestcost >= 10 ; This one is only a simple modification to the previous question: we need to weed out the inexpensive facilities. This is easy to do using a WHERE clause. Our aggregation can now only see the expensive facilities.

Produce a count of the number of recommendations each member has made. Order by member ID.

Expected results:

| Empfohlen von | zählen |

|---|---|

| 1 | 5 |

| 2 | 3 |

| 3 | 1 |

| 4 | 2 |

| 5 | 1 |

| 6 | 1 |

| 9 | 2 |

| 11 | 1 |

| 13 | 2 |

| 15 | 1 |

| 16 | 1 |

| 20 | 1 |

| 30 | 1 |

Antwort:

select recommendedby, count ( * )

from cd . members

where recommendedby is not null

group by recommendedby

order by recommendedby; Previously, we've seen that aggregation functions are applied to a column of values, and convert them into an aggregated scalar value. This is useful, but we often find that we don't want just a single aggregated result: for example, instead of knowing the total amount of money the club has made this month, I might want to know how much money each different facility has made, or which times of day were most lucrative.

In order to support this kind of behaviour, SQL has the GROUP BY construct. What this does is batch the data together into groups, and run the aggregation function separately for each group. When you specify a GROUP BY , the database produces an aggregated value for each distinct value in the supplied columns. In this case, we're saying 'for each distinct value of recommendedby, get me the number of times that value appears'.

Produce a list of the total number of slots booked per facility. For now, just produce an output table consisting of facility id and slots, sorted by facility id.

Expected results:

| facid | Total Slots |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1320 |

| 1 | 1278 |

| 2 | 1209 |

| 3 | 830 |

| 4 | 1404 |

| 5 | 228 |

| 6 | 1104 |

| 7 | 908 |

| 8 | 911 |

Antwort:

select facid, sum (slots) as " Total Slots "

from cd . bookings

group by facid

order by facid; Other than the fact that we've introduced the SUM aggregate function, there's not a great deal to say about this exercise. For each distinct facility id, the SUM function adds together everything in the slots column.

Produce a list of the total number of slots booked per facility in the month of September 2012. Produce an output table consisting of facility id and slots, sorted by the number of slots.

Expected results:

| facid | Total Slots |

|---|---|

| 5 | 122 |

| 3 | 422 |

| 7 | 426 |

| 8 | 471 |

| 6 | 540 |

| 2 | 570 |

| 1 | 588 |

| 0 | 591 |

| 4 | 648 |

Antwort:

select facid, sum (slots) as " Total Slots "

from cd . bookings

where

starttime >= ' 2012-09-01 '

and starttime < ' 2012-10-01 '

group by facid

order by sum (slots); This is only a minor alteration of our previous example. Remember that aggregation happens after the WHERE clause is evaluated: we thus use the WHERE to restrict the data we aggregate over, and our aggregation only sees data from a single month.

Produce a list of the total number of slots booked per facility per month in the year of 2012. Produce an output table consisting of facility id and slots, sorted by the id and month.

Expected results:

| facid | Monat | Total Slots |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 7 | 270 |

| 0 | 8 | 459 |

| 0 | 9 | 591 |

| 1 | 7 | 207 |

| 1 | 8 | 483 |

| 1 | 9 | 588 |

| 2 | 7 | 180 |

| 2 | 8 | 459 |

| 2 | 9 | 570 |

| 3 | 7 | 104 |

| 3 | 8 | 304 |

| 3 | 9 | 422 |

| 4 | 7 | 264 |

| 4 | 8 | 492 |

| 4 | 9 | 648 |

| 5 | 7 | 24 |

| 5 | 8 | 82 |

| 5 | 9 | 122 |

| 6 | 7 | 164 |

| 6 | 8 | 400 |

| 6 | 9 | 540 |

| 7 | 7 | 156 |

| 7 | 8 | 326 |

| 7 | 9 | 426 |

| 8 | 7 | 117 |

| 8 | 8 | 322 |

| 8 | 9 | 471 |

Antwort:

select facid, extract(month from starttime) as month, sum (slots) as " Total Slots "

from cd . bookings

where

starttime >= ' 2012-01-01 '

and starttime < ' 2013-01-01 '

group by facid, month

order by facid, month; The main piece of new functionality in this question is the EXTRACT function. EXTRACT allows you to get individual components of a timestamp, like day, month, year, etc. We group by the output of this function to provide per-month values. An alternative, if we needed to distinguish between the same month in different years, is to make use of the DATE_TRUNC function, which truncates a date to a given granularity.

It's also worth noting that this is the first time we've truly made use of the ability to group by more than one column.

Find the total number of members who have made at least one booking.

Expected results:

| zählen |

|---|

| 30 |

Antwort:

select count (distinct memid) from cd . bookings Your first instinct may be to go for a subquery here. Something like the below:

select count ( * ) from

( select distinct memid from cd . bookings ) as mems This does work perfectly well, but we can simplify a touch with the help of a little extra knowledge in the form of COUNT DISTINCT . This does what you might expect, counting the distinct values in the passed column.

Produce a list of facilities with more than 1000 slots booked. Produce an output table consisting of facility id and hours, sorted by facility id.

Expected results:

| facid | Total Slots |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1320 |

| 1 | 1278 |

| 2 | 1209 |

| 4 | 1404 |

| 6 | 1104 |

Antwort:

select facid, sum (slots) as " Total Slots "

from cd . bookings

group by facid

having sum (slots) > 1000

order by facid It turns out that there's actually an SQL keyword designed to help with the filtering of output from aggregate functions. This keyword is HAVING .

The behaviour of HAVING is easily confused with that of WHERE . The best way to think about it is that in the context of a query with an aggregate function, WHERE is used to filter what data gets input into the aggregate function, while HAVING is used to filter the data once it is output from the function. Try experimenting to explore this difference!

Produce a list of facilities along with their total revenue. The output table should consist of facility name and revenue, sorted by revenue. Remember that there's a different cost for guests and members!

Expected results:

| Name | Einnahmen |

|---|---|

| Tischtennis | 180 |

| Snooker Table | 240 |

| Pool Table | 270 |

| Badminton Court | 1906.5 |

| Squash Court | 13468.0 |

| Tennis Court 1 | 13860 |

| Tennis Court 2 | 14310 |

| Massage Room 2 | 15810 |

| Massage Room 1 | 72540 |

Antwort:

select facs . name , sum (slots * case

when memid = 0 then facs . guestcost

else facs . membercost

end) as revenue

from cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

group by facs . name

order by revenue; The only real complexity in this query is that guests (member ID 0) have a different cost to everyone else. We use a case statement to produce the cost for each session, and then sum each of those sessions, grouped by facility.

Produce a list of facilities with a total revenue less than 1000. Produce an output table consisting of facility name and revenue, sorted by revenue. Remember that there's a different cost for guests and members!

Expected results:

| Name | Einnahmen |

|---|---|

| Tischtennis | 180 |

| Snooker Table | 240 |

| Pool Table | 270 |

Antwort:

select name, revenue from (

select facs . name , sum (case

when memid = 0 then slots * facs . guestcost

else slots * membercost

end) as revenue

from cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

group by facs . name

) as agg where revenue < 1000

order by revenue; You may well have tried to use the HAVING keyword we introduced in an earlier exercise, producing something like below:

select facs . name , sum (case

when memid = 0 then slots * facs . guestcost

else slots * membercost

end) as revenue

from cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

group by facs . name

having revenue < 1000

order by revenue; Unfortunately, this doesn't work! You'll get an error along the lines of ERROR: column "revenue" does not exist . Postgres, unlike some other RDBMSs like SQL Server and MySQL, doesn't support putting column names in the HAVING clause. This means that for this query to work, you'd have to produce something like below:

select facs . name , sum (case

when memid = 0 then slots * facs . guestcost

else slots * membercost

end) as revenue

from cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

group by facs . name

having sum (case

when memid = 0 then slots * facs . guestcost

else slots * membercost

end) < 1000

order by revenue; Having to repeat significant calculation code like this is messy, so our anointed solution instead just wraps the main query body as a subquery, and selects from it using a WHERE clause. In general, I recommend using HAVING for simple queries, as it increases clarity. Otherwise, this subquery approach is often easier to use.

Output the facility id that has the highest number of slots booked. For bonus points, try a version without a LIMIT clause. This version will probably look messy!

Expected results:

| facid | Total Slots |

|---|---|

| 4 | 1404 |

Antwort:

select facid, sum (slots) as " Total Slots "

from cd . bookings

group by facid

order by sum (slots) desc

LIMIT 1 ; Let's start off with what's arguably the simplest way to do this: produce a list of facility IDs and the total number of slots used, order by the total number of slots used, and pick only the top result.