Il s'agit d'une compilation de toutes les questions et réponses sur les exercices de PostgreSQL d'Alisdair Owen. Gardez à l'esprit que la résolution de ces problèmes vous fera aller plus loin que le simple fait de parcourir ce guide, alors assurez-vous de payer des exercices postgresql une visite.

Il est assez simple d'y aller avec les exercices: tout ce que vous avez à faire est d'ouvrir les exercices, de jeter un œil aux questions et d'essayer d'y répondre!

L'ensemble de données pour ces exercices est destiné à un country club nouvellement créé, avec un ensemble de membres, des installations telles que les courts de tennis et l'histoire de la réservation pour ces installations. Entre autres choses, le club veut comprendre comment ils peuvent utiliser leurs informations pour analyser l'utilisation / la demande des installations. Veuillez noter: Cet ensemble de données est conçu uniquement pour soutenir un éventail intéressant d'exercices, et le schéma de base de données est défectueux en plusieurs aspects - veuillez ne pas le prendre comme exemple de bonne conception. Nous allons commencer par un aperçu du tableau des membres:

CREATE TABLE cd .members

(

memid integer NOT NULL ,

surname character varying ( 200 ) NOT NULL ,

firstname character varying ( 200 ) NOT NULL ,

address character varying ( 300 ) NOT NULL ,

zipcode integer NOT NULL ,

telephone character varying ( 20 ) NOT NULL ,

recommendedby integer ,

joindate timestamp not null ,

CONSTRAINT members_pk PRIMARY KEY (memid),

CONSTRAINT fk_members_recommendedby FOREIGN KEY (recommendedby)

REFERENCES cd . members (memid) ON DELETE SET NULL

);Chaque membre a un ID (non garanti pour être séquentiel), des informations d'adresse de base, une référence au membre qui les a recommandés (le cas échéant) et un horodatage lorsqu'il a rejoint. Les adresses de l'ensemble de données sont entièrement (et irréalistes) fabriquées.

CREATE TABLE cd .facilities

(

facid integer NOT NULL ,

name character varying ( 100 ) NOT NULL ,

membercost numeric NOT NULL ,

guestcost numeric NOT NULL ,

initialoutlay numeric NOT NULL ,

monthlymaintenance numeric NOT NULL ,

CONSTRAINT facilities_pk PRIMARY KEY (facid)

);La table des installations répertorie toutes les installations réservables que possède le Country Club. Le club stocke les informations d'identité / nom, le coût de réservation à la fois des membres et des invités, le coût initial de la construction de l'installation et les coûts d'entretien mensuels estimés. Ils espèrent utiliser ces informations pour suivre la valeur financière de chaque installation.

CREATE TABLE cd .bookings

(

bookid integer NOT NULL ,

facid integer NOT NULL ,

memid integer NOT NULL ,

starttime timestamp NOT NULL ,

slots integer NOT NULL ,

CONSTRAINT bookings_pk PRIMARY KEY (bookid),

CONSTRAINT fk_bookings_facid FOREIGN KEY (facid) REFERENCES cd . facilities (facid),

CONSTRAINT fk_bookings_memid FOREIGN KEY (memid) REFERENCES cd . members (memid)

);Enfin, il y a une table de suivi des réservations d'installations. Cela stocke l'identifiant de l'installation, le membre qui a fait la réservation, le début de la réservation et le nombre de «créneaux» d'une demi-heure pour lesquels la réservation a été faite. Cette conception idiosyncrasique rendra certaines requêtes plus difficiles, mais devrait vous fournir des défis intéressants - ainsi que vous préparer à l'horreur de travailler avec des bases de données du monde réel :-).

D'accord, cela devrait être toutes les informations dont vous avez besoin. Vous pouvez sélectionner une catégorie de requête à essayer dans le menu ci-dessus, ou commencer à partir du début.

Aucun problème! Se lever et courir n'est pas trop difficile. Tout d'abord, vous aurez besoin d'une installation de PostgreSQL, que vous pouvez obtenir d'ici. Une fois que vous l'avez commencé, téléchargez le SQL.

Enfin, exécutez psql -U <username> -f clubdata.sql -d postgres -x -q pour créer la base de données `` exercices '', notez que vous pouvez constater que l'ordre de vos résultats diffère de ceux qui sont utilisés sur le site Web: ce qui utilise probablement votre postgre le paramètre C)

Lorsque vous exécutez des requêtes, vous pouvez trouver le PSQL un peu maladroit. Si c'est le cas, je recommande d'essayer Pgadmin ou les outils de développement de la base de données Eclipse.

Cette catégorie traite des bases de SQL. Il couvre sélectionné et où les clauses, les expressions de cas, les syndicats et quelques autres cotes et fins. Si vous êtes déjà éduqué à SQL, vous trouverez probablement ces exercices assez faciles. Sinon, vous devriez leur trouver un bon point pour commencer à apprendre pour les catégories les plus difficiles à venir!

Si vous avez du mal à ces questions, je recommande fortement d'apprendre SQL, par Alan Beaulieu, comme un livre concis et bien écrit sur le sujet. Si vous êtes intéressé par les principes fondamentaux des systèmes de base de données (par opposition à la façon de les utiliser), vous devez également étudier une introduction aux systèmes de base de données par CJ Date.

Comment pouvez-vous récupérer toutes les informations du tableau CD.facilities?

Résultats attendus:

| facide | nom | membre du membre | host | Initialoutlay | maintenance mensuelle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Cour de tennis 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Cour de tennis 2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Tribunal de badminton | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | Tennis de table | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Salle de massage 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Salle de massage 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Cour de squash | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Table de snooker | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Table de billard | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

Répondre:

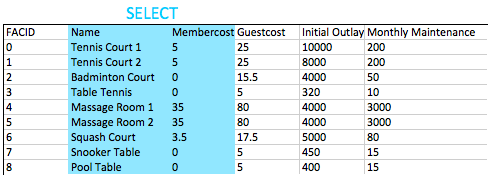

select * from cd . facilities ; L'instruction SELECT est le bloc de départ de base pour les requêtes qui lisent les informations de la base de données. Une instruction SELECT minimale est généralement composée de select [some set of columns] from [some table or group of tables] .

Dans ce cas, nous voulons toutes les informations du tableau des installations. La section From est facile - nous avons juste besoin de spécifier le tableau cd.facilities . 'CD' est le schéma du tableau - un terme utilisé pour un regroupement logique des informations connexes dans la base de données.

Ensuite, nous devons spécifier que nous voulons toutes les colonnes. Idéalement, il y a un raccourci pour «toutes les colonnes» - *. Nous pouvons l'utiliser au lieu de spécifier laborieusement tous les noms de colonnes.

Vous souhaitez imprimer une liste de toutes les installations et leur coût pour les membres. Comment récupéreriez-vous une liste de seuls noms et coûts d'installation?

Résultats attendus:

| nom | membre du membre |

|---|---|

| Cour de tennis 1 | 5 |

| Cour de tennis 2 | 5 |

| Tribunal de badminton | 0 |

| Tennis de table | 0 |

| Salle de massage 1 | 35 |

| Salle de massage 2 | 35 |

| Cour de squash | 3.5 |

| Table de snooker | 0 |

| Table de billard | 0 |

Répondre:

select name, membercost from cd . facilities ; Pour cette question, nous devons spécifier les colonnes que nous voulons. Nous pouvons le faire avec une simple liste de noms de colonnes délimitées par des virgules spécifiées pour l'instruction SELECT. Tout ce que fait la base de données est de regarder les colonnes disponibles dans la clause NUS, et de retourner celles que nous avons demandées, comme illustré ci-dessous

D'une manière générale, pour les requêtes sans throwaway, il est considéré comme souhaitable de spécifier les noms des colonnes que vous souhaitez dans vos requêtes plutôt que d'utiliser *. En effet, votre application peut ne pas être en mesure de faire face si davantage de colonnes sont ajoutées dans le tableau.

Comment pouvez-vous produire une liste d'installations qui facturent des frais aux membres?

Résultats attendus:

| facide | nom | membre du membre | host | Initialoutlay | maintenance mensuelle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Cour de tennis 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Cour de tennis 2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 4 | Salle de massage 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Salle de massage 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Cour de squash | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

Répondre:

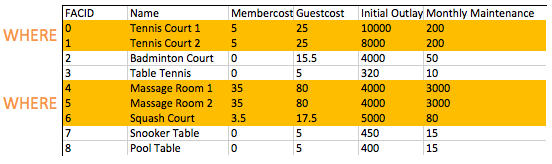

select * from cd . facilities where membercost > 0 ; La clause FROM est utilisée pour construire un ensemble de lignes candidates pour lire les résultats de. Jusqu'à présent, dans nos exemples, cet ensemble de lignes a simplement été le contenu d'une table. À l'avenir, nous explorerons l'adhésion, ce qui nous permet de créer des candidats beaucoup plus intéressants.

Une fois que nous avons construit notre ensemble de lignes de candidats, la clause WHERE nous permet de filtrer les lignes qui nous intéressent - dans ce cas, celles avec un nombre de membres de plus de zéro. Comme vous le verrez dans des exercices ultérieurs, WHERE les clauses peuvent avoir plusieurs composants combinés avec une logique booléenne - il est possible, par exemple, de rechercher des installations avec un coût supérieur à 0 et moins de 10. L'action de filtrage de la clause WHERE le tableau des installations est illustrée ci-dessous:

Comment pouvez-vous produire une liste d'installations qui facturent des frais aux membres, et ces frais sont inférieurs au 1 / 50e du coût de maintenance mensuel? Retournez le facid, le nom de l'installation, le coût des membres et l'entretien mensuel des installations en question.

Résultats attendus:

| facide | nom | membre du membre | maintenance mensuelle |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Salle de massage 1 | 35 | 3000 |

| 5 | Salle de massage 2 | 35 | 3000 |

Répondre:

select facid, name, membercost, monthlymaintenance

from cd . facilities

where

membercost > 0 and

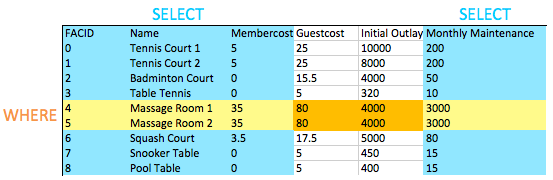

(membercost < monthlymaintenance / 50 . 0 ); La clause WHERE nous permet de filtrer les lignes qui nous intéressent - dans ce cas, celles avec un nombre de membres de plus de zéro et moins de 1 / 50e du coût de maintenance mensuel. Comme vous pouvez le voir, les salles de massage sont très chères à gérer grâce aux frais de dotation!

Lorsque nous voulons tester deux conditions ou plus, nous les utilisons AND les combinons. Nous pouvons, comme vous pouvez vous y attendre, utiliser OR tester si l'une ou l'autre d'une paire de conditions est vraie.

Vous avez peut-être remarqué qu'il s'agit de notre première requête qui combine une clause WHERE avec la sélection de colonnes spécifiques. Vous pouvez voir dans l'image ci-dessous l'effet de ceci: l'intersection des colonnes sélectionnées et des lignes sélectionnées nous donne les données à retourner. Cela peut ne pas sembler trop intéressant maintenant, mais à mesure que nous ajoutons des opérations plus complexes comme les jointures plus tard, vous verrez la simple élégance de ce comportement.

Comment pouvez-vous produire une liste de toutes les installations avec le mot «tennis» en leur nom?

Résultats attendus:

| facide | nom | membre du membre | host | Initialoutlay | maintenance mensuelle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Cour de tennis 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Cour de tennis 2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 3 | Tennis de table | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

Répondre:

select *

from cd . facilities

where

name like ' %Tennis% ' ; L'opérateur LIKE SQL fournit une correspondance de motifs simple sur les chaînes. Il est à peu près universellement implémenté et est agréable et simple à utiliser - il faut simplement une chaîne avec le% de caractère correspondant à n'importe quelle chaîne, et _ correspondant à n'importe quel caractère. Dans ce cas, nous recherchons des noms contenant le mot «tennis», donc mettre un% de chaque côté correspond à la facture.

Il existe d'autres moyens d'accomplir cette tâche: Postgres prend en charge les expressions régulières avec l'opérateur ~, par exemple. Utilisez ce qui vous fait vous sentir à l'aise, mais sachez que l'opérateur LIKE est beaucoup plus portable entre les systèmes.

Comment pouvez-vous récupérer les détails des installations avec les ID 1 et 5? Essayez de le faire sans utiliser l'opérateur OR.

Résultats attendus:

| facide | nom | membre du membre | host | Initialoutlay | maintenance mensuelle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cour de tennis 2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 5 | Salle de massage 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

Répondre:

select *

from cd . facilities

where

facid in ( 1 , 5 ); La réponse évidente à cette question est d'utiliser une WHERE où ressemble à where facid = 1 or facid = 5 . Une alternative plus facile avec un grand nombre de correspondances possibles est l'opérateur IN . L'opérateur IN prend une liste de valeurs possibles et les correspond à (dans ce cas) le facid. Si l'une des valeurs correspond, la clause Where est vraie pour cette ligne et la ligne est renvoyée.

L'opérateur IN est un bon démonstrateur précoce de l'élégance du modèle relationnel. L'argument qu'il prend n'est pas seulement une liste de valeurs - c'est en fait une table avec une seule colonne. Étant donné que les requêtes renvoient également les tables, si vous créez une requête qui renvoie une seule colonne, vous pouvez alimenter ces résultats en un opérateur IN . Pour donner un exemple de jouet:

select *

from cd . facilities

where

facid in (

select facid from cd . facilities

);Cet exemple est fonctionnellement équivalent à la simple sélection de toutes les installations, mais vous montre comment alimenter les résultats d'une requête dans une autre. La requête intérieure s'appelle une sous-requête .

Comment pouvez-vous produire une liste d'installations, chacune étiquetée comme «bon marché» ou «coûteuse» selon que leur coût de maintenance mensuel est supérieur à 100 $? Renvoyez le nom et l'entretien mensuel des installations en question.

Résultats attendus:

| nom | coût |

|---|---|

| Cour de tennis 1 | cher |

| Cour de tennis 2 | cher |

| Tribunal de badminton | bon marché |

| Tennis de table | bon marché |

| Salle de massage 1 | cher |

| Salle de massage 2 | cher |

| Cour de squash | bon marché |

| Table de snooker | bon marché |

| Table de billard | bon marché |

Répondre:

select name,

case when (monthlymaintenance > 100 ) then

' expensive '

else

' cheap '

end as cost

from cd . facilities ; Cet exercice contient quelques nouveaux concepts. Le premier est le fait que nous faisons du calcul dans la zone de la requête entre SELECT et FROM . Auparavant, nous n'avons utilisé cela que pour sélectionner des colonnes que nous voulons retourner, mais vous pouvez mettre n'importe quoi ici qui produira un seul résultat par ligne retournée - y compris les sous-requêtes.

Le deuxième nouveau concept est la déclaration CASE elle-même. CASE est effectivement comme les instructions IF / Switch dans d'autres langues, avec un formulaire comme indiqué dans la requête. Pour ajouter une option «intermédiaire», nous en insérions simplement une autre when...then section.

Enfin, il y a l'opérateur AS . Ceci est simplement utilisé pour étiqueter les colonnes ou les expressions, pour les faire afficher plus bien ou pour les rendre plus faciles à référencer lorsqu'ils sont utilisés dans le cadre d'une sous-requête.

Comment pouvez-vous produire une liste de membres qui se sont joints après le début de septembre 2012? Renvoyez le nom de la mémoire, le nom de famille, le nom de premier ordre et la jointure des membres en question.

Résultats attendus:

| souvenir | nom de famille | prénom | se joindre à |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | Sarwin | Ramnamesh | 2012-09-01 08:44:42 |

| 26 | Jones | Douglas | 2012-09-02 18:43:05 |

| 27 | Rhumney | Henrietta | 2012-09-05 08:42:35 |

| 28 | Farrell | David | 2012-09-15 08:22:05 |

| 29 | Worthington-Smyth | Henri | 2012-09-17 12:27:15 |

| 30 | Compétence | Million | 2012-09-18 19:04:01 |

| 33 | Tupperware | Jacinthe | 2012-09-18 19:32:05 |

| 35 | Chasse | John | 2012-09-19 11:32:45 |

| 36 | Crumpet | Erica | 2012-09-22 08:36:38 |

| 37 | Forgeron | Darren | 2012-09-26 18:08:45 |

Répondre:

select memid, surname, firstname, joindate

from cd . members

where joindate >= ' 2012-09-01 ' ; Ceci est notre premier aperçu des horodatages SQL. Ils sont formatés dans l'ordre de grandeur décroissant: YYYY-MM-DD HH:MM:SS.nnnnnn . Nous pouvons les comparer comme nous pourrions un horodatage Unix, bien que l'obtention des différences entre les dates soit un peu plus impliquée (et puissante!). Dans ce cas, nous venons de spécifier la partie date de l'horodatage. Cela est automatiquement jeté par Postgres dans l'horodatage complet 2012-09-01 00:00:00 .

Comment pouvez-vous produire une liste ordonnée des 10 premiers noms de famille dans le tableau des membres? La liste ne doit pas contenir de doublons.

Résultats attendus:

| nom de famille |

|---|

| Badre |

| Boulanger |

| Cabine |

| Beurres |

| Coplin |

| Crumpet |

| Oser |

| Farrell |

| INVITÉ |

| Douceur |

Répondre:

select distinct surname

from cd . members

order by surname

limit 10 ; Il y a trois nouveaux concepts ici, mais ils sont tous assez simples.

DISTINCT après SELECT supprime les lignes en double de l'ensemble de résultats. Notez que cela s'applique aux lignes : si la ligne A a plusieurs colonnes, la ligne B ne lui est égale que si les valeurs dans toutes les colonnes sont les mêmes. En règle générale, n'utilisez pas de manière DISTINCT de manière nul - il n'est pas libre de supprimer les doublons des grands ensembles de résultats de requête, alors faites-le au besoin.ORDER BY (après les clauses FROM et WHERE , près de la fin de la requête), permet d'ordonner des résultats par une colonne ou un ensemble de colonnes (la virgule séparée).LIMIT vous permet de limiter le nombre de résultats récupérés. Ceci est utile pour obtenir des résultats une page à la fois et peut être combiné avec le mot-clé OFFSET pour obtenir des pages suivantes. C'est la même approche utilisée par MySQL et est très pratique - vous pouvez malheureusement constater que ce processus est un peu plus compliqué dans les autres DB.Pour une raison quelconque, vous souhaitez une liste combinée de tous les noms de famille et tous les noms des installations. Oui, c'est un exemple artificiel :-). Produisez cette liste!

Résultats attendus:

| nom de famille |

|---|

| Cour de tennis 2 |

| Worthington-Smyth |

| Tribunal de badminton |

| Rose |

| Oser |

| Badre |

| Mackenzie |

| Crumpet |

| Salle de massage 1 |

| Cour de squash |

Répondre:

select surname

from cd . members

union

select name

from cd . facilities ; L'opérateur UNION fait ce à quoi vous pourriez vous attendre: combine les résultats de deux requêtes SQL dans une seule table. La mise en garde est que les deux résultats des deux requêtes doivent avoir le même nombre de colonnes et de types de données compatibles.

UNION supprime les lignes en double, tandis que UNION ALL ne le fait pas. Utilisez UNION ALL par défaut, sauf si vous vous souciez des résultats en double.

Vous souhaitez obtenir la date d'inscription de votre dernier membre. Comment pouvez-vous récupérer ces informations?

Résultats attendus:

| dernier |

|---|

| 2012-09-26 18:08:45 |

Répondre:

select max (joindate) as latest

from cd . members ; Il s'agit de notre première incursion dans les fonctions agrégées de SQL. Ils sont utilisés pour extraire des informations sur des groupes entiers de lignes et nous permettent de poser facilement des questions comme:

La fonction d'agrégat maximale ici est très simple: elle reçoit toutes les valeurs possibles pour la jointure et publie celle la plus importante. Il y a beaucoup plus de pouvoir pour agréger les fonctions, que vous rencontrerez dans les futurs exercices.

Vous souhaitez obtenir le premier et le nom de famille du (s) membre (s) qui s'est inscrit - pas seulement la date. Comment pouvez-vous faire cela?

Résultats attendus:

| prénom | nom de famille | se joindre à |

|---|---|---|

| Darren | Forgeron | 2012-09-26 18:08:45 |

Répondre:

select firstname, surname, joindate

from cd . members

where joindate =

( select max (joindate)

from cd . members ); Dans l'approche suggérée ci-dessus, vous utilisez une sous-requête pour savoir quelle est la jointure la plus récente. Cette sous-requête renvoie une table scalaire - c'est-à-dire une table avec une seule colonne et une seule ligne. Comme nous n'avons qu'une seule valeur, nous pouvons remplacer la sous-requête partout où nous pourrions mettre une seule valeur constante. Dans ce cas, nous l'utilisons pour compléter la clause WHERE une requête pour trouver un membre donné.

Vous pourriez espérer que vous pourriez faire quelque chose comme ci-dessous:

select firstname, surname, max (joindate)

from cd . members Malheureusement, cela ne fonctionne pas. La fonction MAX ne restreint pas les lignes comme la clause WHERE - elle prend simplement un tas de valeurs et renvoie la plus grande. La base de données est ensuite laissée à se demander comment appuyer une longue liste de noms avec la date de jointure unique qui est sortie de la fonction maximale et échoue. Au lieu de cela, vous devez dire «Trouvez-moi la ou les lignes qui ont une date de jointure qui est la même que la date de jointure maximale».

Comme mentionné par l'indice, il existe d'autres moyens de faire ce travail - un exemple est ci-dessous. Dans cette approche, plutôt que de découvrir explicitement quelle est la dernière date de jointure, nous commandons simplement notre tableau de membres dans l'ordre descendant de la date de jointure, et choisissons le premier. Notez que cette approche ne couvre pas l'éventualité extrêmement improbable de deux personnes qui se joignent exactement au même moment :-).

select firstname, surname, joindate

from cd . members

order by joindate desc

limit 1 ;Cette catégorie traite principalement d'un concept fondamental dans les systèmes de base de données relationnels: la jonction. La jointure vous permet de combiner des informations connexes à partir de plusieurs tables pour répondre à une question. Ce n'est pas seulement bénéfique pour la facilité de requête: un manque de capacité de jointure encourage la dénormalisation des données, ce qui augmente la complexité de la maintenance de vos données cohérentes en interne.

Ce sujet couvre les joints intérieurs, extérieurs et auto, ainsi que de passer un peu de temps sur des sous-requêtes (requêtes dans les requêtes). Si vous avez du mal à ces questions, je recommande fortement d'apprendre SQL, par Alan Beaulieu, comme un livre concis et bien écrit sur le sujet.

Comment pouvez-vous produire une liste des heures de début pour les réservations par des membres nommés «David Farrell»?

Résultats attendus:

| durée |

|---|

| 2012-09-18 09:00:00 |

| 2012-09-18 17:30:00 |

| 2012-09-18 13:30:00 |

| 2012-09-18 20:00:00 |

| 2012-09-19 09:30:00 |

| 2012-09-19 15:00:00 |

| 2012-09-19 12:00:00 |

| 2012-09-20 15:30:00 |

| 2012-09-20 11:30:00 |

| 2012-09-20 14:00:00 |

Répondre:

select bks . starttime

from

cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . members mems

on mems . memid = bks . memid

where

mems . firstname = ' David '

and mems . surname = ' Farrell ' ; Le type de jointure le plus couramment utilisé est la INNER JOIN . Ce que cela fait, c'est combiner deux tables en fonction d'une expression de jointure - dans ce cas, pour chaque ID de membre dans le tableau des membres, nous recherchons des valeurs correspondantes dans le tableau des réservations. Lorsque nous trouvons une correspondance, une ligne combinant les valeurs pour chaque table est renvoyée. Notez que nous avons donné à chaque tableau un alias (BKS et MEMS). Ceci est utilisé pour deux raisons: premièrement, c'est pratique, et deuxièmement, nous pourrions nous joindre au même tableau plusieurs fois, nous obligeant à distinguer les colonnes de chaque fois que le tableau a été joint.

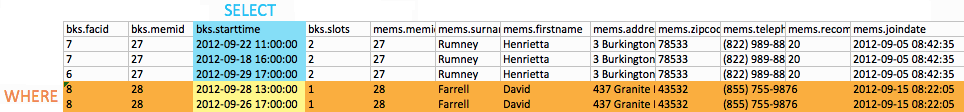

Ignorons notre sélection et où les clauses pour l'instant, et concentrons-nous sur ce que la FROM produit. Dans tous nos exemples précédents, FROM vient d'être une table simple. Qu'est-ce que c'est maintenant? Une autre table! Cette fois, il est produit comme un composite de réservations et de membres. Vous pouvez voir un sous-ensemble de la sortie de la jointure ci-dessous:

Pour chaque membre de la table des membres, la jointure a trouvé tous les ID de membre correspondant dans le tableau des réservations. Pour chaque match, il est ensuite produit une ligne combinant la ligne de la table des membres et la ligne de la table de réservations.

De toute évidence, il s'agit de trop d'informations en soi, et toute question utile voudra la filtrer. Dans notre requête, nous utilisons le début de la clause SELECT pour choisir les colonnes et la clause WHERE choisir les lignes, comme illustré ci-dessous:

C'est tout ce dont nous avons besoin pour trouver les réservations de David! En général, je vous encourage à vous rappeler que la sortie de la clause FROM est essentiellement une grande table dont vous filtrez ensuite les informations. Cela peut sembler inefficace - mais ne vous inquiétez pas, sous les couvertures, la base de données se comportera beaucoup plus intelligemment :-).

Une dernière note: il existe deux syntaxes différentes pour les jointures intérieures. Je vous ai montré celui que je préfère, que je trouve plus cohérent avec d'autres types de jointures. Vous verrez généralement une syntaxe différente, illustrée ci-dessous:

select bks . starttime

from

cd . bookings bks,

cd . members mems

where

mems . firstname = ' David '

and mems . surname = ' Farrell '

and mems . memid = bks . memid ;Ceci est fonctionnellement exactement la même que la réponse approuvée. Si vous vous sentez plus à l'aise avec cette syntaxe, n'hésitez pas à l'utiliser!

Comment pouvez-vous produire une liste des heures de début pour les réservations pour les courts de tennis, pour la date «2012-09-21»? Renvoyez une liste des appariements de début et de nom de l'installation, commandés par le temps.

Résultats attendus:

| commencer | nom |

|---|---|

| 2012-09-21 08:00:00 | Cour de tennis 1 |

| 2012-09-21 08:00:00 | Cour de tennis 2 |

| 2012-09-21 09:30:00 | Cour de tennis 1 |

| 2012-09-21 10:00:00 | Cour de tennis 2 |

| 2012-09-21 11:30:00 | Cour de tennis 2 |

| 2012-09-21 12:00:00 | Cour de tennis 1 |

| 2012-09-21 13:30:00 | Cour de tennis 1 |

| 2012-09-21 14:00:00 | Cour de tennis 2 |

| 2012-09-21 15:30:00 | Cour de tennis 1 |

| 2012-09-21 16:00:00 | Cour de tennis 2 |

| 2012-09-21 17:00:00 | Cour de tennis 1 |

| 2012-09-21 18:00:00 | Cour de tennis 2 |

Répondre:

select bks . starttime as start, facs . name as name

from

cd . facilities facs

inner join cd . bookings bks

on facs . facid = bks . facid

where

facs . facid in ( 0 , 1 ) and

bks . starttime >= ' 2012-09-21 ' and

bks . starttime < ' 2012-09-22 '

order by bks . starttime ; Ceci est une autre requête INNER JOIN , bien qu'elle ait un peu plus de complexité dedans! La FROM de la requête est facile - nous rejoignons simplement les installations et les tables de réservations sur le facid. Cela produit un tableau où, pour chaque ligne dans les réservations, nous avons joint des informations détaillées sur l'installation réservée.

Sur le composant WHERE la requête. Les chèques de démarrage sont assez explicites - nous nous assurons que toutes les réservations commencent entre les dates spécifiées. Étant donné que nous ne sommes intéressés que par les courts de tennis, nous utilisons également l'opérateur IN pour dire au système de base de données de ne nous rendre que des ID de l'installation 0 ou 1 - les identifiants des tribunaux. Il existe d'autres moyens d'exprimer ceci: nous aurions pu utiliser where facs.facid = 0 or facs.facid = 1 , ou même where facs.name like 'Tennis%' .

Le reste est assez simple: nous SELECT les colonnes qui nous intéressent et ORDER BY l'heure de début.

Comment pouvez-vous publier une liste de tous les membres qui ont recommandé un autre membre? Assurez-vous qu'il n'y a pas de doublons dans la liste, et que les résultats sont ordonnés par (nom de famille, premier nom).

Résultats attendus:

| prénom | nom de famille |

|---|---|

| Florence | Badre |

| Timothée | Boulanger |

| Gerald | Beurres |

| Jemima | Farrell |

| Matthieu | Douceur |

| David | Jones |

| Janice | Joplette |

| Million | Compétence |

| Tim | Rownam |

| Darren | Forgeron |

| Tracy | Forgeron |

| Réfléchir | Stibbons |

| Burton | Tracy |

Répondre:

select distinct recs . firstname as firstname, recs . surname as surname

from

cd . members mems

inner join cd . members recs

on recs . memid = mems . recommendedby

order by surname, firstname; Voici un concept que certaines personnes trouvent déroutant: vous pouvez rejoindre un tableau à lui-même! Ceci est vraiment utile si vous avez des colonnes qui font référence aux données dans le même tableau, comme nous le faisons avec recommandé dans CD.Members.

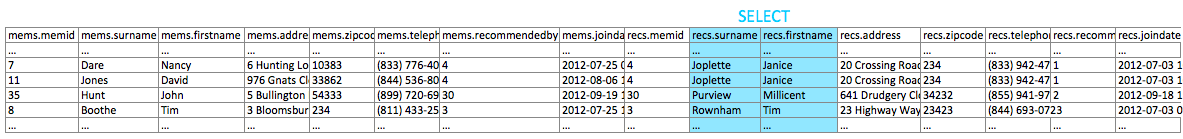

Si vous avez du mal à visualiser cela, n'oubliez pas que cela fonctionne tout comme toute autre jointure intérieure. Notre jointure prend chaque ligne dans des membres qui a une valeur recommandée et regarde à nouveau dans les membres pour la ligne qui a un ID de membre correspondant. Il génère ensuite une ligne de sortie combinant les deux entrées de membres. Cela ressemble au diagramme ci-dessous:

Notez que même si nous pourrions avoir deux colonnes de famille dans l'ensemble de sortie, ils peuvent être distingués par leurs alias de table. Une fois que nous avons sélectionné les colonnes que nous voulons, nous utilisons simplement DISTINCT pour nous assurer qu'il n'y a pas de doublons.

Comment pouvez-vous publier une liste de tous les membres, y compris la personne qui les a recommandés (le cas échéant)? Assurez-vous que les résultats sont ordonnés par (nom de famille, premier nom).

Résultats attendus:

| nom | nom de mèmes | nom de recfn | recsname |

|---|---|---|---|

| Florence | Badre | Réfléchir | Stibbons |

| Anne | Boulanger | Réfléchir | Stibbons |

| Timothée | Boulanger | Jemima | Farrell |

| Tim | Cabine | Tim | Rownam |

| Gerald | Beurres | Darren | Forgeron |

| Joan | Coplin | Timothée | Boulanger |

| Erica | Crumpet | Tracy | Forgeron |

| Nancy | Oser | Janice | Joplette |

| David | Farrell | ||

| Jemima | Farrell | ||

| INVITÉ | INVITÉ | ||

| Matthieu | Douceur | Gerald | Beurres |

| John | Chasse | Million | Compétence |

| David | Jones | Janice | Joplette |

| Douglas | Jones | David | Jones |

| Janice | Joplette | Darren | Forgeron |

| Anna | Mackenzie | Darren | Forgeron |

| Charles | Owen | Darren | Forgeron |

| David | Rose | Jemima | Farrell |

| Million | Compétence | Tracy | Forgeron |

| Tim | Rownam | ||

| Henrietta | Rhumney | Matthieu | Douceur |

| Ramnamesh | Sarwin | Florence | Badre |

| Darren | Forgeron | ||

| Darren | Forgeron | ||

| Jack | Forgeron | Darren | Forgeron |

| Tracy | Forgeron | ||

| Réfléchir | Stibbons | Burton | Tracy |

| Burton | Tracy | ||

| Jacinthe | Tupperware | ||

| Henri | Worthington-Smyth | Tracy | Forgeron |

Répondre:

select mems . firstname as memfname, mems . surname as memsname, recs . firstname as recfname, recs . surname as recsname

from

cd . members mems

left outer join cd . members recs

on recs . memid = mems . recommendedby

order by memsname, memfname; Présentez un autre nouveau concept: la LEFT OUTER JOIN . Ceux-ci sont mieux expliqués par la façon dont ils diffèrent des jointures intérieures. Les jointures intérieures prennent une table à gauche et une table droite, et recherchez des lignes assorties en fonction d'une condition de jointure ( ON ). Lorsque la condition est satisfaite, une ligne jointe est produite. Une LEFT OUTER JOIN fonctionne de manière similaire, sauf que si une ligne donnée sur la table gauche ne correspond à rien, elle produit toujours une ligne de sortie. Cette ligne de sortie se compose de la ligne de table gauche et d'un tas de NULLS à la place de la ligne de table droite.

Ceci est utile dans des situations comme cette question, où nous voulons produire une sortie avec des données facultatives. Nous voulons les noms de tous les membres et le nom de leur recommandateur si cette personne existe . Vous ne pouvez pas exprimer cela correctement avec une jointure intérieure.

Comme vous l'avez peut-être deviné, il y a aussi d'autres jointures extérieures. La RIGHT OUTER JOIN ressemble beaucoup à la LEFT OUTER JOIN , sauf que le côté gauche de l'expression est celui qui contient les données facultatives. La FULL OUTER JOIN rarement utilisée traite les deux côtés de l'expression comme facultative.

Comment pouvez-vous produire une liste de tous les membres qui ont utilisé un court de tennis? Incluez dans votre sortie le nom du tribunal et le nom du membre formaté comme une seule colonne. Assurez-vous aucune donnée en double et commandez par le nom du membre.

Résultats attendus:

| membre | facilité |

|---|---|

| Anne Baker | Cour de tennis 2 |

| Anne Baker | Cour de tennis 1 |

| Burton Tracy | Cour de tennis 2 |

| Burton Tracy | Cour de tennis 1 |

| Charles Owen | Cour de tennis 2 |

| Charles Owen | Cour de tennis 1 |

| Darren Smith | Cour de tennis 2 |

| David Farrell | Cour de tennis 2 |

| David Farrell | Cour de tennis 1 |

| David Jones | Cour de tennis 1 |

| David Jones | Cour de tennis 2 |

| David Pinker | Cour de tennis 1 |

| Douglas Jones | Cour de tennis 1 |

| Erica Crumpet | Cour de tennis 1 |

| Florence Bader | Cour de tennis 1 |

| Florence Bader | Cour de tennis 2 |

| Invité | Cour de tennis 2 |

| Invité | Cour de tennis 1 |

| Beurres Gerald | Cour de tennis 1 |

| Beurres Gerald | Cour de tennis 2 |

| Henrietta Rumney | Cour de tennis 2 |

| Jack Smith | Cour de tennis 1 |

| Jack Smith | Cour de tennis 2 |

| Janice Joplette | Cour de tennis 1 |

| Janice Joplette | Cour de tennis 2 |

| Jemima Farrell | Cour de tennis 2 |

| Jemima Farrell | Cour de tennis 1 |

| Joan Coplin | Cour de tennis 1 |

| John Hunt | Cour de tennis 1 |

| John Hunt | Cour de tennis 2 |

| Matthew Genting | Cour de tennis 1 |

| Mincent | Cour de tennis 2 |

| Nancy Dare | Cour de tennis 2 |

| Nancy Dare | Cour de tennis 1 |

| Ponder Stibbons | Cour de tennis 2 |

| Ponder Stibbons | Cour de tennis 1 |

| Ramnaresh Sarwin | Cour de tennis 2 |

| Ramnaresh Sarwin | Cour de tennis 1 |

| Tim Boothe | Cour de tennis 1 |

| Tim Boothe | Cour de tennis 2 |

| Tim Rownam | Cour de tennis 1 |

| Tim Rownam | Cour de tennis 2 |

| Timothy Baker | Cour de tennis 2 |

| Timothy Baker | Cour de tennis 1 |

| Tracy Smith | Cour de tennis 2 |

| Tracy Smith | Cour de tennis 1 |

Répondre:

select distinct mems . firstname || ' ' || mems . surname as member, facs . name as facility

from

cd . members mems

inner join cd . bookings bks

on mems . memid = bks . memid

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

where

bks . facid in ( 0 , 1 )

order by member Cet exercice est en grande partie une application plus complexe de ce que vous avez appris dans les questions antérieures. C'est aussi la première fois que nous utilisons plus d'une jointure, ce qui peut être un peu déroutant pour certains. Lors de la lecture des expressions de jointure, n'oubliez pas qu'une jointure est effectivement une fonction qui prend deux tables, l'une étiquetée la table gauche et l'autre de droite. C'est facile à visualiser avec une seule jointure dans la requête, mais un peu plus déroutant avec deux.

Notre deuxième INNER JOIN dans cette requête a un côté droit de CD.facilities. C'est assez facile à saisir. Le gauche, cependant, est le tableau renvoyé en rejoignant CD.Members à CD.Bookings. Il est important de souligner ceci: le modèle relationnel est une question de tableaux. La sortie de toute jointure est un autre tableau. La sortie d'une requête est un tableau. Les listes à colonnes simples sont des tables. Une fois que vous avez compris cela, vous avez compris la beauté fondamentale du modèle.

En tant que note finale, nous introduisons une nouvelle chose ici: le || L'opérateur est utilisé pour concaténer les chaînes.

Comment pouvez-vous produire une liste de réservations le jour de 2012-09-14 qui coûtera plus de 30 $ au membre (ou à l'invité)? N'oubliez pas que les invités ont des coûts différents pour les membres (les coûts énumérés sont par une demi-heure «créneau»), et l'utilisateur invité est toujours ID 0. Inclure dans votre sortie le nom de l'installation, le nom du membre formaté en une seule colonne et le coût. Commandez par coût descendant et n'utilisez aucune sous-questionnaire.

Résultats attendus:

| membre | facilité | coût |

|---|---|---|

| Invité | Salle de massage 2 | 320 |

| Invité | Salle de massage 1 | 160 |

| Invité | Salle de massage 1 | 160 |

| Invité | Salle de massage 1 | 160 |

| Invité | Cour de tennis 2 | 150 |

| Jemima Farrell | Salle de massage 1 | 140 |

| Invité | Cour de tennis 1 | 75 |

| Invité | Cour de tennis 2 | 75 |

| Invité | Cour de tennis 1 | 75 |

| Matthew Genting | Salle de massage 1 | 70 |

| Florence Bader | Salle de massage 2 | 70 |

| Invité | Cour de squash | 70.0 |

| Jemima Farrell | Salle de massage 1 | 70 |

| Ponder Stibbons | Salle de massage 1 | 70 |

| Burton Tracy | Salle de massage 1 | 70 |

| Jack Smith | Salle de massage 1 | 70 |

| Invité | Cour de squash | 35.0 |

| Invité | Cour de squash | 35.0 |

Répondre:

select mems . firstname || ' ' || mems . surname as member,

facs . name as facility,

case

when mems . memid = 0 then

bks . slots * facs . guestcost

else

bks . slots * facs . membercost

end as cost

from

cd . members mems

inner join cd . bookings bks

on mems . memid = bks . memid

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

where

bks . starttime >= ' 2012-09-14 ' and

bks . starttime < ' 2012-09-15 ' and (

( mems . memid = 0 and bks . slots * facs . guestcost > 30 ) or

( mems . memid != 0 and bks . slots * facs . membercost > 30 )

)

order by cost desc ; C'est un peu compliqué! Bien que sa logique plus complexe que nous ayons utilisée précédemment, il n'y a pas énormément de choses à remarquer. La clause WHERE restreint notre production à des lignes suffisamment coûteuses le 2012-09-14, en se souvenant de distinguer les invités et les autres. Nous utilisons ensuite une instruction CASE dans les sélections de colonnes pour produire le coût correct pour le membre ou l'invité.

Comment pouvez-vous publier une liste de tous les membres, y compris l'individu qui les a recommandés (le cas échéant), sans utiliser de joints? Assurez-vous qu'il n'y a pas de doublons dans la liste, et que chaque appariement de nom de nom + FirstName + de famille est formaté sous forme de colonne et ordonné.

Résultats attendus:

| membre | recommandation |

|---|---|

| Anna Mackenzie | Darren Smith |

| Anne Baker | Ponder Stibbons |

| Burton Tracy | |

| Charles Owen | Darren Smith |

| Darren Smith | |

| David Farrell | |

| David Jones | Janice Joplette |

| David Pinker | Jemima Farrell |

| Douglas Jones | David Jones |

| Erica Crumpet | Tracy Smith |

| Florence Bader | Ponder Stibbons |

| Invité | |

| Beurres Gerald | Darren Smith |

| Henrietta Rumney | Matthew Genting |

| Henry Worthington-Smyth | Tracy Smith |

| Tupperware de jacinthe | |

| Jack Smith | Darren Smith |

| Janice Joplette | Darren Smith |

| Jemima Farrell | |

| Joan Coplin | Timothy Baker |

| John Hunt | Mincent |

| Matthew Genting | Beurres Gerald |

| Mincent | Tracy Smith |

| Nancy Dare | Janice Joplette |

| Ponder Stibbons | Burton Tracy |

| Ramnaresh Sarwin | Florence Bader |

| Tim Boothe | Tim Rownam |

| Tim Rownam | |

| Timothy Baker | Jemima Farrell |

| Tracy Smith |

Répondre:

select distinct mems . firstname || ' ' || mems . surname as member,

( select recs . firstname || ' ' || recs . surname as recommender

from cd . members recs

where recs . memid = mems . recommendedby

)

from

cd . members mems

order by member; Cet exercice marque l'introduction de sous-requêtes. Les sous-questionnaires sont, comme son nom l'indique, les requêtes dans une requête. They're commonly used with aggregates, to answer questions like 'get me all the details of the member who has spent the most hours on Tennis Court 1'.

In this case, we're simply using the subquery to emulate an outer join. For every value of member, the subquery is run once to find the name of the individual who recommended them (if any). A subquery that uses information from the outer query in this way (and thus has to be run for each row in the result set) is known as a correlated subquery .

The Produce a list of costly bookings exercise contained some messy logic: we had to calculate the booking cost in both the WHERE clause and the CASE statement. Try to simplify this calculation using subqueries. For reference, the question was:

How can you produce a list of bookings on the day of 2012-09-14 which will cost the member (or guest) more than $30? Remember that guests have different costs to members (the listed costs are per half-hour 'slot'), and the guest user is always ID 0. Include in your output the name of the facility, the name of the member formatted as a single column, and the cost. Order by descending cost.

Expected results:

| membre | facilité | coût |

|---|---|---|

| GUEST GUEST | Massage Room 2 | 320 |

| GUEST GUEST | Massage Room 1 | 160 |

| GUEST GUEST | Massage Room 1 | 160 |

| GUEST GUEST | Massage Room 1 | 160 |

| GUEST GUEST | Tennis Court 2 | 150 |

| Jemima Farrell | Massage Room 1 | 140 |

| GUEST GUEST | Tennis Court 1 | 75 |

| GUEST GUEST | Tennis Court 2 | 75 |

| GUEST GUEST | Tennis Court 1 | 75 |

| Matthew Genting | Massage Room 1 | 70 |

| Florence Bader | Massage Room 2 | 70 |

| GUEST GUEST | Squash Court | 70.0 |

| Jemima Farrell | Massage Room 1 | 70 |

| Ponder Stibbons | Massage Room 1 | 70 |

| Burton Tracy | Massage Room 1 | 70 |

| Jack Smith | Massage Room 1 | 70 |

| GUEST GUEST | Squash Court | 35.0 |

| GUEST GUEST | Squash Court | 35.0 |

Répondre:

select member, facility, cost from (

select

mems . firstname || ' ' || mems . surname as member,

facs . name as facility,

case

when mems . memid = 0 then

bks . slots * facs . guestcost

else

bks . slots * facs . membercost

end as cost

from

cd . members mems

inner join cd . bookings bks

on mems . memid = bks . memid

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

where

bks . starttime >= ' 2012-09-14 ' and

bks . starttime < ' 2012-09-15 '

) as bookings

where cost > 30

order by cost desc ; This answer provides a mild simplification to the previous iteration: in the no-subquery version, we had to calculate the member or guest's cost in both the WHERE clause and the CASE statement. In our new version, we produce an inline query that calculates the total booking cost for us, allowing the outer query to simply select the bookings it's looking for. For reference, you may also see subqueries in the FROM clause referred to as inline views .

Querying data is all well and good, but at some point you're probably going to want to put data into your database! This section deals with inserting, updating, and deleting information. Operations that alter your data like this are collectively known as Data Manipulation Language, or DML.

In previous sections, we returned to you the results of the query you've performed. Since modifications like the ones we're making in this section don't return any query results, we instead show you the updated content of the table you're supposed to be working on. You can compare this with the table shown in 'Expected Results' to see how you've done.

If you struggle with these questions, I strongly recommend Learning SQL, by Alan Beaulieu.

The club is adding a new facility - a spa. We need to add it into the facilities table. Use the following values:

Expected results:

| facid | nom | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | Tennis de table | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Table de billard | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

| 9 | Spa | 20 | 30 | 100000 | 800 |

Répondre:

insert into cd . facilities

(facid, name, membercost, guestcost, initialoutlay, monthlymaintenance)

values ( 9 , ' Spa ' , 20 , 30 , 100000 , 800 ); INSERT INTO ... VALUES is the simplest way to insert data into a table. There's not a whole lot to discuss here: VALUES is used to construct a row of data, which the INSERT statement inserts into the table. It's a simple as that.

You can see that there's two sections in parentheses. The first is part of the INSERT statement, and specifies the columns that we're providing data for. The second is part of VALUES , and specifies the actual data we want to insert into each column.

If we're inserting data into every column of the table, as in this example, explicitly specifying the column names is optional. As long as you fill in data for all columns of the table, in the order they were defined when you created the table, you can do something like the following:

insert into cd . facilities values ( 9 , ' Spa ' , 20 , 30 , 100000 , 800 );Generally speaking, for SQL that's going to be reused I tend to prefer being explicit and specifying the column names.

In the previous exercise, you learned how to add a facility. Now you're going to add multiple facilities in one command. Use the following values:

Expected results:

| facid | nom | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | Tennis de table | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Table de billard | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

| 9 | Spa | 20 | 30 | 100000 | 800 |

| 10 | Squash Court 2 | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

Répondre:

insert into cd . facilities

(facid, name, membercost, guestcost, initialoutlay, monthlymaintenance)

values

( 9 , ' Spa ' , 20 , 30 , 100000 , 800 ),

( 10 , ' Squash Court 2 ' , 3 . 5 , 17 . 5 , 5000 , 80 ); VALUES can be used to generate more than one row to insert into a table, as seen in this example. Hopefully it's clear what's going on here: the output of VALUES is a table, and that table is copied into cd.facilities, the table specified in the INSERT command.

While you'll most commonly see VALUES when inserting data, Postgres allows you to use VALUES wherever you might use a SELECT . This makes sense: the output of both commands is a table, it's just that VALUES is a bit more ergonomic when working with constant data.

Similarly, it's possible to use SELECT wherever you see a VALUES . This means that you can INSERT the results of a SELECT . Par exemple:

insert into cd . facilities

(facid, name, membercost, guestcost, initialoutlay, monthlymaintenance)

SELECT 9 , ' Spa ' , 20 , 30 , 100000 , 800

UNION ALL

SELECT 10 , ' Squash Court 2 ' , 3 . 5 , 17 . 5 , 5000 , 80 ; In later exercises you'll see us using INSERT ... SELECT to generate data to insert based on the information already in the database.

Let's try adding the spa to the facilities table again. This time, though, we want to automatically generate the value for the next facid, rather than specifying it as a constant. Use the following values for everything else:

Expected results:

| facid | nom | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 5 | 25 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | Tennis de table | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Table de billard | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

| 9 | Spa | 20 | 30 | 100000 | 800 |

Répondre:

insert into cd . facilities

(facid, name, membercost, guestcost, initialoutlay, monthlymaintenance)

select ( select max (facid) from cd . facilities ) + 1 , ' Spa ' , 20 , 30 , 100000 , 800 ; In the previous exercises we used VALUES to insert constant data into the facilities table. Here, though, we have a new requirement: a dynamically generated ID. This gives us a real quality of life improvement, as we don't have to manually work out what the current largest ID is: the SQL command does it for us.

Since the VALUES clause is only used to supply constant data, we need to replace it with a query instead. The SELECT statement is fairly simple: there's an inner subquery that works out the next facid based on the largest current id, and the rest is just constant data. The output of the statement is a row that we insert into the facilities table.

While this works fine in our simple example, it's not how you would generally implement an incrementing ID in the real world. Postgres provides SERIAL types that are auto-filled with the next ID when you insert a row. As well as saving us effort, these types are also safer: unlike the answer given in this exercise, there's no need to worry about concurrent operations generating the same ID.

We made a mistake when entering the data for the second tennis court. The initial outlay was 10000 rather than 8000: you need to alter the data to fix the error.

Expected results:

| facid | nom | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | Tennis de table | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Table de billard | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

Répondre:

update cd . facilities

set initialoutlay = 10000

where facid = 1 ; The UPDATE statement is used to alter existing data. If you're familiar with SELECT queries, it's pretty easy to read: the WHERE clause works in exactly the same fashion, allowing us to filter the set of rows we want to work with. These rows are then modified according to the specifications of the SET clause: in this case, setting the initial outlay.

The WHERE clause is extremely important. It's easy to get it wrong or even omit it, with disastrous results. Consider the following command:

update cd . facilities

set initialoutlay = 10000 ; There's no WHERE clause to filter for the rows we're interested in. The result of this is that the update runs on every row in the table! This is rarely what we want to happen.

We want to increase the price of the tennis courts for both members and guests. Update the costs to be 6 for members, and 30 for guests.

| facid | nom | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 6 | 30 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 6 | 30 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | Tennis de table | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Table de billard | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

Répondre:

update cd . facilities

set

membercost = 6 ,

guestcost = 30

where facid in ( 0 , 1 ); The SET clause accepts a comma separated list of values that you want to update.

We want to alter the price of the second tennis court so that it costs 10% more than the first one. Try to do this without using constant values for the prices, so that we can reuse the statement if we want to.

Expected results:

| facid | nom | membercost | guestcost | initialoutlay | monthlymaintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tennis Court 1 | 5 | 25 | 10000 | 200 |

| 1 | Tennis Court 2 | 5.5 | 27.5 | 8000 | 200 |

| 2 | Badminton Court | 0 | 15.5 | 4000 | 50 |

| 3 | Tennis de table | 0 | 5 | 320 | 10 |

| 4 | Massage Room 1 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 5 | Massage Room 2 | 35 | 80 | 4000 | 3000 |

| 6 | Squash Court | 3.5 | 17.5 | 5000 | 80 |

| 7 | Snooker Table | 0 | 5 | 450 | 15 |

| 8 | Table de billard | 0 | 5 | 400 | 15 |

Répondre:

update cd . facilities facs

set

membercost = ( select membercost * 1 . 1 from cd . facilities where facid = 0 ),

guestcost = ( select guestcost * 1 . 1 from cd . facilities where facid = 0 )

where facs . facid = 1 ; Updating columns based on calculated data is not too intrinsically difficult: we can do so pretty easily using subqueries. You can see this approach in our selected answer.

As the number of columns we want to update increases, standard SQL can start to get pretty awkward: you don't want to be specifying a separate subquery for each of 15 different column updates. Postgres provides a nonstandard extension to SQL called UPDATE...FROM that addresses this: it allows you to supply a FROM clause to generate values for use in the SET clause. Example below:

update cd . facilities facs

set

membercost = facs2 . membercost * 1 . 1 ,

guestcost = facs2 . guestcost * 1 . 1

from ( select * from cd . facilities where facid = 0 ) facs2

where facs . facid = 1 ;As part of a clearout of our database, we want to delete all bookings from the cd.bookings table. How can we accomplish this?

Expected results:

| bookid | facid | memid | starttime | slots |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Répondre:

delete from cd . bookings ; The DELETE statement does what it says on the tin: deletes rows from the table. Here, we show the command in its simplest form, with no qualifiers. In this case, it deletes everything from the table. Obviously, you should be careful with your deletes and make sure they're always limited - we'll see how to do that in the next exercise.

An alternative to unqualified DELETE s is the following:

truncate cd . bookings ; TRUNCATE also deletes everything in the table, but does so using a quicker underlying mechanism. It's not perfectly safe in all circumstances, though, so use judiciously. When in doubt, use DELETE .

We want to remove member 37, who has never made a booking, from our database. How can we achieve that?

Expected results:

| memid | nom de famille | prénom | adresse | code postal | téléphone | recommendedby | joindate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | INVITÉ | INVITÉ | INVITÉ | 0 | (000) 000-0000 | 2012-07-01 00:00:00 | |

| 1 | Forgeron | Darren | 8 Bloomsbury Close, Boston | 4321 | 555-555-5555 | 2012-07-02 12:02:05 | |

| 2 | Forgeron | Tracy | 8 Bloomsbury Close, New York | 4321 | 555-555-5555 | 2012-07-02 12:08:23 | |

| 3 | Rownam | Tim | 23 Highway Way, Boston | 23423 | (844) 693-0723 | 2012-07-03 09:32:15 | |

| 4 | Joplette | Janice | 20 Crossing Road, New York | 234 | (833) 942-4710 | 1 | 2012-07-03 10:25:05 |

| 5 | Butters | Gerald | 1065 Huntingdon Avenue, Boston | 56754 | (844) 078-4130 | 1 | 2012-07-09 10:44:09 |

| 6 | Tracy | Burton | 3 Tunisia Drive, Boston | 45678 | (822) 354-9973 | 2012-07-15 08:52:55 | |

| 7 | Oser | Nancy | 6 Hunting Lodge Way, Boston | 10383 | (833) 776-4001 | 4 | 2012-07-25 08:59:12 |

| 8 | Boothe | Tim | 3 Bloomsbury Close, Reading, 00234 | 234 | (811) 433-2547 | 3 | 2012-07-25 16:02:35 |

| 9 | Stibbons | Réfléchir | 5 Dragons Way, Winchester | 87630 | (833) 160-3900 | 6 | 2012-07-25 17:09:05 |

| 10 | Owen | Charles | 52 Cheshire Grove, Winchester, 28563 | 28563 | (855) 542-5251 | 1 | 2012-08-03 19:42:37 |

| 11 | Jones | David | 976 Gnats Close, Reading | 33862 | (844) 536-8036 | 4 | 2012-08-06 16:32:55 |

| 12 | Boulanger | Anne | 55 Powdery Street, Boston | 80743 | 844-076-5141 | 9 | 2012-08-10 14:23:22 |

| 13 | Farrell | Jemima | 103 Firth Avenue, North Reading | 57392 | (855) 016-0163 | 2012-08-10 14:28:01 | |

| 14 | Forgeron | Jack | 252 Binkington Way, Boston | 69302 | (822) 163-3254 | 1 | 2012-08-10 16:22:05 |

| 15 | Badre | Florence | 264 Ursula Drive, Westford | 84923 | (833) 499-3527 | 9 | 2012-08-10 17:52:03 |

| 16 | Boulanger | Timothée | 329 James Street, Reading | 58393 | 833-941-0824 | 13 | 2012-08-15 10:34:25 |

| 17 | Pinker | David | 5 Impreza Road, Boston | 65332 | 811 409-6734 | 13 | 2012-08-16 11:32:47 |

| 20 | Genting | Matthieu | 4 Nunnington Place, Wingfield, Boston | 52365 | (811) 972-1377 | 5 | 2012-08-19 14:55:55 |

| 21 | Mackenzie | Anna | 64 Perkington Lane, Reading | 64577 | (822) 661-2898 | 1 | 2012-08-26 09:32:05 |

| 22 | Coplin | Joan | 85 Bard Street, Bloomington, Boston | 43533 | (822) 499-2232 | 16 | 2012-08-29 08:32:41 |

| 24 | Sarwin | Ramnaresh | 12 Bullington Lane, Boston | 65464 | (822) 413-1470 | 15 | 2012-09-01 08:44:42 |

| 26 | Jones | Douglas | 976 Gnats Close, Reading | 11986 | 844 536-8036 | 11 | 2012-09-02 18:43:05 |

| 27 | Rumney | Henrietta | 3 Burkington Plaza, Boston | 78533 | (822) 989-8876 | 20 | 2012-09-05 08:42:35 |

| 28 | Farrell | David | 437 Granite Farm Road, Westford | 43532 | (855) 755-9876 | 2012-09-15 08:22:05 | |

| 29 | Worthington-Smyth | Henri | 55 Jagbi Way, North Reading | 97676 | (855) 894-3758 | 2 | 2012-09-17 12:27:15 |

| 30 | Compétence | Millicent | 641 Drudgery Close, Burnington, Boston | 34232 | (855) 941-9786 | 2 | 2012-09-18 19:04:01 |

| 33 | Tupperware | Jacinthe | 33 Cheerful Plaza, Drake Road, Westford | 68666 | (822) 665-5327 | 2012-09-18 19:32:05 | |

| 35 | Chasse | John | 5 Bullington Lane, Boston | 54333 | (899) 720-6978 | 30 | 2012-09-19 11:32:45 |

| 36 | Crumpet | Erica | Crimson Road, North Reading | 75655 | (811) 732-4816 | 2 | 2012-09-22 08:36:38 |

Répondre:

delete from cd . members where memid = 37 ; This exercise is a small increment on our previous one. Instead of deleting all bookings, this time we want to be a bit more targeted, and delete a single member that has never made a booking. To do this, we simply have to add a WHERE clause to our command, specifying the member we want to delete. You can see the parallels with SELECT and UPDATE statements here.

There's one interesting wrinkle here. Try this command out, but substituting in member id 0 instead. This member has made many bookings, and you'll find that the delete fails with an error about a foreign key constraint violation. This is an important concept in relational databases, so let's explore a little further.

Foreign keys are a mechanism for defining relationships between columns of different tables. In our case we use them to specify that the memid column of the bookings table is related to the memid column of the members table. The relationship (or 'constraint') specifies that for a given booking, the member specified in the booking must exist in the members table. It's useful to have this guarantee enforced by the database: it means that code using the database can rely on the presence of the member. It's hard (even impossible) to enforce this at higher levels: concurrent operations can interfere and leave your database in a broken state.

PostgreSQL supports various different kinds of constraints that allow you to enforce structure upon your data. For more information on constraints, check out the PostgreSQL documentation on foreign keys

In our previous exercises, we deleted a specific member who had never made a booking. How can we make that more general, to delete all members who have never made a booking?

Expected results:

| memid | nom de famille | prénom | adresse | code postal | téléphone | recommendedby | joindate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | INVITÉ | INVITÉ | INVITÉ | 0 | (000) 000-0000 | 2012-07-01 00:00:00 | |

| 1 | Forgeron | Darren | 8 Bloomsbury Close, Boston | 4321 | 555-555-5555 | 2012-07-02 12:02:05 | |

| 2 | Forgeron | Tracy | 8 Bloomsbury Close, New York | 4321 | 555-555-5555 | 2012-07-02 12:08:23 | |

| 3 | Rownam | Tim | 23 Highway Way, Boston | 23423 | (844) 693-0723 | 2012-07-03 09:32:15 | |

| 4 | Joplette | Janice | 20 Crossing Road, New York | 234 | (833) 942-4710 | 1 | 2012-07-03 10:25:05 |

| 5 | Butters | Gerald | 1065 Huntingdon Avenue, Boston | 56754 | (844) 078-4130 | 1 | 2012-07-09 10:44:09 |

| 6 | Tracy | Burton | 3 Tunisia Drive, Boston | 45678 | (822) 354-9973 | 2012-07-15 08:52:55 | |

| 7 | Oser | Nancy | 6 Hunting Lodge Way, Boston | 10383 | (833) 776-4001 | 4 | 2012-07-25 08:59:12 |

| 8 | Boothe | Tim | 3 Bloomsbury Close, Reading, 00234 | 234 | (811) 433-2547 | 3 | 2012-07-25 16:02:35 |

| 9 | Stibbons | Réfléchir | 5 Dragons Way, Winchester | 87630 | (833) 160-3900 | 6 | 2012-07-25 17:09:05 |

| 10 | Owen | Charles | 52 Cheshire Grove, Winchester, 28563 | 28563 | (855) 542-5251 | 1 | 2012-08-03 19:42:37 |

| 11 | Jones | David | 976 Gnats Close, Reading | 33862 | (844) 536-8036 | 4 | 2012-08-06 16:32:55 |

| 12 | Boulanger | Anne | 55 Powdery Street, Boston | 80743 | 844-076-5141 | 9 | 2012-08-10 14:23:22 |

| 13 | Farrell | Jemima | 103 Firth Avenue, North Reading | 57392 | (855) 016-0163 | 2012-08-10 14:28:01 | |

| 14 | Forgeron | Jack | 252 Binkington Way, Boston | 69302 | (822) 163-3254 | 1 | 2012-08-10 16:22:05 |

| 15 | Badre | Florence | 264 Ursula Drive, Westford | 84923 | (833) 499-3527 | 9 | 2012-08-10 17:52:03 |

| 16 | Boulanger | Timothée | 329 James Street, Reading | 58393 | 833-941-0824 | 13 | 2012-08-15 10:34:25 |

| 17 | Pinker | David | 5 Impreza Road, Boston | 65332 | 811 409-6734 | 13 | 2012-08-16 11:32:47 |

| 20 | Genting | Matthieu | 4 Nunnington Place, Wingfield, Boston | 52365 | (811) 972-1377 | 5 | 2012-08-19 14:55:55 |

| 21 | Mackenzie | Anna | 64 Perkington Lane, Reading | 64577 | (822) 661-2898 | 1 | 2012-08-26 09:32:05 |

| 22 | Coplin | Joan | 85 Bard Street, Bloomington, Boston | 43533 | (822) 499-2232 | 16 | 2012-08-29 08:32:41 |

| 24 | Sarwin | Ramnaresh | 12 Bullington Lane, Boston | 65464 | (822) 413-1470 | 15 | 2012-09-01 08:44:42 |

| 26 | Jones | Douglas | 976 Gnats Close, Reading | 11986 | 844 536-8036 | 11 | 2012-09-02 18:43:05 |

| 27 | Rumney | Henrietta | 3 Burkington Plaza, Boston | 78533 | (822) 989-8876 | 20 | 2012-09-05 08:42:35 |

| 28 | Farrell | David | 437 Granite Farm Road, Westford | 43532 | (855) 755-9876 | 2012-09-15 08:22:05 | |

| 29 | Worthington-Smyth | Henri | 55 Jagbi Way, North Reading | 97676 | (855) 894-3758 | 2 | 2012-09-17 12:27:15 |

| 30 | Compétence | Millicent | 641 Drudgery Close, Burnington, Boston | 34232 | (855) 941-9786 | 2 | 2012-09-18 19:04:01 |

| 33 | Tupperware | Jacinthe | 33 Cheerful Plaza, Drake Road, Westford | 68666 | (822) 665-5327 | 2012-09-18 19:32:05 | |

| 35 | Chasse | John | 5 Bullington Lane, Boston | 54333 | (899) 720-6978 | 30 | 2012-09-19 11:32:45 |

| 36 | Crumpet | Erica | Crimson Road, North Reading | 75655 | (811) 732-4816 | 2 | 2012-09-22 08:36:38 |

Répondre:

delete from cd . members where memid not in ( select memid from cd . bookings ); We can use subqueries to determine whether a row should be deleted or not. There's a couple of standard ways to do this. In our featured answer, the subquery produces a list of all the different member ids in the cd.bookings table. If a row in the table isn't in the list generated by the subquery, it gets deleted.

An alternative is to use a correlated subquery . Where our previous example runs a large subquery once, the correlated approach instead specifies a smaller subqueryto run against every row.

delete from cd . members mems where not exists ( select 1 from cd . bookings where memid = mems . memid );The two different forms can have different performance characteristics. Under the hood, your database engine is free to transform your query to execute it in a correlated or uncorrelated fashion, though, so things can be a little hard to predict.

Aggregation is one of those capabilities that really make you appreciate the power of relational database systems. It allows you to move beyond merely persisting your data, into the realm of asking truly interesting questions that can be used to inform decision making. This category covers aggregation at length, making use of standard grouping as well as more recent window functions.

If you struggle with these questions, I strongly recommend Learning SQL, by Alan Beaulieu and SQL Cookbook by Anthony Molinaro. In fact, get the latter anyway - it'll take you beyond anything you find on this site, and on multiple different database systems to boot.

For our first foray into aggregates, we're going to stick to something simple. We want to know how many facilities exist - simply produce a total count.

Expected results:

| compter |

|---|

| 9 |

Répondre:

select count ( * ) from cd . facilities ; Aggregation starts out pretty simply! The SQL above selects everything from our facilities table, and then counts the number of rows in the result set. The count function has a variety of uses:

COUNT(*) simply returns the number of rowsCOUNT(address) counts the number of non-null addresses in the result set.COUNT(DISTINCT address) counts the number of different addresses in the facilities table. The basic idea of an aggregate function is that it takes in a column of data, performs some function upon it, and outputs a scalar (single) value. There are a bunch more aggregation functions, including MAX , MIN , SUM , and AVG . These all do pretty much what you'd expect from their names :-).

One aspect of aggregate functions that people often find confusing is in queries like the below:

select facid, count ( * ) from cd . facilitiesTry it out, and you'll find that it doesn't work. This is because count(*) wants to collapse the facilities table into a single value - unfortunately, it can't do that, because there's a lot of different facids in cd.facilities - Postgres doesn't know which facid to pair the count with.

Instead, if you wanted a query that returns all the facids along with a count on each row, you can break the aggregation out into a subquery as below:

select facid,

( select count ( * ) from cd . facilities )

from cd . facilitiesWhen we have a subquery that returns a scalar value like this, Postgres knows to simply repeat the value for every row in cd.facilities.

Produce a count of the number of facilities that have a cost to guests of 10 or more.

| compter |

|---|

| 6 |

Répondre:

select count ( * ) from cd . facilities where guestcost >= 10 ; This one is only a simple modification to the previous question: we need to weed out the inexpensive facilities. This is easy to do using a WHERE clause. Our aggregation can now only see the expensive facilities.

Produce a count of the number of recommendations each member has made. Order by member ID.

Expected results:

| recommendedby | compter |

|---|---|

| 1 | 5 |

| 2 | 3 |

| 3 | 1 |

| 4 | 2 |

| 5 | 1 |

| 6 | 1 |

| 9 | 2 |

| 11 | 1 |

| 13 | 2 |

| 15 | 1 |

| 16 | 1 |

| 20 | 1 |

| 30 | 1 |

Répondre:

select recommendedby, count ( * )

from cd . members

where recommendedby is not null

group by recommendedby

order by recommendedby; Previously, we've seen that aggregation functions are applied to a column of values, and convert them into an aggregated scalar value. This is useful, but we often find that we don't want just a single aggregated result: for example, instead of knowing the total amount of money the club has made this month, I might want to know how much money each different facility has made, or which times of day were most lucrative.

In order to support this kind of behaviour, SQL has the GROUP BY construct. What this does is batch the data together into groups, and run the aggregation function separately for each group. When you specify a GROUP BY , the database produces an aggregated value for each distinct value in the supplied columns. In this case, we're saying 'for each distinct value of recommendedby, get me the number of times that value appears'.

Produce a list of the total number of slots booked per facility. For now, just produce an output table consisting of facility id and slots, sorted by facility id.

Expected results:

| facid | Total Slots |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1320 |

| 1 | 1278 |

| 2 | 1209 |

| 3 | 830 |

| 4 | 1404 |

| 5 | 228 |

| 6 | 1104 |

| 7 | 908 |

| 8 | 911 |

Répondre:

select facid, sum (slots) as " Total Slots "

from cd . bookings

group by facid

order by facid; Other than the fact that we've introduced the SUM aggregate function, there's not a great deal to say about this exercise. For each distinct facility id, the SUM function adds together everything in the slots column.

Produce a list of the total number of slots booked per facility in the month of September 2012. Produce an output table consisting of facility id and slots, sorted by the number of slots.

Expected results:

| facid | Total Slots |

|---|---|

| 5 | 122 |

| 3 | 422 |

| 7 | 426 |

| 8 | 471 |

| 6 | 540 |

| 2 | 570 |

| 1 | 588 |

| 0 | 591 |

| 4 | 648 |

Répondre:

select facid, sum (slots) as " Total Slots "

from cd . bookings

where

starttime >= ' 2012-09-01 '

and starttime < ' 2012-10-01 '

group by facid

order by sum (slots); This is only a minor alteration of our previous example. Remember that aggregation happens after the WHERE clause is evaluated: we thus use the WHERE to restrict the data we aggregate over, and our aggregation only sees data from a single month.

Produce a list of the total number of slots booked per facility per month in the year of 2012. Produce an output table consisting of facility id and slots, sorted by the id and month.

Expected results:

| facid | mois | Total Slots |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 7 | 270 |

| 0 | 8 | 459 |

| 0 | 9 | 591 |

| 1 | 7 | 207 |

| 1 | 8 | 483 |

| 1 | 9 | 588 |

| 2 | 7 | 180 |

| 2 | 8 | 459 |

| 2 | 9 | 570 |

| 3 | 7 | 104 |

| 3 | 8 | 304 |

| 3 | 9 | 422 |

| 4 | 7 | 264 |

| 4 | 8 | 492 |

| 4 | 9 | 648 |

| 5 | 7 | 24 |

| 5 | 8 | 82 |

| 5 | 9 | 122 |

| 6 | 7 | 164 |

| 6 | 8 | 400 |

| 6 | 9 | 540 |

| 7 | 7 | 156 |

| 7 | 8 | 326 |

| 7 | 9 | 426 |

| 8 | 7 | 117 |

| 8 | 8 | 322 |

| 8 | 9 | 471 |

Répondre:

select facid, extract(month from starttime) as month, sum (slots) as " Total Slots "

from cd . bookings

where

starttime >= ' 2012-01-01 '

and starttime < ' 2013-01-01 '

group by facid, month

order by facid, month; The main piece of new functionality in this question is the EXTRACT function. EXTRACT allows you to get individual components of a timestamp, like day, month, year, etc. We group by the output of this function to provide per-month values. An alternative, if we needed to distinguish between the same month in different years, is to make use of the DATE_TRUNC function, which truncates a date to a given granularity.

It's also worth noting that this is the first time we've truly made use of the ability to group by more than one column.

Find the total number of members who have made at least one booking.

Expected results:

| compter |

|---|

| 30 |

Répondre:

select count (distinct memid) from cd . bookings Your first instinct may be to go for a subquery here. Something like the below:

select count ( * ) from

( select distinct memid from cd . bookings ) as mems This does work perfectly well, but we can simplify a touch with the help of a little extra knowledge in the form of COUNT DISTINCT . This does what you might expect, counting the distinct values in the passed column.

Produce a list of facilities with more than 1000 slots booked. Produce an output table consisting of facility id and hours, sorted by facility id.

Expected results:

| facid | Total Slots |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1320 |

| 1 | 1278 |

| 2 | 1209 |

| 4 | 1404 |

| 6 | 1104 |

Répondre:

select facid, sum (slots) as " Total Slots "

from cd . bookings

group by facid

having sum (slots) > 1000

order by facid It turns out that there's actually an SQL keyword designed to help with the filtering of output from aggregate functions. This keyword is HAVING .

The behaviour of HAVING is easily confused with that of WHERE . The best way to think about it is that in the context of a query with an aggregate function, WHERE is used to filter what data gets input into the aggregate function, while HAVING is used to filter the data once it is output from the function. Try experimenting to explore this difference!

Produce a list of facilities along with their total revenue. The output table should consist of facility name and revenue, sorted by revenue. Remember that there's a different cost for guests and members!

Expected results:

| nom | revenu |

|---|---|

| Tennis de table | 180 |

| Snooker Table | 240 |

| Table de billard | 270 |

| Badminton Court | 1906.5 |

| Squash Court | 13468.0 |

| Tennis Court 1 | 13860 |

| Tennis Court 2 | 14310 |

| Massage Room 2 | 15810 |

| Massage Room 1 | 72540 |

Répondre:

select facs . name , sum (slots * case

when memid = 0 then facs . guestcost

else facs . membercost

end) as revenue

from cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

group by facs . name

order by revenue; The only real complexity in this query is that guests (member ID 0) have a different cost to everyone else. We use a case statement to produce the cost for each session, and then sum each of those sessions, grouped by facility.

Produce a list of facilities with a total revenue less than 1000. Produce an output table consisting of facility name and revenue, sorted by revenue. Remember that there's a different cost for guests and members!

Expected results:

| nom | revenu |

|---|---|

| Tennis de table | 180 |

| Snooker Table | 240 |

| Table de billard | 270 |

Répondre:

select name, revenue from (

select facs . name , sum (case

when memid = 0 then slots * facs . guestcost

else slots * membercost

end) as revenue

from cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

group by facs . name

) as agg where revenue < 1000

order by revenue; You may well have tried to use the HAVING keyword we introduced in an earlier exercise, producing something like below:

select facs . name , sum (case

when memid = 0 then slots * facs . guestcost

else slots * membercost

end) as revenue

from cd . bookings bks

inner join cd . facilities facs

on bks . facid = facs . facid

group by facs . name

having revenue < 1000

order by revenue; Unfortunately, this doesn't work! You'll get an error along the lines of ERROR: column "revenue" does not exist . Postgres, unlike some other RDBMSs like SQL Server and MySQL, doesn't support putting column names in the HAVING clause. This means that for this query to work, you'd have to produce something like below:

select facs . name , sum (case