これは、Alisdair OwenのPostgreSQL演習に関するすべての質問と回答の編集です。これらの問題を実際に解決すると、このガイドをスキミングするよりもさらに進むことができるので、訪問を必ず支払うようにしてください。

エクササイズを行うのは非常に簡単です。あなたがしなければならないのは、エクササイズを開いて、質問を見て、答えようとすることだけです!

これらの演習のデータセットは、新しく作成されたカントリークラブ向けで、メンバー、テニスコートなどの施設、およびそれらの施設の予約履歴があります。とりわけ、クラブは情報を使用して施設の使用/需要を分析する方法を理解したいと考えています。注:このデータセットは、興味深い一連のエクササイズをサポートするために純粋に設計されており、データベーススキーマにはいくつかの面で欠陥があります。優れたデザインの例として取得しないでください。メンバーのテーブルを見てみましょう。

CREATE TABLE cd .members

(

memid integer NOT NULL ,

surname character varying ( 200 ) NOT NULL ,

firstname character varying ( 200 ) NOT NULL ,

address character varying ( 300 ) NOT NULL ,

zipcode integer NOT NULL ,

telephone character varying ( 20 ) NOT NULL ,

recommendedby integer ,

joindate timestamp not null ,

CONSTRAINT members_pk PRIMARY KEY (memid),

CONSTRAINT fk_members_recommendedby FOREIGN KEY (recommendedby)

REFERENCES cd . members (memid) ON DELETE SET NULL

);各メンバーには、ID(シーケンシャルであることは保証されていません)、基本的なアドレス情報、それらを推奨するメンバーへの参照(もしあれば)、およびそれらが参加したときのタイムスタンプがあります。データセットのアドレスは、完全に(そして非現実的に)製造されています。

CREATE TABLE cd .facilities

(

facid integer NOT NULL ,

name character varying ( 100 ) NOT NULL ,

membercost numeric NOT NULL ,

guestcost numeric NOT NULL ,

initialoutlay numeric NOT NULL ,

monthlymaintenance numeric NOT NULL ,

CONSTRAINT facilities_pk PRIMARY KEY (facid)

);施設のテーブルには、カントリークラブが持っているすべての予約可能な施設がリストされています。クラブには、ID/名前情報、メンバーとゲストの両方の予約コスト、施設の建設の初期コスト、および推定毎月の維持費が保存されています。彼らは、この情報を使用して、各施設がどれほど財政的に価値があるかを追跡したいと考えています。

CREATE TABLE cd .bookings

(

bookid integer NOT NULL ,

facid integer NOT NULL ,

memid integer NOT NULL ,

starttime timestamp NOT NULL ,

slots integer NOT NULL ,

CONSTRAINT bookings_pk PRIMARY KEY (bookid),

CONSTRAINT fk_bookings_facid FOREIGN KEY (facid) REFERENCES cd . facilities (facid),

CONSTRAINT fk_bookings_memid FOREIGN KEY (memid) REFERENCES cd . members (memid)

);最後に、施設の予約を追跡するテーブルがあります。これにより、施設ID、予約を行ったメンバー、予約の開始、予約が行われた30分の「スロット」があります。この特異なデザインは、特定のクエリをより困難にしますが、いくつかの興味深い課題を提供する必要があります。

さて、それはあなたが必要とするすべての情報でなければなりません。上記のメニューから試すために、クエリのカテゴリを選択するか、または最初から開始することもできます。

問題ない!起きて実行することはそれほど難しくありません。まず、PostgreSQLのインストールが必要です。これをここから入手できます。開始したら、SQLをダウンロードします。

最後に、 psql -U <username> -f clubdata.sql -d postgres -x -qを実行して「エクササイズ」データベースを作成します。ポストグレス「pgexercise」ユーザー、テーブル、データをロードします。 Cロケールを使用します)

クエリを実行しているときは、PSQLが少し不格好だと感じるかもしれません。その場合、PGADMINまたはEclipseデータベース開発ツールを試すことをお勧めします。

このカテゴリは、SQLの基本を扱います。それは、選択と条項、ケース表現、組合、および他のいくつかのオッズと終わりをカバーします。すでにSQLで教育を受けている場合は、おそらくこれらの演習がかなり簡単だと思うでしょう。そうでない場合は、今後のより困難なカテゴリの学習を開始するための適切なポイントを見つける必要があります!

これらの質問に苦労している場合は、Alan BeaulieuのSQLを、このテーマに関する簡潔でよく書かれた本として学習することを強くお勧めします。データベースシステムの基礎に興味がある場合(それらの使用方法とは対照的に)、CJ日付までのデータベースシステムの紹介も調査する必要があります。

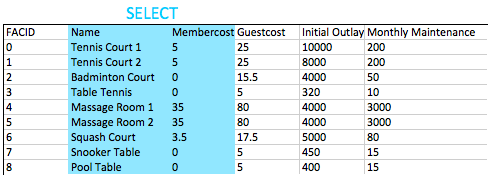

CD.Facitiesテーブルからすべての情報をどのように取得できますか?

期待される結果:

| facid | 名前 | メンバーコスト | GuestCost | InitialOutlay | 毎月のメンテナンス |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | テニスコート1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | テニスコート2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | バドミントン裁判所 | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | 卓球 | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | マッサージルーム1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | マッサージルーム2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | スカッシュコート | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | スヌーカーテーブル | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | ビリヤード台 | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

答え:

select * from cd . facilities ; SELECTステートメントは、データベースから情報を読み取るクエリの基本的な開始ブロックです。通常、最小選択ステートメントはselect [some set of columns] from [some table or group of tables]で構成されています。

この場合、施設テーブルからすべての情報が必要です。 From Sectionは簡単です - cd.facilitiesテーブルを指定するだけです。 「CD」はテーブルのスキーマです。これは、データベース内の関連情報の論理的なグループ化に使用される用語です。

次に、すべての列が必要であることを指定する必要があります。便利なことに、「すべての列」 - *の速記があります。すべての列名を骨の折れる代わりに、これを使用できます。

すべての施設のリストとその費用をメンバーに印刷したいと思います。施設の名前とコストのみのリストをどのように取得しますか?

期待される結果:

| 名前 | メンバーコスト |

|---|---|

| テニスコート1 | 5 |

| テニスコート2 | 5 |

| バドミントン裁判所 | 0 |

| 卓球 | 0 |

| マッサージルーム1 | 35 |

| マッサージルーム2 | 35 |

| スカッシュコート | 3.5 |

| スヌーカーテーブル | 0 |

| ビリヤード台 | 0 |

答え:

select name, membercost from cd . facilities ; この質問では、必要な列を指定する必要があります。 SELECTステートメントに指定された列名の単純なコンマ区切りリストでそれを行うことができます。以下に示すように、すべてのデータベースが句で使用できる列を見ることと、要求した列を返します。

一般的に言えば、非投影クエリの場合、 *を使用するのではなく、クエリに必要な列の名前を指定することが望ましいと考えられています。これは、より多くの列がテーブルに追加された場合、アプリケーションが対処できない可能性があるためです。

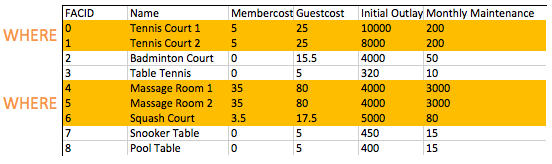

メンバーに料金を請求する施設のリストをどのように作成できますか?

期待される結果:

| facid | 名前 | メンバーコスト | GuestCost | InitialOutlay | 毎月のメンテナンス |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | テニスコート1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | テニスコート2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 4 | マッサージルーム1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | マッサージルーム2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | スカッシュコート | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

答え:

select * from cd . facilities where membercost > 0 ; FROM句は、結果を読むために一連の候補行を構築するために使用されます。これまでの例では、この行のセットは単にテーブルの内容でした。将来的には、より興味深い候補者を作成できるようにする参加を探索します。

候補の行のセットを作成したら、 WHERE句を使用すると、興味のある行、この場合はメンバーコストがゼロ以上の行をフィルタリングできます。後の演習でわかるように、 WHEREにはブールロジックと複数のコンポーネントが組み合わされていることがあります。たとえば、0を超えるコストと10未満のコストで施設WHERE検索することが可能です。

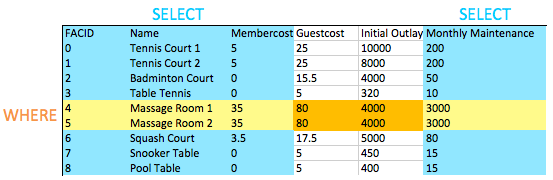

メンバーに料金を請求する施設のリストをどのように作成できますか?その料金は毎月のメンテナンスコストの1/50未満ですか?問題の施設のFACID、施設名、会員費用、および毎月のメンテナンスを返却してください。

期待される結果:

| facid | 名前 | メンバーコスト | 毎月のメンテナンス |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | マッサージルーム1 | 35 | 3000 |

| 5 | マッサージルーム2 | 35 | 3000 |

答え:

select facid, name, membercost, monthlymaintenance

from cd . facilities

where

membercost > 0 and

(membercost < monthlymaintenance / 50 . 0 ); WHEREは、私たちが興味を持っている行のフィルタリングを可能にすることができます - この場合、メンバーコストがゼロを超え、毎月のメンテナンスコストの1/50未満の人。ご覧のとおり、マッサージルームは人材派遣コストのおかげで非常に高価です!

2つ以上の条件をテストしたい場合は、それらを使用しAND結合します。予想通り、使用するORテストすることができます。

これが、 WHERE句と特定の列の選択を組み合わせた最初のクエリであることに気付いたかもしれません。これの効果の下の画像で見ることができます。選択した列と選択した行の交差点により、返されるデータが得られます。これは今ではあまり面白くないかもしれませんが、後で結合するようなより複雑な操作を追加すると、この動作の単純な優雅さがわかります。

「テニス」という言葉を名前にして、すべての施設のリストをどのように作成できますか?

期待される結果:

| facid | 名前 | メンバーコスト | GuestCost | InitialOutlay | 毎月のメンテナンス |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | テニスコート1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | テニスコート2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 3 | 卓球 | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

答え:

select *

from cd . facilities

where

name like ' %Tennis% ' ; SQLのLIKEオペレーターは、文字列にシンプルなパターンマッチングを提供します。それは非常に普遍的に実装されており、使いやすく、簡単に使用できます。任意の文字列に一致し、_単一の文字に一致する_を持つ文字列が必要です。この場合、「テニス」という単語を含む名前を探しているので、どちらの側にも%を置くことは法案に適合します。

このタスクを達成する他の方法があります。たとえば、Postgresは〜演算子との正規表現をサポートしています。快適に感じるものは何でも使用しますが、システム間ではるかにポータブルであるLIKE演算子がはるかにポータブルであることに注意してください。

ID 1と5の施設の詳細をどのように取得できますか?またはオペレーターを使用せずに行うようにしてください。

期待される結果:

| facid | 名前 | メンバーコスト | GuestCost | InitialOutlay | 毎月のメンテナンス |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | テニスコート2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 5 | マッサージルーム2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

答え:

select *

from cd . facilities

where

facid in ( 1 , 5 ); この質問に対する明らかな答えはwhere facid = 1 or facid = 5ように見えるWHEREを使用することです。多数の可能性のある一致で簡単な代替案は、 INです。 INオペレーターは、可能な値のリストを取得し、(この場合)FACIDと一致します。値の1つが一致する場合、句はその行に対して真であり、行が返されます。

IN Operatorは、リレーショナルモデルの優雅さの優れた初期のデモンストレーターです。それが取る議論は、単なる値のリストではありません - 実際には単一の列を持つテーブルです。クエリもテーブルを返すため、単一の列を返すクエリを作成する場合、それらの結果をINに送ることができます。おもちゃを与えるために:

select *

from cd . facilities

where

facid in (

select facid from cd . facilities

);この例は、すべての施設を選択するだけで機能的に同等ですが、あるクエリの結果を別のクエリに供給する方法を示します。内部クエリはサブクエリと呼ばれます。

毎月のメンテナンスコストが100ドルを超えるかどうかに応じて、それぞれが「安い」または「高価」とラベル付けされている施設のリストをどのように作成できますか?問題の施設の名前と毎月のメンテナンスを返します。

期待される結果:

| 名前 | 料金 |

|---|---|

| テニスコート1 | 高い |

| テニスコート2 | 高い |

| バドミントン裁判所 | 安い |

| 卓球 | 安い |

| マッサージルーム1 | 高い |

| マッサージルーム2 | 高い |

| スカッシュコート | 安い |

| スヌーカーテーブル | 安い |

| ビリヤード台 | 安い |

答え:

select name,

case when (monthlymaintenance > 100 ) then

' expensive '

else

' cheap '

end as cost

from cd . facilities ; この演習には、いくつかの新しい概念が含まれています。 1つ目は、 SELECTとFROM間のクエリの領域で計算を行っているという事実です。以前は、これを使用して返品したい列のみを選択していましたが、サブクエリを含む、返された行ごとに単一の結果を生成するものをここに置くことができます。

2番目の新しい概念は、 CASEステートメント自体です。 CASE 、クエリに示されているフォームを使用して、他の言語のif/switchステートメントと効果的に似ています。 「中間」オプションを追加するために、いつ別のwhen...thenを挿入します。

最後に、 ASオペレーターがあります。これは、列または表現のラベルを付けるために単に使用され、それらをより適切に表示するか、サブクエリの一部として使用すると参照しやすくするために使用されます。

2012年9月の開始後に参加したメンバーのリストをどのように作成できますか?問題のメンバーのmemid、surname、firstName、およびJoindateを返します。

期待される結果:

| memid | 姓 | ファーストネーム | ジョインド |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | サーウィン | Ramnaresh | 2012-09-01 08:44:42 |

| 26 | ジョーンズ | ダグラス | 2012-09-02 18:43:05 |

| 27 | ラミー | ヘンリエッタ | 2012-09-05 08:42:35 |

| 28 | ファレル | デビッド | 2012-09-15 08:22:05 |

| 29 | ワージントンスミス | ヘンリー | 2012-09-17 12:27:15 |

| 30 | purview | ミリセント | 2012-09-18 19:04:01 |

| 33 | タッパーウェア | ヒヤシンス | 2012-09-18 19:32:05 |

| 35 | ハント | ジョン | 2012-09-19 11:32:45 |

| 36 | クランペット | エリカ | 2012-09-22 08:36:38 |

| 37 | スミス | ダレン | 2012-09-26 18:08:45 |

答え:

select memid, surname, firstname, joindate

from cd . members

where joindate >= ' 2012-09-01 ' ; これは、SQLタイムスタンプの最初の外観です。それらは、下降順にフォーマットされています: YYYY-MM-DD HH:MM:SS.nnnnnn 。日付間の違いを得ることはもう少し関与していますが(そして強力です!)、Unixタイムスタンプと同じように比較できます。この場合、タイムスタンプの日付部分を指定しました。これは、Postgresによって完全なタイムスタンプ2012-09-01 00:00:00に自動的にキャストされます。

メンバーテーブルに最初の10姓の注文されたリストをどのように作成できますか?リストには複製を含めてはなりません。

期待される結果:

| 姓 |

|---|

| より悪い |

| ベイカー |

| ブース |

| バター |

| コプリン |

| クランペット |

| あえて |

| ファレル |

| ゲスト |

| 紳士 |

答え:

select distinct surname

from cd . members

order by surname

limit 10 ; ここには3つの新しい概念がありますが、それらはすべて非常に簡単です。

SELECT後にDISTINCT指定は、結果セットから重複する行を削除します。これは行に適用されることに注意してください。行Aに複数の列がある場合、行Bはすべての列の値が同じ場合にのみ等しくなります。一般的なルールとして、意志のあるファッションでDISTINCT使用を使用しないでください - 大規模なクエリ結果セットから重複を削除することは自由ではないので、必要に応じて行います。FROMの後とWHERE ) ORDER BYを指定すると、列または列のセット(コンマ分離)で結果を順序付けることができます。LIMITキーワードを使用すると、取得した結果の数を制限できます。これは、結果のページを一度に入手するのに役立ち、 OFFSETキーワードと組み合わせて次のページを取得できます。これはMySQLで使用されているのと同じアプローチであり、非常に便利です - 残念ながら、このプロセスは他のDBSではもう少し複雑であることがわかります。何らかの理由で、すべての姓とすべての施設名の複合リストが必要です。はい、これは不自然な例です:-)。そのリストを作成します!

期待される結果:

| 姓 |

|---|

| テニスコート2 |

| ワージントンスミス |

| バドミントン裁判所 |

| ピンカー |

| あえて |

| より悪い |

| マッケンジー |

| クランペット |

| マッサージルーム1 |

| スカッシュコート |

答え:

select surname

from cd . members

union

select name

from cd . facilities ; UNIONオペレーターは、予想されることを行います。2つのSQLクエリの結果を1つのテーブルに組み合わせます。警告は、2つのクエリの両方の結果の両方が同じ数の列と互換性のあるデータ型を持っている必要があることです。

UNION重複する行を削除しますが、 UNION ALLそうではありません。重複した結果を気にしない限り、デフォルトでUNION ALLデフォルトで使用します。

最後のメンバーのサインアップ日を取得したいと思います。この情報をどのように取得できますか?

期待される結果:

| 最新 |

|---|

| 2012-09-26 18:08:45 |

答え:

select max (joindate) as latest

from cd . members ; これは、SQLの集計関数への最初の進出です。それらは、行のグループ全体に関する情報を抽出し、次のような質問を簡単に尋ねるために使用されます。

ここでの最大集約関数は非常に単純です。Joindateのすべての可能な値を受信し、最大の値を出力します。関数を集約するためのより多くの力がありますが、将来の演習で出会うことになります。

日付だけでなく、サインアップした最後のメンバーの最初と姓を取得したいと思います。どうすればできますか?

期待される結果:

| ファーストネーム | 姓 | ジョインド |

|---|---|---|

| ダレン | スミス | 2012-09-26 18:08:45 |

答え:

select firstname, surname, joindate

from cd . members

where joindate =

( select max (joindate)

from cd . members ); 上記の提案されたアプローチでは、サブクエリを使用して、最新のJoindateが何であるかを調べます。このサブクエリは、スカラーテーブル、つまり、単一の列と単一の行を備えたテーブルを返します。単一の値しかないので、単一の一定の値を置く可能性のある場所にサブクエリを置き換えることができます。この場合、それを使用して、特定のメンバーを見つけるためにWHEREの句句を完成させます。

あなたは以下のようなことができることを願っています:

select firstname, surname, max (joindate)

from cd . members残念ながら、これはうまくいきません。 MAX関数は、 WHEREのような行を制限しません - それは単に多くの価値を取り入れ、最大の値を返します。次に、データベースは、名前の長いリストを最大関数から出てくる単一の参加日をペアリングする方法を疑問にしておきます。代わりに、「最大参加日と同じ参加日がある行を見つけてください」と言わなければなりません。

ヒントが述べたように、この仕事を成し遂げる他の方法があります - 一例は以下にあります。このアプローチでは、最後の参加日が何であるかを明示的に見つけるのではなく、参加日を下ってメンバーテーブルを注文し、最初のテーブルを選択します。このアプローチは、まったく同時に参加する2人の非常にありそうもない不測の事態をカバーしていないことに注意してください:-)。

select firstname, surname, joindate

from cd . members

order by joindate desc

limit 1 ;このカテゴリは、主にリレーショナルデータベースシステムの基本的な概念を扱います。結合。結合することで、複数のテーブルから関連情報を組み合わせて質問に答えることができます。これは、クエリの容易さに有益であるだけではありません。結合能力の欠如は、データの非規制を促進し、データを内部的に一貫性を保つ複雑さを高めます。

このトピックは、内側、外側、および自己結合をカバーし、サブクリーリー(クエリ内のクエリ)に少し時間を費やします。これらの質問に苦労している場合は、Alan BeaulieuのSQLを、このテーマに関する簡潔でよく書かれた本として学習することを強くお勧めします。

「David Farrell」という名前のメンバーによる予約の開始時間のリストをどのように作成できますか?

期待される結果:

| 開始時刻 |

|---|

| 2012-09-18 09:00:00 |

| 2012-09-18 17:30:00 |

| 2012-09-18 13:30:00 |

| 2012-09-18 20:00:00 |

| 2012-09-19 09:30:00 |

| 2012-09-19 15:00:00 |

| 2012-09-19 12:00:00 |

| 2012-09-20 15:30:00 |

| 2012-09-20 11:30:00 |

| 2012-09-20 14:00:00 |

答え:

select bks . starttime

from

cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . members mems

on mems . memid = bks . memid

where

mems . firstname = ' David '

and mems . surname = ' Farrell ' ; 最も一般的に使用される一種の結合はINNER JOINです。これが行うことは、結合式に基づいて2つのテーブルを組み合わせることです。この場合、メンバーテーブルの各メンバーIDについて、予約テーブルの一致する値を探しています。一致が見つかる場所では、各テーブルの値を組み合わせた行が返されます。各テーブルにエイリアス(BKSとMEMS)を与えたことに注意してください。これは2つの理由で使用されます。1つ目は便利であり、次に同じテーブルに何度か参加し、テーブルが結合された各時間と列を区別する必要があります。

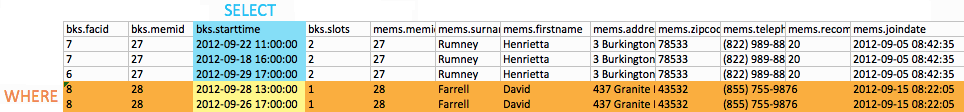

私たちの選択と今のところ条項を無視し、 FROM Statementが生み出しているものに焦点を当てましょう。以前のすべての例では、 FROM単純なテーブルでした。今は何ですか?別のテーブル!今回は、予約とメンバーの複合として制作されています。以下の結合の出力のサブセットを見ることができます。

メンバーテーブルの各メンバーについて、Joinは予約テーブルのすべてのマッチングメンバーIDを見つけました。その後、各試合で、メンバーテーブルの行と予約テーブルから行を組み合わせた行を作成しました。

明らかに、これはそれ自体があまりにも多くの情報であり、有用な質問はそれを除外したいと思うでしょう。クエリでは、以下に示すように、 SELECT句の開始を使用して列を選択し、列を選択してWHEREを選択します。

デビッドの予約を見つけるために必要なのはそれだけです!一般的に、 FROM句の出力は本質的に1つの大きなテーブルであり、その後情報をフィルタリングすることを覚えておくことをお勧めします。これは非効率的に聞こえるかもしれませんが、心配しないでください、カバーの下では、DBはよりインテリジェントに動作します:-)。

最後の注:内側結合には2つの異なる構文があります。私が好むものをあなたに示しました、私は他の結合タイプとより一致していると思うことを示しました。一般に、以下に示す別の構文が表示されます。

select bks . starttime

from

cd . bookings bks,

cd . members mems

where

mems . firstname = ' David '

and mems . surname = ' Farrell '

and mems . memid = bks . memid ;これは、機能的には承認された答えとまったく同じです。この構文をより快適に感じる場合は、お気軽に使用してください!

日付「2012-09-21」のテニスコートの予約の開始時間のリストをどのように作成できますか?開始時間と施設名のペアリングのリストを返し、時間ごとに注文します。

期待される結果:

| 始める | 名前 |

|---|---|

| 2012-09-21 08:00:00 | テニスコート1 |

| 2012-09-21 08:00:00 | テニスコート2 |

| 2012-09-21 09:30:00 | テニスコート1 |

| 2012-09-21 10:00:00 | テニスコート2 |

| 2012-09-21 11:30:00 | テニスコート2 |

| 2012-09-21 12:00:00 | テニスコート1 |

| 2012-09-21 13:30:00 | テニスコート1 |

| 2012-09-21 14:00:00 | テニスコート2 |

| 2012-09-21 15:30:00 | テニスコート1 |

| 2012-09-21 16:00:00 | テニスコート2 |

| 2012-09-21 17:00:00 | テニスコート1 |

| 2012-09-21 18:00:00 | テニスコート2 |

答え:

select bks . starttime as start, facs . name as name

from

cd . facilities facs

inner join cd . bookings bks

on facs . facid = bks . facid

where

facs . facid in ( 0 , 1 ) and

bks . starttime >= ' 2012-09-21 ' and

bks . starttime < ' 2012-09-22 '

order by bks . starttime ; これは別のINNER JOINクエリですが、それはかなり複雑です!クエリのFROMから簡単です - 私たちは単にFACIDで施設と予約のテーブルに一緒に参加しています。これにより、予約の各行について、予約されている施設に関する詳細な情報を添付したテーブルが生成されます。

WHEREのコンポーネントに。開始時刻のチェックはかなり自明です - すべての予約が指定された日付間で開始されることを確認しています。私たちはテニスコートのみに関心があるため、 INオペレーターを使用して、データベースシステムに施設ID 0または1のみを返すように指示します - 裁判所のIDです。これを表現する他の方法があります: where facs.facid = 0 or facs.facid = 1 、またはwhere facs.name like 'Tennis%'でも、facs.facid = 0またはfacs.facid = 1を使用できたのです。

残りは非常にシンプルです。興味のある列SELECT 、開始時間ORDER BY 。

別のメンバーを推薦したすべてのメンバーのリストをどのように出力できますか?リストに重複がないことを確認し、その結果が(姓、FirstName)によって注文されていることを確認してください。

期待される結果:

| ファーストネーム | 姓 |

|---|---|

| フィレンツェ | より悪い |

| ティモシー | ベイカー |

| ジェラルド | バター |

| ジェミマ | ファレル |

| マシュー | 紳士 |

| デビッド | ジョーンズ |

| ジャニス | ジョプレット |

| ミリセント | purview |

| ティム | Rownam |

| ダレン | スミス |

| トレーシー | スミス |

| 熟考 | スティボン |

| バートン | トレーシー |

答え:

select distinct recs . firstname as firstname, recs . surname as surname

from

cd . members mems

inner join cd . members recs

on recs . memid = mems . recommendedby

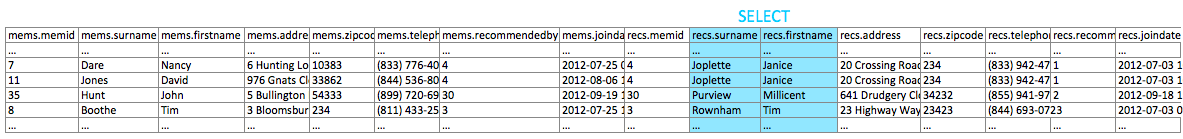

order by surname, firstname; 一部の人々が混乱を感じる概念は次のとおりです。あなたはそれ自体にテーブルに参加できます!これは、Cd.membersの推奨されるものと同様に、同じ表にデータを参照する列がある場合に非常に便利です。

これを視覚化するのに苦労している場合は、これが他の内側の結合と同じように機能することを忘れないでください。私たちの参加は、推奨される値を持つメンバーの各行を取り、一致するメンバーIDを持つ行を再びメンバーを探します。次に、2つのメンバーエントリを組み合わせた出力行を生成します。これは以下の図のように見えます:

出力セットに2つの「姓」列があるかもしれませんが、テーブルエイリアスで区別できることに注意してください。希望する列を選択したら、 DISTINCTを使用して、重複がないことを確認します。

推奨する個人を含むすべてのメンバーのリストをどのように出力できますか?結果が(姓、firstName)で注文されることを確認してください。

期待される結果:

| memfname | memsname | recfname | recsname |

|---|---|---|---|

| フィレンツェ | より悪い | 熟考 | スティボン |

| アン | ベイカー | 熟考 | スティボン |

| ティモシー | ベイカー | ジェミマ | ファレル |

| ティム | ブース | ティム | Rownam |

| ジェラルド | バター | ダレン | スミス |

| ジョーン | コプリン | ティモシー | ベイカー |

| エリカ | クランペット | トレーシー | スミス |

| ナンシー | あえて | ジャニス | ジョプレット |

| デビッド | ファレル | ||

| ジェミマ | ファレル | ||

| ゲスト | ゲスト | ||

| マシュー | 紳士 | ジェラルド | バター |

| ジョン | ハント | ミリセント | purview |

| デビッド | ジョーンズ | ジャニス | ジョプレット |

| ダグラス | ジョーンズ | デビッド | ジョーンズ |

| ジャニス | ジョプレット | ダレン | スミス |

| アンナ | マッケンジー | ダレン | スミス |

| チャールズ | オーウェン | ダレン | スミス |

| デビッド | ピンカー | ジェミマ | ファレル |

| ミリセント | purview | トレーシー | スミス |

| ティム | Rownam | ||

| ヘンリエッタ | ラミー | マシュー | 紳士 |

| Ramnaresh | サーウィン | フィレンツェ | より悪い |

| ダレン | スミス | ||

| ダレン | スミス | ||

| ジャック | スミス | ダレン | スミス |

| トレーシー | スミス | ||

| 熟考 | スティボン | バートン | トレーシー |

| バートン | トレーシー | ||

| ヒヤシンス | タッパーウェア | ||

| ヘンリー | ワージントンスミス | トレーシー | スミス |

答え:

select mems . firstname as memfname, mems . surname as memsname, recs . firstname as recfname, recs . surname as recsname

from

cd . members mems

left outer join cd . members recs

on recs . memid = mems . recommendedby

order by memsname, memfname; 別の新しい概念を紹介しましょう: LEFT OUTER JOIN 。これらは、内側の結合とは異なる方法によって最もよく説明されています。内側の結合は、左と右のテーブルを取り、結合条件( ON )に基づいて一致する行を探します。条件が満たされると、結合された行が生成されます。 LEFT OUTER JOIN同様に動作しますが、左手テーブルの特定の行が何も一致しない場合でも、出力行が生成されます。その出力行は、左手のテーブルの列と、右手のテーブル列の代わりにたくさんのNULLSで構成されています。

これは、この質問のような状況で役立ちます。この質問では、オプションのデータを使用して出力を生成したいと考えています。私たちはすべてのメンバーの名前と、その人が存在する場合は彼らの推薦者の名前を望んでいます。内側の結合でそれを適切に表現することはできません。

ご想像のとおり、他の外側の結合もあります。 RIGHT OUTER JOIN 、式の左側がオプションのデータを含むものであることを除いて、 LEFT OUTER JOINによく似ています。まれに使用されていないFULL OUTER JOIN式の両側をオプションとして扱います。

テニスコートを使用したすべてのメンバーのリストをどのように作成できますか?あなたの出力に裁判所の名前を含め、メンバーの名前は単一の列としてフォーマットされています。複製データがないことを確認し、メンバー名で注文します。

期待される結果:

| メンバー | 施設 |

|---|---|

| アン・ベイカー | テニスコート2 |

| アン・ベイカー | テニスコート1 |

| バートン・トレーシー | テニスコート2 |

| バートン・トレーシー | テニスコート1 |

| チャールズオーウェン | テニスコート2 |

| チャールズオーウェン | テニスコート1 |

| ダレン・スミス | テニスコート2 |

| デビッド・ファレル | テニスコート2 |

| デビッド・ファレル | テニスコート1 |

| デビッド・ジョーンズ | テニスコート1 |

| デビッド・ジョーンズ | テニスコート2 |

| デビッド・ピンカー | テニスコート1 |

| ダグラス・ジョーンズ | テニスコート1 |

| エリカ・クランペット | テニスコート1 |

| フローレンス・バダー | テニスコート1 |

| フローレンス・バダー | テニスコート2 |

| ゲスト | テニスコート2 |

| ゲスト | テニスコート1 |

| ジェラルドバター | テニスコート1 |

| ジェラルドバター | テニスコート2 |

| ヘンリエッタ・ラニー | テニスコート2 |

| ジャック・スミス | テニスコート1 |

| ジャック・スミス | テニスコート2 |

| ジャニス・ジョプレット | テニスコート1 |

| ジャニス・ジョプレット | テニスコート2 |

| ジェミマ・ファレル | テニスコート2 |

| ジェミマ・ファレル | テニスコート1 |

| ジョーン・コプリン | テニスコート1 |

| ジョン・ハント | テニスコート1 |

| ジョン・ハント | テニスコート2 |

| マシュー・ゲンティン | テニスコート1 |

| ミリセントパビュー | テニスコート2 |

| ナンシー・デア | テニスコート2 |

| ナンシー・デア | テニスコート1 |

| 熟考するスティボン | テニスコート2 |

| 熟考するスティボン | テニスコート1 |

| Ramnaresh Sarwin | テニスコート2 |

| Ramnaresh Sarwin | テニスコート1 |

| ティムブース | テニスコート1 |

| ティムブース | テニスコート2 |

| ティム・ロウネム | テニスコート1 |

| ティム・ロウネム | テニスコート2 |

| ティモシー・ベイカー | テニスコート2 |

| ティモシー・ベイカー | テニスコート1 |

| トレーシー・スミス | テニスコート2 |

| トレーシー・スミス | テニスコート1 |

答え:

select distinct mems . firstname || ' ' || mems . surname as member, facs . name as facility

from

cd . members mems

inner join cd . bookings bks

on mems . memid = bks . memid

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

where

bks . facid in ( 0 , 1 )

order by member この演習は、主に以前の質問で学んだことのより複雑なアプリケーションです。また、複数の参加を使用したのは初めてです。これは、一部の人にとっては少し混乱するかもしれません。結合式を読むとき、結合は効果的に2つのテーブルを取る関数であり、1つは左のテーブルにラベル付けされ、もう1つは右側にラベルを付けることに注意してください。これは、クエリに1つだけ結合するだけで視覚化するのが簡単ですが、2つとはもう少し混乱しています。

このクエリでの2番目INNER JOIN cd.facitiesの右側があります。それは把握するのに十分簡単です。ただし、左側は、Cd.membersをCd.Bookingsに結合することで返されたテーブルです。これを強調することが重要です。リレーショナルモデルはすべてテーブルに関するものです。任意の結合の出力は別のテーブルです。クエリの出力はテーブルです。単一の列リストはテーブルです。それを把握すると、モデルの基本的な美しさを把握しました。

最後のメモとして、ここに1つの新しいものを紹介します: ||オペレーターは、文字列を連結するために使用されます。

2012-09-14の日に予約のリストを作成するには、メンバー(またはゲスト)が30ドルを超える費用がかかりますか?ゲストはメンバーに異なるコストを持っていることを忘れないでください(リストされているコストは30分あたり「スロット」です)。ゲストユーザーは常にID 0です。出力には、施設の名前、メンバーの名前が単一の列としてフォーマットされたものとコストを含めます。下降コストで注文し、サブクリーリーを使用しないでください。

期待される結果:

| メンバー | 施設 | 料金 |

|---|---|---|

| ゲスト | マッサージルーム2 | 320 |

| ゲスト | マッサージルーム1 | 160 |

| ゲスト | マッサージルーム1 | 160 |

| ゲスト | マッサージルーム1 | 160 |

| ゲスト | テニスコート2 | 150 |

| ジェミマ・ファレル | マッサージルーム1 | 140 |

| ゲスト | テニスコート1 | 75 |

| ゲスト | テニスコート2 | 75 |

| ゲスト | テニスコート1 | 75 |

| マシュー・ゲンティン | マッサージルーム1 | 70 |

| フローレンス・バダー | マッサージルーム2 | 70 |

| ゲスト | スカッシュコート | 70.0 |

| ジェミマ・ファレル | マッサージルーム1 | 70 |

| 熟考するスティボン | マッサージルーム1 | 70 |

| バートン・トレーシー | マッサージルーム1 | 70 |

| ジャック・スミス | マッサージルーム1 | 70 |

| ゲスト | スカッシュコート | 35.0 |

| ゲスト | スカッシュコート | 35.0 |

答え:

select mems . firstname || ' ' || mems . surname as member,

facs . name as facility,

case

when mems . memid = 0 then

bks . slots * facs . guestcost

else

bks . slots * facs . membercost

end as cost

from

cd . members mems

inner join cd . bookings bks

on mems . memid = bks . memid

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

where

bks . starttime >= ' 2012-09-14 ' and

bks . starttime < ' 2012-09-15 ' and (

( mems . memid = 0 and bks . slots * facs . guestcost > 30 ) or

( mems . memid != 0 and bks . slots * facs . membercost > 30 )

)

order by cost desc ; これは少し複雑なものです!以前に使用したよりも複雑なロジックですが、発言することはあまりありません。 WHERE句は、2012-09-14の出力を2012-09-14に十分に費用のかかる列に制限し、ゲストと他の人を区別することを忘れないでください。次に、列選択のCASEステートメントを使用して、メンバーまたはゲストの正しいコストを出力します。

参加者を使用せずに(もしあれば)個人を含むすべてのメンバーのリストをどのように出力できますか?リストに重複がないこと、および各firstName + surnameペアリングが列としてフォーマットされ、注文されることを確認してください。

期待される結果:

| メンバー | 推奨 |

|---|---|

| アンナ・マッケンジー | ダレン・スミス |

| アン・ベイカー | 熟考するスティボン |

| バートン・トレーシー | |

| チャールズオーウェン | ダレン・スミス |

| ダレン・スミス | |

| デビッド・ファレル | |

| デビッド・ジョーンズ | ジャニス・ジョプレット |

| デビッド・ピンカー | ジェミマ・ファレル |

| ダグラス・ジョーンズ | デビッド・ジョーンズ |

| エリカ・クランペット | トレーシー・スミス |

| フローレンス・バダー | 熟考するスティボン |

| ゲスト | |

| ジェラルドバター | ダレン・スミス |

| ヘンリエッタ・ラニー | マシュー・ゲンティン |

| ヘンリー・ワージントン・スミス | トレーシー・スミス |

| Hyacinth Tupperware | |

| ジャック・スミス | ダレン・スミス |

| ジャニス・ジョプレット | ダレン・スミス |

| ジェミマ・ファレル | |

| ジョーン・コプリン | ティモシー・ベイカー |

| ジョン・ハント | ミリセントパビュー |

| マシュー・ゲンティン | ジェラルドバター |

| ミリセントパビュー | トレーシー・スミス |

| ナンシー・デア | ジャニス・ジョプレット |

| Ponder Stibbons | Burton Tracy |

| Ramnaresh Sarwin | Florence Bader |

| Tim Boothe | Tim Rownam |

| Tim Rownam | |

| Timothy Baker | Jemima Farrell |

| Tracy Smith |

答え:

select distinct mems . firstname || ' ' || mems . surname as member,

( select recs . firstname || ' ' || recs . surname as recommender

from cd . members recs

where recs . memid = mems . recommendedby

)

from

cd . members mems

order by member; This exercise marks the introduction of subqueries. Subqueries are, as the name implies, queries within a query. They're commonly used with aggregates, to answer questions like 'get me all the details of the member who has spent the most hours on Tennis Court 1'.

In this case, we're simply using the subquery to emulate an outer join. For every value of member, the subquery is run once to find the name of the individual who recommended them (if any). A subquery that uses information from the outer query in this way (and thus has to be run for each row in the result set) is known as a correlated subquery .

The Produce a list of costly bookings exercise contained some messy logic: we had to calculate the booking cost in both the WHERE clause and the CASE statement. Try to simplify this calculation using subqueries. For reference, the question was:

How can you produce a list of bookings on the day of 2012-09-14 which will cost the member (or guest) more than $30? Remember that guests have different costs to members (the listed costs are per half-hour 'slot'), and the guest user is always ID 0. Include in your output the name of the facility, the name of the member formatted as a single column, and the cost. Order by descending cost.

Expected results:

| メンバー | 施設 | 料金 |

|---|---|---|

| GUEST GUEST | Massage Room 2 | 320 |

| GUEST GUEST | Massage Room 1 | 160 |

| GUEST GUEST | Massage Room 1 | 160 |

| GUEST GUEST | Massage Room 1 | 160 |

| GUEST GUEST | Tennis Court 2 | 150 |

| Jemima Farrell | Massage Room 1 | 140 |

| GUEST GUEST | Tennis Court 1 | 75 |

| GUEST GUEST | Tennis Court 2 | 75 |

| GUEST GUEST | Tennis Court 1 | 75 |

| Matthew Genting | Massage Room 1 | 70 |

| Florence Bader | Massage Room 2 | 70 |

| GUEST GUEST | Squash Court | 70.0 |

| Jemima Farrell | Massage Room 1 | 70 |

| Ponder Stibbons | Massage Room 1 | 70 |

| Burton Tracy | Massage Room 1 | 70 |

| ジャック・スミス | Massage Room 1 | 70 |

| GUEST GUEST | Squash Court | 35.0 |

| GUEST GUEST | Squash Court | 35.0 |

答え:

select member, facility, cost from (

select

mems . firstname || ' ' || mems . surname as member,

facs . name as facility,

case

when mems . memid = 0 then

bks . slots * facs . guestcost

else

bks . slots * facs . membercost

end as cost

from

cd . members mems

inner join cd . bookings bks

on mems . memid = bks . memid

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

where

bks . starttime >= ' 2012-09-14 ' and

bks . starttime < ' 2012-09-15 '

) as bookings

where cost > 30

order by cost desc ; This answer provides a mild simplification to the previous iteration: in the no-subquery version, we had to calculate the member or guest's cost in both the WHERE clause and the CASE statement. In our new version, we produce an inline query that calculates the total booking cost for us, allowing the outer query to simply select the bookings it's looking for. For reference, you may also see subqueries in the FROM clause referred to as inline views .

Querying data is all well and good, but at some point you're probably going to want to put data into your database! This section deals with inserting, updating, and deleting information. Operations that alter your data like this are collectively known as Data Manipulation Language, or DML.

In previous sections, we returned to you the results of the query you've performed. Since modifications like the ones we're making in this section don't return any query results, we instead show you the updated content of the table you're supposed to be working on. You can compare this with the table shown in 'Expected Results' to see how you've done.

If you struggle with these questions, I strongly recommend Learning SQL, by Alan Beaulieu.

The club is adding a new facility - a spa. We need to add it into the facilities table. Use the following values:

Expected results:

| facid | 名前 | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | 卓球 | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Pool Table | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

| 9 | スパ | 20 | 30 | 100000 | 800 |

答え:

insert into cd . facilities

(facid, name, membercost, guestcost, initialoutlay, monthlymaintenance)

values ( 9 , ' Spa ' , 20 , 30 , 100000 , 800 ); INSERT INTO ... VALUES is the simplest way to insert data into a table. There's not a whole lot to discuss here: VALUES is used to construct a row of data, which the INSERT statement inserts into the table. It's a simple as that.

You can see that there's two sections in parentheses. The first is part of the INSERT statement, and specifies the columns that we're providing data for. The second is part of VALUES , and specifies the actual data we want to insert into each column.

If we're inserting data into every column of the table, as in this example, explicitly specifying the column names is optional. As long as you fill in data for all columns of the table, in the order they were defined when you created the table, you can do something like the following:

insert into cd . facilities values ( 9 , ' Spa ' , 20 , 30 , 100000 , 800 );Generally speaking, for SQL that's going to be reused I tend to prefer being explicit and specifying the column names.

In the previous exercise, you learned how to add a facility. Now you're going to add multiple facilities in one command. Use the following values:

Expected results:

| facid | 名前 | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | 卓球 | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Pool Table | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

| 9 | スパ | 20 | 30 | 100000 | 800 |

| 10 | Squash Court 2 | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

答え:

insert into cd . facilities

(facid, name, membercost, guestcost, initialoutlay, monthlymaintenance)

values

( 9 , ' Spa ' , 20 , 30 , 100000 , 800 ),

( 10 , ' Squash Court 2 ' , 3 . 5 , 17 . 5 , 5000 , 80 ); VALUES can be used to generate more than one row to insert into a table, as seen in this example. Hopefully it's clear what's going on here: the output of VALUES is a table, and that table is copied into cd.facilities, the table specified in the INSERT command.

While you'll most commonly see VALUES when inserting data, Postgres allows you to use VALUES wherever you might use a SELECT . This makes sense: the output of both commands is a table, it's just that VALUES is a bit more ergonomic when working with constant data.

Similarly, it's possible to use SELECT wherever you see a VALUES . This means that you can INSERT the results of a SELECT .例えば:

insert into cd . facilities

(facid, name, membercost, guestcost, initialoutlay, monthlymaintenance)

SELECT 9 , ' Spa ' , 20 , 30 , 100000 , 800

UNION ALL

SELECT 10 , ' Squash Court 2 ' , 3 . 5 , 17 . 5 , 5000 , 80 ; In later exercises you'll see us using INSERT ... SELECT to generate data to insert based on the information already in the database.

Let's try adding the spa to the facilities table again. This time, though, we want to automatically generate the value for the next facid, rather than specifying it as a constant. Use the following values for everything else:

Expected results:

| facid | 名前 | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | 卓球 | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Pool Table | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

| 9 | スパ | 20 | 30 | 100000 | 800 |

答え:

insert into cd . facilities

(facid, name, membercost, guestcost, initialoutlay, monthlymaintenance)

select ( select max (facid) from cd . facilities ) + 1 , ' Spa ' , 20 , 30 , 100000 , 800 ; In the previous exercises we used VALUES to insert constant data into the facilities table. Here, though, we have a new requirement: a dynamically generated ID. This gives us a real quality of life improvement, as we don't have to manually work out what the current largest ID is: the SQL command does it for us.

Since the VALUES clause is only used to supply constant data, we need to replace it with a query instead. The SELECT statement is fairly simple: there's an inner subquery that works out the next facid based on the largest current id, and the rest is just constant data. The output of the statement is a row that we insert into the facilities table.

While this works fine in our simple example, it's not how you would generally implement an incrementing ID in the real world. Postgres provides SERIAL types that are auto-filled with the next ID when you insert a row. As well as saving us effort, these types are also safer: unlike the answer given in this exercise, there's no need to worry about concurrent operations generating the same ID.

We made a mistake when entering the data for the second tennis court. The initial outlay was 10000 rather than 8000: you need to alter the data to fix the error.

Expected results:

| facid | 名前 | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | 卓球 | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Pool Table | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

答え:

update cd . facilities

set initialoutlay = 10000

where facid = 1 ; The UPDATE statement is used to alter existing data. If you're familiar with SELECT queries, it's pretty easy to read: the WHERE clause works in exactly the same fashion, allowing us to filter the set of rows we want to work with. These rows are then modified according to the specifications of the SET clause: in this case, setting the initial outlay.

The WHERE clause is extremely important. It's easy to get it wrong or even omit it, with disastrous results. Consider the following command:

update cd . facilities

set initialoutlay = 10000 ; There's no WHERE clause to filter for the rows we're interested in. The result of this is that the update runs on every row in the table! This is rarely what we want to happen.

We want to increase the price of the tennis courts for both members and guests. Update the costs to be 6 for members, and 30 for guests.

| facid | 名前 | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 6 | 30 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 6 | 30 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | 卓球 | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Pool Table | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

答え:

update cd . facilities

set

membercost = 6 ,

guestcost = 30

where facid in ( 0 , 1 ); The SET clause accepts a comma separated list of values that you want to update.

We want to alter the price of the second tennis court so that it costs 10% more than the first one. Try to do this without using constant values for the prices, so that we can reuse the statement if we want to.

Expected results:

| facid | 名前 | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 5.5 | 27.5 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | 卓球 | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Pool Table | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

答え:

update cd . facilities facs

set

membercost = ( select membercost * 1 . 1 from cd . facilities where facid = 0 ),

guestcost = ( select guestcost * 1 . 1 from cd . facilities where facid = 0 )

where facs . facid = 1 ; Updating columns based on calculated data is not too intrinsically difficult: we can do so pretty easily using subqueries. You can see this approach in our selected answer.

As the number of columns we want to update increases, standard SQL can start to get pretty awkward: you don't want to be specifying a separate subquery for each of 15 different column updates. Postgres provides a nonstandard extension to SQL called UPDATE...FROM that addresses this: it allows you to supply a FROM clause to generate values for use in the SET clause. Example below:

update cd . facilities facs

set

membercost = facs2 . membercost * 1 . 1 ,

guestcost = facs2 . guestcost * 1 . 1

from ( select * from cd . facilities where facid = 0 ) facs2

where facs . facid = 1 ;As part of a clearout of our database, we want to delete all bookings from the cd.bookings table. How can we accomplish this?

Expected results:

| bookid | facid | memid | starttime | slots |

|---|---|---|---|---|

答え:

delete from cd . bookings ; The DELETE statement does what it says on the tin: deletes rows from the table. Here, we show the command in its simplest form, with no qualifiers. In this case, it deletes everything from the table. Obviously, you should be careful with your deletes and make sure they're always limited - we'll see how to do that in the next exercise.

An alternative to unqualified DELETE s is the following:

truncate cd . bookings ; TRUNCATE also deletes everything in the table, but does so using a quicker underlying mechanism. It's not perfectly safe in all circumstances, though, so use judiciously. When in doubt, use DELETE .

We want to remove member 37, who has never made a booking, from our database. How can we achieve that?

Expected results:

| memid | 姓 | ファーストネーム | 住所 | 郵便番号 | 電話 | recommendedby | joindate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ゲスト | ゲスト | ゲスト | 0 | (000) 000-0000 | 2012-07-01 00:00:00 | |

| 1 | Smith | ダレン | 8 Bloomsbury Close, Boston | 4321 | 555-555-5555 | 2012-07-02 12:02:05 | |

| 2 | Smith | Tracy | 8 Bloomsbury Close, New York | 4321 | 555-555-5555 | 2012-07-02 12:08:23 | |

| 3 | Rownam | Tim | 23 Highway Way, Boston | 23423 | (844) 693-0723 | 2012-07-03 09:32:15 | |

| 4 | Joplette | ジャニス | 20 Crossing Road, New York | 234 | (833) 942-4710 | 1 | 2012-07-03 10:25:05 |

| 5 | Butters | ジェラルド | 1065 Huntingdon Avenue, Boston | 56754 | (844) 078-4130 | 1 | 2012-07-09 10:44:09 |

| 6 | Tracy | バートン | 3 Tunisia Drive, Boston | 45678 | (822) 354-9973 | 2012-07-15 08:52:55 | |

| 7 | Dare | ナンシー | 6 Hunting Lodge Way, Boston | 10383 | (833) 776-4001 | 4 | 2012-07-25 08:59:12 |

| 8 | Boothe | Tim | 3 Bloomsbury Close, Reading, 00234 | 234 | (811) 433-2547 | 3 | 2012-07-25 16:02:35 |

| 9 | Stibbons | Ponder | 5 Dragons Way, Winchester | 87630 | (833) 160-3900 | 6 | 2012-07-25 17:09:05 |

| 10 | オーウェン | チャールズ | 52 Cheshire Grove, Winchester, 28563 | 28563 | (855) 542-5251 | 1 | 2012-08-03 19:42:37 |

| 11 | ジョーンズ | デビッド | 976 Gnats Close, Reading | 33862 | (844) 536-8036 | 4 | 2012-08-06 16:32:55 |

| 12 | ベイカー | アン | 55 Powdery Street, Boston | 80743 | 844-076-5141 | 9 | 2012-08-10 14:23:22 |

| 13 | Farrell | Jemima | 103 Firth Avenue, North Reading | 57392 | (855) 016-0163 | 2012-08-10 14:28:01 | |

| 14 | Smith | ジャック | 252 Binkington Way, Boston | 69302 | (822) 163-3254 | 1 | 2012-08-10 16:22:05 |

| 15 | Bader | フィレンツェ | 264 Ursula Drive, Westford | 84923 | (833) 499-3527 | 9 | 2012-08-10 17:52:03 |

| 16 | ベイカー | ティモシー | 329 James Street, Reading | 58393 | 833-941-0824 | 13 | 2012-08-15 10:34:25 |

| 17 | Pinker | デビッド | 5 Impreza Road, Boston | 65332 | 811 409-6734 | 13 | 2012-08-16 11:32:47 |

| 20 | Genting | マシュー | 4 Nunnington Place, Wingfield, Boston | 52365 | (811) 972-1377 | 5 | 2012-08-19 14:55:55 |

| 21 | Mackenzie | アンナ | 64 Perkington Lane, Reading | 64577 | (822) 661-2898 | 1 | 2012-08-26 09:32:05 |

| 22 | Coplin | Joan | 85 Bard Street, Bloomington, Boston | 43533 | (822) 499-2232 | 16 | 2012-08-29 08:32:41 |

| 24 | Sarwin | Ramnaresh | 12 Bullington Lane, Boston | 65464 | (822) 413-1470 | 15 | 2012-09-01 08:44:42 |

| 26 | ジョーンズ | ダグラス | 976 Gnats Close, Reading | 11986 | 844 536-8036 | 11 | 2012-09-02 18:43:05 |

| 27 | Rumney | Henrietta | 3 Burkington Plaza, Boston | 78533 | (822) 989-8876 | 20 | 2012-09-05 08:42:35 |

| 28 | Farrell | デビッド | 437 Granite Farm Road, Westford | 43532 | (855) 755-9876 | 2012-09-15 08:22:05 | |

| 29 | Worthington-Smyth | ヘンリー | 55 Jagbi Way, North Reading | 97676 | (855) 894-3758 | 2 | 2012-09-17 12:27:15 |

| 30 | Purview | Millicent | 641 Drudgery Close, Burnington, Boston | 34232 | (855) 941-9786 | 2 | 2012-09-18 19:04:01 |

| 33 | Tupperware | Hyacinth | 33 Cheerful Plaza, Drake Road, Westford | 68666 | (822) 665-5327 | 2012-09-18 19:32:05 | |

| 35 | ハント | ジョン | 5 Bullington Lane, Boston | 54333 | (899) 720-6978 | 30 | 2012-09-19 11:32:45 |

| 36 | Crumpet | エリカ | Crimson Road, North Reading | 75655 | (811) 732-4816 | 2 | 2012-09-22 08:36:38 |

答え:

delete from cd . members where memid = 37 ; This exercise is a small increment on our previous one. Instead of deleting all bookings, this time we want to be a bit more targeted, and delete a single member that has never made a booking. To do this, we simply have to add a WHERE clause to our command, specifying the member we want to delete. You can see the parallels with SELECT and UPDATE statements here.

There's one interesting wrinkle here. Try this command out, but substituting in member id 0 instead. This member has made many bookings, and you'll find that the delete fails with an error about a foreign key constraint violation. This is an important concept in relational databases, so let's explore a little further.

Foreign keys are a mechanism for defining relationships between columns of different tables. In our case we use them to specify that the memid column of the bookings table is related to the memid column of the members table. The relationship (or 'constraint') specifies that for a given booking, the member specified in the booking must exist in the members table. It's useful to have this guarantee enforced by the database: it means that code using the database can rely on the presence of the member. It's hard (even impossible) to enforce this at higher levels: concurrent operations can interfere and leave your database in a broken state.

PostgreSQL supports various different kinds of constraints that allow you to enforce structure upon your data. For more information on constraints, check out the PostgreSQL documentation on foreign keys

In our previous exercises, we deleted a specific member who had never made a booking. How can we make that more general, to delete all members who have never made a booking?

Expected results:

| memid | 姓 | ファーストネーム | 住所 | 郵便番号 | 電話 | recommendedby | joindate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ゲスト | ゲスト | ゲスト | 0 | (000) 000-0000 | 2012-07-01 00:00:00 | |

| 1 | Smith | ダレン | 8 Bloomsbury Close, Boston | 4321 | 555-555-5555 | 2012-07-02 12:02:05 | |

| 2 | Smith | Tracy | 8 Bloomsbury Close, New York | 4321 | 555-555-5555 | 2012-07-02 12:08:23 | |

| 3 | Rownam | Tim | 23 Highway Way, Boston | 23423 | (844) 693-0723 | 2012-07-03 09:32:15 | |

| 4 | Joplette | ジャニス | 20 Crossing Road, New York | 234 | (833) 942-4710 | 1 | 2012-07-03 10:25:05 |

| 5 | Butters | ジェラルド | 1065 Huntingdon Avenue, Boston | 56754 | (844) 078-4130 | 1 | 2012-07-09 10:44:09 |

| 6 | Tracy | バートン | 3 Tunisia Drive, Boston | 45678 | (822) 354-9973 | 2012-07-15 08:52:55 | |

| 7 | Dare | ナンシー | 6 Hunting Lodge Way, Boston | 10383 | (833) 776-4001 | 4 | 2012-07-25 08:59:12 |

| 8 | Boothe | Tim | 3 Bloomsbury Close, Reading, 00234 | 234 | (811) 433-2547 | 3 | 2012-07-25 16:02:35 |

| 9 | Stibbons | Ponder | 5 Dragons Way, Winchester | 87630 | (833) 160-3900 | 6 | 2012-07-25 17:09:05 |

| 10 | オーウェン | チャールズ | 52 Cheshire Grove, Winchester, 28563 | 28563 | (855) 542-5251 | 1 | 2012-08-03 19:42:37 |

| 11 | ジョーンズ | デビッド | 976 Gnats Close, Reading | 33862 | (844) 536-8036 | 4 | 2012-08-06 16:32:55 |

| 12 | ベイカー | アン | 55 Powdery Street, Boston | 80743 | 844-076-5141 | 9 | 2012-08-10 14:23:22 |

| 13 | Farrell | Jemima | 103 Firth Avenue, North Reading | 57392 | (855) 016-0163 | 2012-08-10 14:28:01 | |

| 14 | Smith | ジャック | 252 Binkington Way, Boston | 69302 | (822) 163-3254 | 1 | 2012-08-10 16:22:05 |

| 15 | Bader | フィレンツェ | 264 Ursula Drive, Westford | 84923 | (833) 499-3527 | 9 | 2012-08-10 17:52:03 |

| 16 | ベイカー | ティモシー | 329 James Street, Reading | 58393 | 833-941-0824 | 13 | 2012-08-15 10:34:25 |

| 17 | Pinker | デビッド | 5 Impreza Road, Boston | 65332 | 811 409-6734 | 13 | 2012-08-16 11:32:47 |

| 20 | Genting | マシュー | 4 Nunnington Place, Wingfield, Boston | 52365 | (811) 972-1377 | 5 | 2012-08-19 14:55:55 |

| 21 | Mackenzie | アンナ | 64 Perkington Lane, Reading | 64577 | (822) 661-2898 | 1 | 2012-08-26 09:32:05 |

| 22 | Coplin | Joan | 85 Bard Street, Bloomington, Boston | 43533 | (822) 499-2232 | 16 | 2012-08-29 08:32:41 |

| 24 | Sarwin | Ramnaresh | 12 Bullington Lane, Boston | 65464 | (822) 413-1470 | 15 | 2012-09-01 08:44:42 |

| 26 | ジョーンズ | ダグラス | 976 Gnats Close, Reading | 11986 | 844 536-8036 | 11 | 2012-09-02 18:43:05 |

| 27 | Rumney | Henrietta | 3 Burkington Plaza, Boston | 78533 | (822) 989-8876 | 20 | 2012-09-05 08:42:35 |

| 28 | Farrell | デビッド | 437 Granite Farm Road, Westford | 43532 | (855) 755-9876 | 2012-09-15 08:22:05 | |

| 29 | Worthington-Smyth | ヘンリー | 55 Jagbi Way, North Reading | 97676 | (855) 894-3758 | 2 | 2012-09-17 12:27:15 |

| 30 | Purview | Millicent | 641 Drudgery Close, Burnington, Boston | 34232 | (855) 941-9786 | 2 | 2012-09-18 19:04:01 |

| 33 | Tupperware | Hyacinth | 33 Cheerful Plaza, Drake Road, Westford | 68666 | (822) 665-5327 | 2012-09-18 19:32:05 | |

| 35 | ハント | ジョン | 5 Bullington Lane, Boston | 54333 | (899) 720-6978 | 30 | 2012-09-19 11:32:45 |

| 36 | Crumpet | エリカ | Crimson Road, North Reading | 75655 | (811) 732-4816 | 2 | 2012-09-22 08:36:38 |

答え:

delete from cd . members where memid not in ( select memid from cd . bookings ); We can use subqueries to determine whether a row should be deleted or not. There's a couple of standard ways to do this. In our featured answer, the subquery produces a list of all the different member ids in the cd.bookings table. If a row in the table isn't in the list generated by the subquery, it gets deleted.

An alternative is to use a correlated subquery . Where our previous example runs a large subquery once, the correlated approach instead specifies a smaller subqueryto run against every row.

delete from cd . members mems where not exists ( select 1 from cd . bookings where memid = mems . memid );The two different forms can have different performance characteristics. Under the hood, your database engine is free to transform your query to execute it in a correlated or uncorrelated fashion, though, so things can be a little hard to predict.

Aggregation is one of those capabilities that really make you appreciate the power of relational database systems. It allows you to move beyond merely persisting your data, into the realm of asking truly interesting questions that can be used to inform decision making. This category covers aggregation at length, making use of standard grouping as well as more recent window functions.

If you struggle with these questions, I strongly recommend Learning SQL, by Alan Beaulieu and SQL Cookbook by Anthony Molinaro. In fact, get the latter anyway - it'll take you beyond anything you find on this site, and on multiple different database systems to boot.

For our first foray into aggregates, we're going to stick to something simple. We want to know how many facilities exist - simply produce a total count.

Expected results:

| カウント |

|---|

| 9 |

答え:

select count ( * ) from cd . facilities ; Aggregation starts out pretty simply! The SQL above selects everything from our facilities table, and then counts the number of rows in the result set. The count function has a variety of uses:

COUNT(*) simply returns the number of rowsCOUNT(address) counts the number of non-null addresses in the result set.COUNT(DISTINCT address) counts the number of different addresses in the facilities table. The basic idea of an aggregate function is that it takes in a column of data, performs some function upon it, and outputs a scalar (single) value. There are a bunch more aggregation functions, including MAX , MIN , SUM , and AVG . These all do pretty much what you'd expect from their names :-).

One aspect of aggregate functions that people often find confusing is in queries like the below:

select facid, count ( * ) from cd . facilitiesTry it out, and you'll find that it doesn't work. This is because count(*) wants to collapse the facilities table into a single value - unfortunately, it can't do that, because there's a lot of different facids in cd.facilities - Postgres doesn't know which facid to pair the count with.

Instead, if you wanted a query that returns all the facids along with a count on each row, you can break the aggregation out into a subquery as below:

select facid,

( select count ( * ) from cd . facilities )

from cd . facilitiesWhen we have a subquery that returns a scalar value like this, Postgres knows to simply repeat the value for every row in cd.facilities.

Produce a count of the number of facilities that have a cost to guests of 10 or more.

| カウント |

|---|

| 6 |

答え:

select count ( * ) from cd . facilities where guestcost >= 10 ; This one is only a simple modification to the previous question: we need to weed out the inexpensive facilities. This is easy to do using a WHERE clause. Our aggregation can now only see the expensive facilities.

Produce a count of the number of recommendations each member has made. Order by member ID.

Expected results:

| recommendedby | カウント |

|---|---|

| 1 | 5 |

| 2 | 3 |

| 3 | 1 |

| 4 | 2 |

| 5 | 1 |

| 6 | 1 |

| 9 | 2 |

| 11 | 1 |

| 13 | 2 |

| 15 | 1 |

| 16 | 1 |

| 20 | 1 |

| 30 | 1 |

答え:

select recommendedby, count ( * )

from cd . members

where recommendedby is not null

group by recommendedby

order by recommendedby; Previously, we've seen that aggregation functions are applied to a column of values, and convert them into an aggregated scalar value. This is useful, but we often find that we don't want just a single aggregated result: for example, instead of knowing the total amount of money the club has made this month, I might want to know how much money each different facility has made, or which times of day were most lucrative.

In order to support this kind of behaviour, SQL has the GROUP BY construct. What this does is batch the data together into groups, and run the aggregation function separately for each group. When you specify a GROUP BY , the database produces an aggregated value for each distinct value in the supplied columns. In this case, we're saying 'for each distinct value of recommendedby, get me the number of times that value appears'.

Produce a list of the total number of slots booked per facility. For now, just produce an output table consisting of facility id and slots, sorted by facility id.

Expected results:

| facid | Total Slots |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1320 |

| 1 | 1278 |

| 2 | 1209 |

| 3 | 830 |

| 4 | 1404 |

| 5 | 228 |

| 6 | 1104 |

| 7 | 908 |

| 8 | 911 |

答え:

select facid, sum (slots) as " Total Slots "

from cd . bookings

group by facid

order by facid; Other than the fact that we've introduced the SUM aggregate function, there's not a great deal to say about this exercise. For each distinct facility id, the SUM function adds together everything in the slots column.

Produce a list of the total number of slots booked per facility in the month of September 2012. Produce an output table consisting of facility id and slots, sorted by the number of slots.

Expected results:

| facid | Total Slots |

|---|---|

| 5 | 122 |

| 3 | 422 |

| 7 | 426 |

| 8 | 471 |

| 6 | 540 |

| 2 | 570 |

| 1 | 588 |

| 0 | 591 |

| 4 | 648 |

答え:

select facid, sum (slots) as " Total Slots "

from cd . bookings

where

starttime >= ' 2012-09-01 '

and starttime < ' 2012-10-01 '

group by facid

order by sum (slots); This is only a minor alteration of our previous example. Remember that aggregation happens after the WHERE clause is evaluated: we thus use the WHERE to restrict the data we aggregate over, and our aggregation only sees data from a single month.

Produce a list of the total number of slots booked per facility per month in the year of 2012. Produce an output table consisting of facility id and slots, sorted by the id and month.

Expected results:

| facid | 月 | Total Slots |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 7 | 270 |

| 0 | 8 | 459 |

| 0 | 9 | 591 |

| 1 | 7 | 207 |

| 1 | 8 | 483 |

| 1 | 9 | 588 |

| 2 | 7 | 180 |

| 2 | 8 | 459 |

| 2 | 9 | 570 |

| 3 | 7 | 104 |

| 3 | 8 | 304 |

| 3 | 9 | 422 |

| 4 | 7 | 264 |

| 4 | 8 | 492 |

| 4 | 9 | 648 |

| 5 | 7 | 24 |

| 5 | 8 | 82 |

| 5 | 9 | 122 |

| 6 | 7 | 164 |

| 6 | 8 | 400 |

| 6 | 9 | 540 |

| 7 | 7 | 156 |

| 7 | 8 | 326 |

| 7 | 9 | 426 |

| 8 | 7 | 117 |

| 8 | 8 | 322 |

| 8 | 9 | 471 |

答え:

select facid, extract(month from starttime) as month, sum (slots) as " Total Slots "

from cd . bookings

where

starttime >= ' 2012-01-01 '

and starttime < ' 2013-01-01 '

group by facid, month

order by facid, month; The main piece of new functionality in this question is the EXTRACT function. EXTRACT allows you to get individual components of a timestamp, like day, month, year, etc. We group by the output of this function to provide per-month values. An alternative, if we needed to distinguish between the same month in different years, is to make use of the DATE_TRUNC function, which truncates a date to a given granularity.

It's also worth noting that this is the first time we've truly made use of the ability to group by more than one column.

Find the total number of members who have made at least one booking.

Expected results:

| カウント |

|---|

| 30 |

答え:

select count (distinct memid) from cd . bookings Your first instinct may be to go for a subquery here. Something like the below:

select count ( * ) from

( select distinct memid from cd . bookings ) as mems This does work perfectly well, but we can simplify a touch with the help of a little extra knowledge in the form of COUNT DISTINCT . This does what you might expect, counting the distinct values in the passed column.

Produce a list of facilities with more than 1000 slots booked. Produce an output table consisting of facility id and hours, sorted by facility id.

Expected results:

| facid | Total Slots |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1320 |

| 1 | 1278 |

| 2 | 1209 |

| 4 | 1404 |

| 6 | 1104 |

答え:

select facid, sum (slots) as " Total Slots "

from cd . bookings

group by facid

having sum (slots) > 1000

order by facid It turns out that there's actually an SQL keyword designed to help with the filtering of output from aggregate functions. This keyword is HAVING .

The behaviour of HAVING is easily confused with that of WHERE . The best way to think about it is that in the context of a query with an aggregate function, WHERE is used to filter what data gets input into the aggregate function, while HAVING is used to filter the data once it is output from the function. Try experimenting to explore this difference!

Produce a list of facilities along with their total revenue. The output table should consist of facility name and revenue, sorted by revenue. Remember that there's a different cost for guests and members!

Expected results:

| 名前 | 収益 |

|---|---|

| 卓球 | 180 |

| Snooker Table | 240 |

| Pool Table | 270 |

| Badminton Court | 1906.5 |

| Squash Court | 13468.0 |

| Tennis Court 1 | 13860 |

| Tennis Court 2 | 14310 |

| Massage Room 2 | 15810 |

| Massage Room 1 | 72540 |

答え:

select facs . name , sum (slots * case

when memid = 0 then facs . guestcost

else facs . membercost

end) as revenue

from cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

group by facs . name

order by revenue; The only real complexity in this query is that guests (member ID 0) have a different cost to everyone else. We use a case statement to produce the cost for each session, and then sum each of those sessions, grouped by facility.

Produce a list of facilities with a total revenue less than 1000. Produce an output table consisting of facility name and revenue, sorted by revenue. Remember that there's a different cost for guests and members!

Expected results:

| 名前 | 収益 |

|---|---|

| 卓球 | 180 |

| Snooker Table | 240 |

| Pool Table | 270 |

答え:

select name, revenue from (

select facs . name , sum (case

when memid = 0 then slots * facs . guestcost

else slots * membercost

end) as revenue

from cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

group by facs . name

) as agg where revenue < 1000

order by revenue; You may well have tried to use the HAVING keyword we introduced in an earlier exercise, producing something like below:

select facs . name , sum (case

when memid = 0 then slots * facs . guestcost

else slots * membercost

end) as revenue

from cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

group by facs . name

having revenue < 1000

order by revenue; Unfortunately, this doesn't work! You'll get an error along the lines of ERROR: column "revenue" does not exist . Postgres, unlike some other RDBMSs like SQL Server and MySQL, doesn't support putting column names in the HAVING clause. This means that for this query to work, you'd have to produce something like below:

select facs . name , sum (case

when memid = 0 then slots * facs . guestcost

else slots * membercost

end) as revenue

from cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

group by facs . name

having sum (case

when memid = 0 then slots * facs . guestcost

else slots * membercost

end) < 1000

order by revenue; Having to repeat significant calculation code like this is messy, so our anointed solution instead just wraps the main query body as a subquery, and selects from it using a WHERE clause. In general, I recommend using HAVING for simple queries, as it increases clarity. Otherwise, this subquery approach is often easier to use.

Output the facility id that has the highest number of slots booked. For bonus points, try a version without a LIMIT clause. This version will probably look messy!

Expected results:

| facid | Total Slots |

|---|---|

| 4 | 1404 |

答え:

select facid, sum (slots) as " Total Slots "

from cd . bookings

group by facid

order by sum (slots) desc

LIMIT 1 ; Let's start off with what's arguably the simplest way to do this: produce a list of facility IDs and the total number of slots used, order by the total number of slots used, and pick only the top result.

It's worth realising, though, that this method has a significant weakness. In the event of a tie, we will still only get one result! To get all the relevant results, we might try using the MAX aggregate function, something like below:

select facid, max (totalslots) from (

select facid, sum (slots) as totalslots

from cd . bookings

group by facid

) as sub group by facid The intent of this query is to get the highest totalslots value and its associated facid(s). Unfortunately, this just won't work! In the event of multiple facids having the same number of slots booked, it would be ambiguous which facid should be paired up with the single (or scalar ) value coming out of the MAX function. This means that Postgres will tell you that facid ought to be in a GROUP BY section, which won't produce the results we're looking for.

Let's take a first stab at a working query:

select facid, sum (slots) as totalslots

from cd . bookings

group by facid

having sum (slots) = ( select max ( sum2 . totalslots ) from

( select sum (slots) as totalslots

from cd . bookings

group by facid

) as sum2);The query produces a list of facility IDs and number of slots used, and then uses a HAVING clause that works out the maximum totalslots value. We're essentially saying: 'produce a list of facids and their number of slots booked, and filter out all the ones that doen't have a number of slots booked equal to the maximum.'

Useful as HAVING is, however, our query is pretty ugly. To improve on that, let's introduce another new concept: Common Table Expressions (CTEs). CTEs can be thought of as allowing you to define a database view inline in your query. It's really helpful in situations like this, where you're having to repeat yourself a lot.

CTEs are declared in the form WITH CTEName as (SQL-Expression) . You can see our query redefined to use a CTE below:

with sum as ( select facid, sum (slots) as totalslots

from cd . bookings

group by facid

)

select facid, totalslots

from sum

where totalslots = ( select max (totalslots) from sum);You can see that we've factored out our repeated selections from cd.bookings into a single CTE, and made the query a lot simpler to read in the process!

BUT WAIT.もっとあります。 It's also possible to complete this problem using Window Functions. We'll leave these until later, but even better solutions to problems like these are available.

That's a lot of information for a single exercise. Don't worry too much if you don't get it all right now - we'll reuse these concepts in later exercises.

Produce a list of the total number of slots booked per facility per month in the year of 2012. In this version, include output rows containing totals for all months per facility, and a total for all months for all facilities. The output table should consist of facility id, month and slots, sorted by the id and month. When calculating the aggregated values for all months and all facids, return null values in the month and facid columns.

Expected results:

| facid | 月 | slots |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 7 | 270 |

| 0 | 8 | 459 |

| 0 | 9 | 591 |

| 0 | 1320 | |

| 1 | 7 | 207 |

| 1 | 8 | 483 |

| 1 | 9 | 588 |

| 1 | 1278 | |

| 2 | 7 | 180 |

| 2 | 8 | 459 |

| 2 | 9 | 570 |

| 2 | 1209 | |

| 3 | 7 | 104 |

| 3 | 8 | 304 |

| 3 | 9 | 422 |

| 3 | 830 | |

| 4 | 7 | 264 |

| 4 | 8 | 492 |

| 4 | 9 | 648 |

| 4 | 1404 | |

| 5 | 7 | 24 |

| 5 | 8 | 82 |

| 5 | 9 | 122 |

| 5 | 228 | |

| 6 | 7 | 164 |

| 6 | 8 | 400 |

| 6 | 9 | 540 |

| 6 | 1104 | |

| 7 | 7 | 156 |

| 7 | 8 | 326 |

| 7 | 9 | 426 |

| 7 | 908 | |

| 8 | 7 | 117 |

| 8 | 8 | 322 |

| 8 | 9 | 471 |

| 8 | 910 | |

| 9191 |

答え:

select facid, extract(month from starttime) as month, sum (slots) as slots

from cd . bookings

where

starttime >= ' 2012-01-01 '

and starttime < ' 2013-01-01 '

group by rollup(facid, month)

order by facid, month; When we are doing data analysis, we sometimes want to perform multiple levels of aggregation to allow ourselves to 'zoom' in and out to different depths. In this case, we might be looking at each facility's overall usage, but then want to dive in to see how they've performed on a per-month basis. Using the SQL we know so far, it's quite cumbersome to produce a single query that does what we want - we effectively have to resort to concatenating multiple queries using UNION ALL :

select facid, extract(month from starttime) as month, sum (slots) as slots

from cd . bookings

where

starttime >= ' 2012-01-01 '

and starttime < ' 2013-01-01 '

group by facid, month

union all

select facid, null , sum (slots) as slots

from cd . bookings

where

starttime >= ' 2012-01-01 '

and starttime < ' 2013-01-01 '

group by facid

union all

select null , null , sum (slots) as slots

from cd . bookings

where

starttime >= ' 2012-01-01 '

and starttime < ' 2013-01-01 '

order by facid, month;As you can see, each subquery performs a different level of aggregation, and we just combine the results. We can clean this up a lot by factoring out commonalities using a CTE:

with bookings as (

select facid, extract(month from starttime) as month, slots

from cd . bookings

where

starttime >= ' 2012-01-01 '

and starttime < ' 2013-01-01 '

)

select facid, month, sum (slots) from bookings group by facid, month

union all

select facid, null , sum (slots) from bookings group by facid

union all

select null , null , sum (slots) from bookings

order by facid, month; This version is not excessively hard on the eyes, but it becomes cumbersome as the number of aggregation columns increases. Fortunately, PostgreSQL 9.5 introduced support for the ROLLUP operator, which we've used to simplify our accepted answer.

ROLLUP produces a hierarchy of aggregations in the order passed into it: for example, ROLLUP(facid, month) outputs aggregations on (facid, month), (facid), and (). If we wanted an aggregation of all facilities for a month (instead of all months for a facility) we'd have to reverse the order, using ROLLUP(month, facid) . Alternatively, if we instead want all possible permutations of the columns we pass in, we can use CUBE rather than ROLLUP . This will produce (facid, month), (month), (facid), and ().

ROLLUP and CUBE are special cases of GROUPING SETS . GROUPING SETS allow you to specify the exact aggregation permutations you want: you could, for example, ask for just (facid, month) and (facid), skipping the top-level aggregation.

Produce a list of the total number of hours booked per facility, remembering that a slot lasts half an hour. The output table should consist of the facility id, name, and hours booked, sorted by facility id. Try formatting the hours to two decimal places.

Expected results:

| facid | 名前 | Total Hours |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 660.00 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 639.00 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 604.50 |

| 3 | 卓球 | 415.00 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 702.00 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 114.00 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 552.00 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 454.00 |

| 8 | Pool Table | 455.50 |

答え:

select facs . facid , facs . name ,

trim (to_char( sum ( bks . slots ) / 2 . 0 , ' 9999999999999999D99 ' )) as " Total Hours "

from cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . facilities facs

on facs . facid = bks . facid

group by facs . facid , facs . name

order by facs . facid ; There's a few little pieces of interest in this question. Firstly, you can see that our aggregation works just fine when we join to another table on a 1:1 basis. Also note that we group by both facs.facid and facs.name . This is might seem odd: after all, since facid is the primary key of the facilities table, each facid has exactly one name, and grouping by both fields is the same as grouping by facid alone. In fact, you'll find that if you remove facs.name from the GROUP BY clause, the query works just fine: Postgres works out that this 1:1 mapping exists, and doesn't insist that we group by both columns.

Unfortunately, depending on which database system we use, validation might not be so smart, and may not realise that the mapping is strictly 1:1. That being the case, if there were multiple names for each facid and we hadn't grouped by name , the DBMS would have to choose between multiple (equally valid) choices for the name . Since this is invalid, the database system will insist that we group by both fields. In general, I recommend grouping by all columns you don't have an aggregate function on: this will ensure better cross-platform compatibility.

Next up is the division. Those of you familiar with MySQL may be aware that integer divisions are automatically cast to floats. Postgres is a little more traditional in this respect, and expects you to tell it if you want a floating point division. You can do that easily in this case by dividing by 2.0 rather than 2.

Finally, let's take a look at formatting. The TO_CHAR function converts values to character strings. It takes a formatting string, which we specify as (up to) lots of numbers before the decimal place, decimal place, and two numbers after the decimal place. The output of this function can be prepended with a space, which is why we include the outer TRIM function.

Produce a list of each member name, id, and their first booking after September 1st 2012. Order by member ID.

Expected results:

| 姓 | ファーストネーム | memid | starttime |

|---|---|---|---|

| ゲスト | ゲスト | 0 | 2012-09-01 08:00:00 |

| Smith | ダレン | 1 | 2012-09-01 09:00:00 |

| Smith | Tracy | 2 | 2012-09-01 11:30:00 |

| Rownam | Tim | 3 | 2012-09-01 16:00:00 |

| Joplette | ジャニス | 4 | 2012-09-01 15:00:00 |

| Butters | ジェラルド | 5 | 2012-09-02 12:30:00 |

| Tracy | バートン | 6 | 2012-09-01 15:00:00 |

| Dare | ナンシー | 7 | 2012-09-01 12:30:00 |

| Boothe | Tim | 8 | 2012-09-01 08:30:00 |

| Stibbons | Ponder | 9 | 2012-09-01 11:00:00 |

| オーウェン | チャールズ | 10 | 2012-09-01 11:00:00 |

| ジョーンズ | デビッド | 11 | 2012-09-01 09:30:00 |

| ベイカー | アン | 12 | 2012-09-01 14:30:00 |

| Farrell | Jemima | 13 | 2012-09-01 09:30:00 |

| Smith | ジャック | 14 | 2012-09-01 11:00:00 |

| Bader | フィレンツェ | 15 | 2012-09-01 10:30:00 |

| ベイカー | ティモシー | 16 | 2012-09-01 15:00:00 |

| Pinker | デビッド | 17 | 2012-09-01 08:30:00 |

| Genting | マシュー | 20 | 2012-09-01 18:00:00 |

| Mackenzie | アンナ | 21 | 2012-09-01 08:30:00 |

| Coplin | Joan | 22 | 2012-09-02 11:30:00 |

| Sarwin | Ramnaresh | 24 | 2012-09-04 11:00:00 |

| ジョーンズ | ダグラス | 26 | 2012-09-08 13:00:00 |

| Rumney | Henrietta | 27 | 2012-09-16 13:30:00 |

| Farrell | デビッド | 28 | 2012-09-18 09:00:00 |

| Worthington-Smyth | ヘンリー | 29 | 2012-09-19 09:30:00 |

| Purview | Millicent | 30 | 2012-09-19 11:30:00 |

| Tupperware | Hyacinth | 33 | 2012-09-20 08:00:00 |

| ハント | ジョン | 35 | 2012-09-23 14:00:00 |

| Crumpet | エリカ | 36 | 2012-09-27 11:30:00 |

答え:

select mems . surname , mems . firstname , mems . memid , min ( bks . starttime ) as starttime

from cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . members mems on

mems . memid = bks . memid

where starttime >= ' 2012-09-01 '

group by mems . surname , mems . firstname , mems . memid

order by mems . memid ; This answer demonstrates the use of aggregate functions on dates. MIN works exactly as you'd expect, pulling out the lowest possible date in the result set. To make this work, we need to ensure that the result set only contains dates from September onwards. We do this using the WHERE clause.

You might typically use a query like this to find a customer's next booking. You can use this by replacing the date '2012-09-01' with the function now()

Produce a list of member names, with each row containing the total member count. Order by join date.

Expected results:

| カウント | ファーストネーム | 姓 |

|---|---|---|

| 31 | ゲスト | ゲスト |

| 31 | ダレン | Smith |

| 31 | Tracy | Smith |

| 31 | Tim | Rownam |

| 31 | ジャニス | Joplette |

| 31 | ジェラルド | Butters |

| 31 | バートン | Tracy |

| 31 | ナンシー | Dare |

| 31 | Tim | Boothe |

| 31 | Ponder | Stibbons |

| 31 | チャールズ | オーウェン |

| 31 | デビッド | ジョーンズ |

| 31 | アン | ベイカー |

| 31 | Jemima | Farrell |

| 31 | ジャック | Smith |

| 31 | フィレンツェ | Bader |

| 31 | ティモシー | ベイカー |

| 31 | デビッド | Pinker |

| 31 | マシュー | Genting |

| 31 | アンナ | Mackenzie |

| 31 | Joan | Coplin |

| 31 | Ramnaresh | Sarwin |

| 31 | ダグラス | ジョーンズ |

| 31 | Henrietta | Rumney |

| 31 | デビッド | Farrell |

| 31 | ヘンリー | Worthington-Smyth |

| 31 | Millicent | Purview |

| 31 | Hyacinth | Tupperware |

| 31 | ジョン | ハント |

| 31 | エリカ | Crumpet |

| 31 | ダレン | Smith |

答え:

select count ( * ) over(), firstname, surname

from cd . members

order by joindate Using the knowledge we've built up so far, the most obvious answer to this is below. We use a subquery because otherwise SQL will require us to group by firstname and surname, producing a different result to what we're looking for.

select ( select count ( * ) from cd . members ) as count, firstname, surname

from cd . members

order by joindateThere's nothing at all wrong with this answer, but we've chosen a different approach to introduce a new concept called window functions. Window functions provide enormously powerful capabilities, in a form often more convenient than the standard aggregation functions. While this exercise is only a toy, we'll be working on more complicated examples in the near future.

Window functions operate on the result set of your (sub-)query, after the WHERE clause and all standard aggregation. They operate on a window of data. By default this is unrestricted: the entire result set, but it can be restricted to provide more useful results. For example, suppose instead of wanting the count of all members, we want the count of all members who joined in the same month as that member:

select count ( * ) over(partition by date_trunc( ' month ' ,joindate)),

firstname, surname

from cd . members

order by joindateIn this example, we partition the data by month. For each row the window function operates over, the window is any rows that have a joindate in the same month. The window function thus produces a count of the number of members who joined in that month.

You can go further. Imagine if, instead of the total number of members who joined that month, you want to know what number joinee they were that month. You can do this by adding in an ORDER BY to the window function:

select count ( * ) over(partition by date_trunc( ' month ' ,joindate) order by joindate),

firstname, surname

from cd . members

order by joindate The ORDER BY changes the window again. Instead of the window for each row being the entire partition, the window goes from the start of the partition to the current row, and not beyond. Thus, for the first member who joins in a given month, the count is 1. For the second, the count is 2, and so on.

One final thing that's worth mentioning about window functions: you can have multiple unrelated ones in the same query. Try out the query below for an example - you'll see the numbers for the members going in opposite directions! This flexibility can lead to more concise, readable, and maintainable queries.

select count ( * ) over(partition by date_trunc( ' month ' ,joindate) order by joindate asc ),

count ( * ) over(partition by date_trunc( ' month ' ,joindate) order by joindate desc ),

firstname, surname

from cd . members

order by joindateWindow functions are extraordinarily powerful, and they will change the way you write and think about SQL. Make good use of them!

Produce a monotonically increasing numbered list of members, ordered by their date of joining. Remember that member IDs are not guaranteed to be sequential.

Expected results:

| row_number | ファーストネーム | 姓 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ゲスト | ゲスト |

| 2 | ダレン | Smith |

| 3 | Tracy | Smith |

| 4 | Tim | Rownam |

| 5 | ジャニス | Joplette |

| 6 | ジェラルド | Butters |