Kobweb est un framework Kotlin d'opinion pour la création de sites Web et d'applications Web, construits au-dessus de composer HTML et inspiré par Next.js et Chakra UI.

@Page

@Composable

fun HomePage () {

Column ( Modifier .fillMaxWidth(), horizontalAlignment = Alignment . CenterHorizontally ) {

Row ( Modifier .align( Alignment . End )) {

var colorMode by ColorMode .currentState

Button (

onClick = { colorMode = colorMode.opposite },

Modifier .borderRadius( 50 .percent).padding( 0 .px)

) {

// Includes support for Font Awesome icons

if (colorMode.isLight) FaSun () else FaMoon ()

}

}

H1 {

Text ( " Welcome to Kobweb! " )

}

Row ( Modifier .flexWrap( FlexWrap . Wrap )) {

SpanText ( " Create rich, dynamic web apps with ease, leveraging " )

Link ( " https://kotlinlang.org/ " , " Kotlin " )

SpanText ( " and " )

Link ( " https://github.com/JetBrains/compose-multiplatform#compose-html/ " , " Compose HTML " )

}

}

}

Bien que Kobweb soit encore avant 1,0, il est utilisable depuis un certain temps maintenant. Il fournit des trappes d'échappement aux API de niveau inférieur, vous pouvez donc accomplir quoi que ce soit même si Kobweb ne le soutient pas encore. Veuillez envisager de mettre en vedette le projet pour indiquer l'intérêt, nous savons donc que nous créons quelque chose que la communauté veut. À quel point est-il prêt? ▼

Notre objectif est de fournir:

Voici une démo où nous créons un projet HTML composé à partir de zéro avec le support Markdown et le rechargement en direct, en moins de 10 secondes:

Vous pouvez consulter mon discours sur DroidCon SF 24 pour un aperçu de haut niveau de Kobweb. Le discours présente ce que Kobweb peut faire, introduit composer HTML (qu'il construit sur) et couvre une large gamme de fonctionnalités frontales et backend. Il est léger sur le code mais lourd sur la compréhension de la structure et des capacités du cadre.

L'un des utilisateurs de Kobweb, Stevdza-san, a créé des tutoriels de démarrage gratuits qui montrent comment créer des projets à l'aide de Kobweb.

Conseil

Il est facile de commencer avec un site de mise en page statique d'abord et de migrer vers un site de pile complet plus tard. (Vous pouvez en savoir plus sur la mise en page statique par rapport aux sites de pile complète ▼ ci-dessous.)

Une chaîne YouTube appelée Skyfish a créé une vidéo de tutoriel sur la façon de construire un site Fullstack avec Kobweb.

La première étape consiste à obtenir le binaire Kobweb. Vous pouvez l'installer, le télécharger et / ou le construire, nous inclurons donc des instructions pour toutes ces approches.

Un grand merci à Aalmiray et Helpermethod pour m'aider à faire fonctionner ces options d'installation. Consultez Jreleaser si vous avez besoin de le faire dans votre propre projet!

OS: Mac et Linux

$ brew install varabyte/tap/kobwebOS: Windows

# Note: Adding buckets only has to be done once.

# Feel free to skip java if you already have it

> scoop bucket add java

> scoop install java/openjdk

# Install kobweb

> scoop bucket add varabyte https://github.com/varabyte/scoop-varabyte.git

> scoop install varabyte/kobwebOS: Windows, Mac et * Nix

$ sdk install kobwebMerci une tonne à AKSH1618 pour avoir ajouté un support pour cette cible!

Avec une aide AUR, par exemple:

$ yay -S kobweb

$ paru -S kobweb

$ trizen -S kobweb

# etc.Sans aide AUR:

$ git clone https://aur.archlinux.org/kobweb.git

$ cd kobweb

$ makepkg -siVeuillez voir: Varabyte / Kobweb-Cli # 11 et envisagez de laisser un commentaire!

Notre artefact binaire est hébergé sur Github. Pour télécharger les derniers, vous pouvez soit saisir le fichier Zip ou Tar à partir de GitHub, soit le récupérer à partir de votre terminal:

$ cd /path/to/applications

# You can either pull down the zip file

$ wget https://github.com/varabyte/kobweb-cli/releases/download/v0.9.18/kobweb-0.9.18.zip

$ unzip kobweb-0.9.18.zip

# ... or the tar file

$ wget https://github.com/varabyte/kobweb-cli/releases/download/v0.9.18/kobweb-0.9.18.tar

$ tar -xvf kobweb-0.9.18.tarEt je recommande de l'ajouter à votre chemin, soit directement:

$ PATH= $PATH :/path/to/applications/kobweb-0.9.18/bin

$ kobweb version # to check it's workingou via un lien symbolique:

$ cd /path/to/bin # some folder you've created that's in your PATH

$ ln -s /path/to/applications/kobweb-0.9.18/bin/kobweb kobwebBien que nous hébergeons des artefacts Kobweb sur GitHub, il est assez facile de construire le vôtre.

La construction de Kobweb nécessite JDK11 ou plus récente. Nous allons d'abord discuter de la façon de l'ajouter.

Si vous voulez un contrôle complet sur votre installation JDK, le téléchargement manuellement est une bonne option.

JAVA_HOME pour le pointer. JAVA_HOME=/path/to/jdks/corretto-11.0.12

# ... or whatever version or path you chosePour une approche plus automatisée, vous pouvez demander à IntelliJ d'installer un JDK pour vous.

Suivez leurs instructions ici: https://www.jetbrains.com/help/idea/sdk.html#set-up-jdk

La CLI de Kobweb est en fait maintenue dans un dépôt de github séparé. Une fois que vous avez la configuration du JDK, il devrait être facile de le cloner et de le construire:

$ cd /path/to/src/root # some folder you've created for storing src code

$ git clone https://github.com/varabyte/kobweb-cli

$ cd kobweb-cli

$ ./gradlew :kobweb:installDistEnfin, mettez à jour votre chemin:

$ PATH= $PATH :/path/to/src/root/kobweb-cli/kobweb/build/install/kobweb/bin

$ kobweb version # to check it's working Si vous avez précédemment installé KOBWEB et que vous savez qu'une nouvelle version est disponible, la façon dont vous le mettez à jour dépend de la façon dont vous l'avez installé.

| Méthode | Instructions |

|---|---|

| Homebrew | brew updatebrew upgrade kobweb |

| Scoop | scoop update kobweb |

| Sdkman! | sdk upgrade kobweb |

| Arch Linux | Les étapes d'installation de rediffusion devraient fonctionner. Si vous utilisez une aide AUR, vous devrez peut-être revoir son manuel. |

| Téléchargé à partir de Github | Visitez la dernière version. Vous pouvez y trouver un fichier ZIP et TAR. |

$ cd /path/to/projects/

$ kobweb create appOn vous pose quelques questions nécessaires pour mettre en place votre projet.

Vous n'avez pas besoin de créer un dossier racine pour votre projet à l'avance - le processus de configuration vous invitera à créer. Pour les parties restantes de cette section, disons que vous choisissez le dossier "my-project" lorsqu'on lui a demandé.

Une fois terminé, vous aurez un projet de base avec deux pages - une page d'accueil et une page à propos (avec la page à propos écrite dans Markdown) - et certains composants (qui sont des collections de pièces composables réutilisables). Votre propre structure de répertoire devrait ressembler à ceci:

my-project

└── site/src/jsMain

├── kotlin.org.example.myproject

│ ├── components

│ │ ├── layouts

│ │ │ ├── MarkdownLayout.kt

│ │ │ └── PageLayout.kt

│ │ ├── sections

│ │ │ ├── Footer.kt

│ │ │ └── NavHeader.kt

│ │ └── widgets

│ │ └── IconButton.kt

│ ├── pages

│ │ └── Index.kt

│ └── AppEntry.kt

└── resources/markdown

└── About.md

Notez qu'il n'y a pas d'index.html ou de logique de routage nulle part! Nous générons cela pour vous automatiquement lorsque vous exécutez Kobweb. Cela nous amène à la section suivante ...

$ cd your-project/site

$ kobweb run Cette commande fait tourner un serveur Web sur http: // localhost: 8080. Si vous souhaitez configurer le port, vous pouvez le faire en modifiant le fichier .kobweb/conf.yaml de votre projet.

Vous pouvez ouvrir votre projet dans Intellij et commencer à le modifier. Pendant que Kobweb s'exécute, il détectera les modifications, recompilera et déploiera automatiquement les mises à jour de votre site.

Si vous ne souhaitez pas garder une fenêtre de terminal séparée ouverte à côté de votre fenêtre IDE, vous pouvez préférer des solutions alternatives.

Vous pouvez utiliser la fenêtre d'outil Terminal IntelliJ pour y exécuter kobweb . Si vous rencontrez une erreur de compilation, les lignes de trace de pile seront décorées avec des liens, ce qui facilite la navigation vers la source pertinente.

kobweb lui-même délégue à Gradle, mais rien ne vous empêche d'appeler les commandes vous-même. Vous pouvez créer des configurations Gradle Run pour chacune des commandes KOBWEB.

Conseil

Lorsque vous exécutez une commande Kobweb CLI qui délègue à Gradle, il enregistrera la commande Gradle à la console. C'est ainsi que vous pouvez découvrir les commandes Gradle discutées dans cette section.

kobwebStart -t .-t (ou, --continuous ) indique à Gradle de surveiller les modifications de fichiers, ce qui vous donne un comportement de chargement en direct.kobwebStop .kobwebExport -PkobwebReuseServer=false -PkobwebEnv=DEV -PkobwebRunLayout=FULLSTACK -PkobwebBuildTarget=RELEASE -PkobwebExportLayout=FULLSTACK-PkobwebExportLayout=STATIC .kobwebStart -PkobwebEnv=PROD -PkobwebRunLayout=FULLSTACK-PkobwebRunLayout=STATIC .Vous pouvez tout lire sur l'intégration de Gradle d'Intellij ici. Ou pour simplement sauter directement dans la façon de créer des configurations d'exécution pour l'une des commandes discutées ci-dessus, lisez ces instructions.

Kobweb vous fournira une collection croissante d'échantillons pour que vous puissiez apprendre. Pour voir ce qui est disponible, courez:

$ kobweb list

You can create the following Kobweb projects by typing ` kobweb create ... `

• app: A template for a minimal site that demonstrates the basic features of Kobweb

• examples/jb/counter: A very minimal site with just a counter (based on the Jetbrains tutorial)

• examples/todo: An example TODO app, showcasing client / server interactions Par exemple, kobweb create examples/todo instanciera une application TODO localement.

Les modèles de projet créés par Kobweb embrassent tous les catalogues de version Gradle.

Si vous n'êtes pas au courant, c'est un fichier qui existe sur gradle/libs.versions.toml . Si vous vous retrouvez à vouloir modifier ou ajouter de nouvelles versions aux projets que vous avez créés à l'origine via kobweb create , c'est là que vous les trouverez.

Par exemple, voici les libs.versions.toml que nous utilisons pour notre propre site d'atterrissage.

Pour en savoir plus sur la fonctionnalité, veuillez consulter les documents officiels.

La dernière version disponible de Kobweb est déclarée en haut de cette lecture. Si une nouvelle version est sortie, vous pouvez mettre à jour votre propre projet en modifiant gradle/libs.version.toml et en mettant à jour la version kobweb là-bas.

Important

Vous devez revérifier la compatibilité.md pour voir si vous devez également mettre à jour vos versions kotlin et jetbrains-compose .

Prudence

Cela peut être déroutant, mais Kobweb a deux versions - la version pour la bibliothèque elle-même (celle qui est applicable dans cette situation), et celle de l'outil de ligne de commande.

Kobweb, à la base, est une poignée de classes responsables de la réduction d'une grande partie de la passerelle autour de la construction d'une application HTML Compose, telles que le routage et la configuration des styles CSS de base. Kobweb fournit en outre un plugin Gradle qui analyse votre base de code et génère du code de chauffeur pertinent.

Kobweb est également un binaire CLI du même nom qui fournit des commandes pour gérer les parties fastidieuses du bâtiment et / ou exécuter une application HTML Compose. Nous voulons éloigner ces trucs, vous pouvez donc profiter de vous concentrer sur le travail plus intéressant!

(Pour en savoir plus sur Compose HTML, veuillez visiter les tutoriels officiels).

Créer une page est facile! C'est juste une méthode @Composable normale. Pour mettre à niveau votre composable sur une page, tout ce que vous avez à faire est:

pages dans votre répertoire source jsMain .@PageJuste à partir de cela, Kobweb créera automatiquement une entrée de site.

Par exemple, si je crée le fichier suivant:

// jsMain/kotlin/com/mysite/pages/admin/Settings.kt

@Page

@Composable

fun SettingsPage () {

/* ... */

} Cela créera une page que je peux ensuite visiter en allant sur mysite.com/admin/settings .

Important

La dernière partie d'une URL, ici, settings , s'appelle une limace .

Par défaut, le limace provient du nom de fichier, qui est converti en cas de kebab, par exemple à AboutUs.kt se transformer en about-us . Cependant, cela peut être remplacé par ce que vous voulez (plus à ce sujet sous peu).

Le nom de fichier Index.kt est spécial. Si une page est définie dans un tel fichier, il sera traité comme la page par défaut sous cette URL. Par exemple, une page définie dans .../pages/admin/Index.kt sera visitée si l'utilisateur visite mysite.com/admin/ .

Si vous avez besoin de modifier l'itinéraire généré pour une page, vous pouvez définir le champ routeOverride de l'annotation Page :

// jsMain/kotlin/com/mysite/pages/admin/Settings.kt

@Page(routeOverride = " config " )

@Composable

fun SettingsPage () {

/* ... */

} Ce qui précède créerait une page que vous pourriez visiter en allant sur mysite.com/admin/config .

routeOverride peut en outre contenir des barres obliques, et si la valeur commence et / ou se termine par une barre oblique, cela a une signification particulière.

Et si vous définissez le remplacement sur "index", cela se comporte la même chose que la définition du fichier sur Index.kt comme décrit ci-dessus.

Certains exemples peuvent clarifier ces règles (et comment elles se comportent lorsqu'elles sont combinées). En supposant que nous définissons une page pour notre site example.com dans le fichier a/b/c/Slug.kt :

| Annotation | URL résultant |

|---|---|

@Page | example.com/a/b/c/slug |

@Page("other") | example.com/a/b/c/other |

@Page("index") | example.com/a/b/c/ |

@Page("d/e/f/") | example.com/a/b/c/d/e/f/slug |

@Page("d/e/f/other") | example.com/a/b/c/d/e/f/other |

@Page("d/e/f/index") | example.com/a/b/c/d/e/f/ |

@Page("/d/e/f/") | example.com/d/e/f/slug |

@Page("/d/e/f/other") | example.com/d/e/f/other |

@Page("/d/e/f/index") | example.com/d/e/f/ |

@Page("/") | example.com/slug |

@Page("/other") | example.com/other |

@Page("/index") | example.com/ |

Prudence

Malgré la flexibilité autorisée ici, vous ne devriez pas utiliser cette fonctionnalité fréquemment, voire pas du tout. Un projet Kobweb profite du fait qu'un utilisateur peut facilement associer une URL sur votre site à un fichier dans votre base de code, mais cette fonctionnalité vous permet de rompre ces hypothèses. Il est principalement fourni pour activer le routage dynamique (voir la section Routes dynamiques ▼) ou activer un nom d'URL qui utilise des caractères qui ne sont pas autorisés dans les noms de fichiers Kotlin.

Alors que la limace est dérivée du nom de fichier, les parties antérieures de l'itinéraire sont dérivées du package du fichier.

Un package sera converti en une partie d'itinéraire en supprimant les soulignements de premier plan ou de fin (car ceux-ci sont souvent utilisés pour contourner les limitations en ce qui concerne les valeurs et les mots clés dans un /team/our-values/ de package, par site.pages.team.ourValues site.events.fun_ site.pages.blog._2022 .

Si vous souhaitez remplacer la pièce d'itinéraire générée pour un package, vous pouvez utiliser l'annotation PackageMapping .

Par exemple, disons que votre équipe préfère ne pas utiliser de packages de chameaux pour des raisons esthétiques. Ou peut-être que vous souhaitez intentionnellement ajouter un soulignement principal dans la partie de l'itinéraire de votre site pour un certain accent (car plus tôt, nous avons mentionné que les soulignements de premier plan sont supprimés automatiquement), comme dans l'itinéraire /team/_internal/contact-numbers . Vous pouvez utiliser des mappages de packages pour cela.

Vous appliquez l'annotation de mappage de package au fichier actuel. L'utiliser ressemble à ceci:

// site/pages/team/values/PackageMapping.kt

@file:PackageMapping( " our-values " )

package site.pages.blog.values

import com.varabyte.kobweb.core.PackageMapping Avec la cartographie des packages ci-dessus en place, un fichier qui vit sur site/pages/team/values/Mission.kt sera visité à /team/our-values/mission .

Chaque méthode de page donne accès à sa PageContext via la méthode rememberPageContext() .

Surtout, le contexte d'une page lui donne accès à un routeur, vous permettant de naviguer vers d'autres pages.

Il fournit également des informations dynamiques sur l'URL de la page actuelle (discutée dans la section suivante).

@Page

@Composable

fun ExamplePage () {

val ctx = rememberPageContext()

Button (onClick = { ctx.router.navigateTo( " /other/page " ) }) {

Text ( " Click me " )

}

}Vous pouvez utiliser le contexte de la page pour vérifier les valeurs de tous les paramètres de requête transmis dans l'URL de la page actuelle.

Donc, si vous visitez site.com/posts?id=12345&mode=edit , vous pouvez interroger ces valeurs comme ainsi:

enum class Mode {

EDIT , VIEW ;

companion object {

fun from ( value : String ) {

entries.find { it.name.equals(value, ignoreCase = true ) }

? : error( " Unknown mode: $value " )

}

}

}

@Page

@Composable

fun Posts () {

val ctx = rememberPageContext()

// Here, I'm assuming these params are always present, but you can use

// `get` instead of `getValue` to handle the nullable case. Care should

// also be taken to parse invalid values without throwing an exception.

val postId = ctx.route.params.getValue( " id " ).toInt()

val mode = Mode .from(ctx.route.params.getValue( " mode " ))

/* ... */

} En plus des paramètres de requête, Kobweb prend en charge les arguments d'intégration directement dans l'URL elle-même. Par exemple, vous souhaiterez peut-être enregistrer le chemin users/{user}/posts/{post} qui serait visité si le visiteur du site tapait une URL comme users/bitspittle/posts/20211231103156 .

Comment le configurer? Heureusement, c'est assez facile.

Mais tout d'abord, notez que dans l'exemple users/{user}/posts/{post} il y a en fait deux pièces dynamiques différentes, une au milieu et une à l'extrémité de la queue. Ceux-ci peuvent être gérés par le PackageMapping et les annotations Page , respectivement.

Faites attention à l'utilisation des accolades bouclées dans le nom de cartographie! Cela permet à Kobweb de savoir qu'il s'agit d'un package dynamique.

// pages/users/user/PackageMapping.kt

@file:PackageMapping( " {user} " ) // or @file:PackageMapping("{}")

package site.pages.users.user

import com.varabyte.kobweb.core.PackageMapping Si vous passez un "{}" vide dans l'annotation PackageMapping , il ordonne à Kobweb d'utiliser le nom du package lui-même (c'est-à-dire user dans ce cas spécifique).

Comme PackageMapping , l'annotation Page peut également prendre des accolades bouclées pour indiquer une valeur dynamique.

// pages/users/user/posts/Post.kt

@Page( " {post} " ) // Or @Page("{}")

@Composable

fun PostPage () {

/* ... */

} Un "{}" vide dit à Kobweb d'utiliser le nom du fichier actuel.

N'oubliez pas que l'annotation Page vous permet de réécrire toute la route. Cette valeur accepte également des pièces dynamiques, vous pouvez donc même faire quelque chose comme:

// pages/users/user/posts/Post.kt

@Page( " /users/{user}/posts/{post} " ) // Or @Page("/users/{user}/posts/{}")

@Composable

fun PostPage () {

/* ... */

}Mais avec une grande puissance vient une grande responsabilité. Des astuces comme celle-ci peuvent être difficiles à trouver et / ou à mettre à jour plus tard, d'autant plus que votre projet augmente. Bien que cela fonctionne, vous ne devez utiliser ce format que dans des cas où vous en avez absolument besoin (peut-être après un refactor de code où vous devez prendre en charge les chemins d'url hérités).

Vous interrogez les valeurs de route dynamique exactement de la même manière que si vous demandiez des paramètres de requête. C'est-à-dire utiliser ctx.params :

@Page( " {} " )

@Composable

fun PostPage () {

val ctx = rememberPageContext()

val postId = ctx.route.params.getValue( " post " )

/* ... */

}Important

Vous devez éviter de créer des chemins URL où le chemin dynamique et les paramètres de requête ont le même nom, que dans mysite.com/posts/{post}?post=... S'il y a un conflit, les paramètres de route dynamique auront la priorité. (Vous pouvez toujours accéder à la valeur du paramètre de requête via ctx.route.queryParams dans ce cas si nécessaire.)

Si vous avez une ressource que vous souhaitez servir à partir de votre site, vous gérez cela en la plaçant dans le dossier jsMain/resources/public de votre site.

Par exemple, si vous avez un logo, vous souhaitez être disponible sur mysite.com/assets/images/logo.png , vous le metriez dans votre projet Kobweb sur jsMain/resources/public/assets/images/logo.png .

En d'autres termes, tout ce qui est dans le cadre de votre répertoire de votre projet Resources public/ Resources sera automatiquement copié sur votre site final (sans compter le public/ la partie).

Pour ceux qui sont nouveaux sur Web Dev, il convient de comprendre qu'il existe deux façons de définir des styles sur vos éléments HTML: en ligne et en feuille de style.

Les styles en ligne sont définis sur la balise d'élément elle-même. Dans HTML brut, cela pourrait ressembler:

< div style =" background-color:black " >Pendant ce temps, toute page HTML donnée peut faire référence à une liste de feuilles de style qui peuvent définir un tas de styles, où chaque style est lié à un sélecteur (une règle qui sélectionne les éléments auxquels ces styles s'appliquent).

Un exemple concret d'une feuille de style très courte peut aider ici:

body {

background-color : black;

color : magenta

}

# title {

color : yellow

}Et vous pouvez utiliser cette feuille de style pour styliser le document suivant:

< body >

<!-- Title gets background-color from "body" and foreground color from "#title" -->

< div id =" title " > Yellow on black </ div >

Magenta on black

</ body > Note

Lorsque des styles contradictoires sont présents à la fois dans une feuille de style et en tant que déclaration en ligne, les styles en ligne ont priorité.

Il n'y a pas de règle stricte et rapide, mais en général, lors de l'écriture de HTML / CSS à la main, les feuilles de style sont souvent préférées aux styles en ligne car il maintient mieux une séparation des préoccupations. Autrement dit, le HTML devrait représenter le contenu de votre site, tandis que le CSS contrôle l'apparence et la sensation.

Cependant! Nous n'écrivons pas à la main HTML / CSS. Nous utilisons Compose HTML! Devrions-nous même nous soucier de cela à Kotlin?

En fait, il y a des moments où vous devez utiliser des feuilles de style, car sans eux, vous ne pouvez pas définir des styles pour les comportements avancés (en particulier les pseudo-classes, les pseudo-éléments et les requêtes multimédias). Par exemple, vous ne pouvez pas remplacer la couleur des liens visités sans utiliser une approche de feuille de style. Il vaut donc la peine de réaliser qu'il existe des différences fondamentales.

Enfin, il peut également être beaucoup plus facile de déboguer votre page avec des outils de navigateur lorsque vous vous appuyez sur des styles de styles sur les styles en ligne, car il rend votre Dom Tree plus facile à lire lorsque vos éléments sont simples (par exemple <div class="title"> vs. <div style="color:yellow; background-color:black; font-size: 24px; ..."> ).

Nous allons présenter et discuter des modificateurs et des blocs de style CSS plus en détail. Mais en général, lorsque vous passez des modificateurs directement dans un widget composable en soie, ceux-ci entraîneront des styles en ligne, tandis que si vous utilisez un bloc de style CSS pour définir vos styles, ceux-ci seront intégrés dans la feuille de style du site:

// Uses inline styles

Box ( Modifier .color( Colors . Red )) { /* ... */ }

// Uses a stylesheet

val BoxStyle = CssStyle {

base { Modifier . Color ( Colors . Red ) }

}

Box ( BoxStyle .toModifier()) { /* ... */ }En tant que débutant, ou même en tant qu'utilisateur avancé lors du prototypage, n'hésitez pas à utiliser les modificateurs en ligne autant que vous le pouvez, pivotant les blocs de style CSS si vous avez besoin d'utiliser des pseudo-classes, des pseudo-éléments ou des requêtes multimédias. Il est assez facile de migrer les styles en ligne vers des feuilles de style à Kobweb.

Dans mes propres projets, j'ai tendance à utiliser des styles en ligne pour des éléments de mise en page vraiment simples (par exemple Row(Modifier.fillMaxWidth()) ) et des blocs de style CSS pour des widgets complexes et / ou réutilisables. Il devient en fait une belle convention organisationnelle d'avoir tous vos styles regroupés en un seul endroit au-dessus du widget lui-même.

Kobweb présente la classe Modifier , afin de fournir une expérience similaire à ce que vous trouvez dans Jetpack Compose. (Vous pouvez en savoir plus à leur sujet ici si vous n'êtes pas familier avec le concept).

Dans le monde de Compose HTML, vous pouvez considérer un Modifier comme un emballage au-dessus des styles et des attributs CSS.

Important

Veuillez vous référer à la documentation officielle si vous n'êtes pas familier avec les attributs et / ou les styles HTML.

Alors ceci:

Modifier .backgroundColor( Colors . Red ).color( Colors . Green ).padding( 200 .px) Lorsqu'il est passé dans un widget fourni par Kobweb, comme Box :

Box ( Modifier .backgroundColor( Colors . Red ).color( Colors . Green ).padding( 200 .px)) {

/* ... */

} Générerait une balise HTML avec une propriété de style comme: <div style="background:red;color:green;padding:200px">

Il y a un tas d'extensions de modificateurs (et elles se développent) fournies par Kobweb, comme background , color et padding ci-dessus. Mais il y a aussi deux trappes d'évasion à chaque fois que vous rencontrez un modificateur qui manque: attrsModifier et styleModifier .

À ce stade, vous interagissez avec Compose HTML, une couche sous Kobweb.

Les utiliser ressemble à ceci:

// Modify attributes of an element tag

// e.g. the "a", "b", and "c" in <tag a="..." b="..." c="..." />

Modifier .attrsModifier {

id( " example " )

}

// Modify styles of an element tag

// e.g. the "x", "y", and "z" in `<tag a="..." b="..." c="..." style="x:...;y:...;z:..." />

Modifier .styleModifier {

width( 100 .percent)

height( 50 .percent)

}

// Note: Because "style" itself is an attribute, you can define styles in an attrsModifier:

Modifier .attrsModifier {

id( " example " )

style {

width( 100 .percent)

height( 50 .percent)

}

}

// ... but in the above case, you should use a styleModifier for simplicity Dans le cas occasionnel (et, espérons-le, rare!) Où Kobweb ne fournit pas de modificateur et compose HTML ne fournit pas l'attribut ou le support de style dont vous avez besoin, vous pouvez utiliser attrsModifier plus la méthode attr ou styleModifier plus la méthode property . Cette trappe d'évacuation dans une trappe d'évacuation vous permet de fournir toute valeur personnalisée dont vous avez besoin.

Les cas ci-dessus peuvent être réécrits comme:

Modifier .attrsModifier {

attr( " id " , " example " )

}

Modifier .styleModifier {

property( " width " , 100 .percent)

// Or even raw CSS:

// property("width", "100%")

property( " height " , 50 .percent)

} Enfin, notez que les styles sont, par la conception de CSS, applicables à n'importe quel élément, tandis que les attributs sont souvent liés à ceux spécifiques. Par exemple, l'attribut id peut être appliqué à n'importe quel élément, mais href ne peut être appliqué qu'à une balise a Étant donné que les modificateurs n'ont pas de contexte dans quel élément dans lequel ils sont transmis, Kobweb vise uniquement à fournir des modificateurs d'attribut pour les attributs globaux (par exemple Modifier.id("example") ) et pas d'autres.

Ainsi, l'utilisation attrsModifier (ou son Modifier.attr de raccourci.ATTR) dans votre propre code ainsi que Modifier.toAttrs (qui convertit un Modifier en un bloc d'attributs qui peut être transmis en widgets HTML Compose) pour définir des valeurs d'attribut est souvent acceptable.

Cependant, si vous finissez par utiliser styleModifier { property(key, value) } dans votre propre base de code, envisagez de déposer un problème avec nous afin que nous puissions ajouter le modificateur manquant à la bibliothèque. À tout le moins, vous êtes encouragé à définir votre propre méthode d'extension pour créer votre propre modificateur de style de type type.

La soie est une couche d'interface utilisateur incluse avec Kobweb et construite sur Compose HTML.

Alors que Compose HTML vous oblige à comprendre les concepts HTML / CSS sous-jacents, la soie tente de résumer une partie de celle-ci, en fournissant une API plus semblable à ce que vous pourriez vivre une application de composition sur Android ou Desktop. Moins "div, span, flexbox, attrs, styles, classes" et plus "lignes, colonnes, boîtes et modificateurs".

Nous considérons la soie comme une partie assez importante de l'expérience de Kobweb, mais il convient de souligner qu'il est conçu comme un composant facultatif. Vous pouvez absolument utiliser Kobweb sans soie. (Vous pouvez également utiliser la soie sans kobweb!).

Vous pouvez également entrelacer la soie et composer facilement les composants HTML (car la soie est simplement en les composant elle-même).

@InitSilk Avant d'aller plus loin, nous voulons mentionner rapidement que vous pouvez annoter une méthode avec @InitSilk , qui sera appelée lorsque votre site démarre.

Cette méthode doit prendre un seul paramètre InitSilkContext . Un contexte contient diverses propriétés qui permettent d'ajuster les paramètres de la soie, qui seront démontrées plus en détail dans les sections ci-dessous.

@InitSilk

fun initSilk ( ctx : InitSilkContext ) {

// `ctx` has a handful of properties which allow you to adjust Silk's default behavior.

}Conseil

Les noms de vos méthodes @InitSilk n'ont pas d'importance, tant qu'ils sont publics, prenez un seul paramètre InitSilkContext et ne collisez pas avec une autre méthode du même nom. Vous êtes encouragé à choisir un nom à des fins de lisibilité.

Vous pouvez définir autant de méthodes @InitSilk que vous le souhaitez, alors n'hésitez pas à les diviser en pièces pertinentes, clairement nommées, au lieu de déclarer une méthode monolithique, génériquement nommée fun initSilk(ctx) qui fait tout.

Avec la soie, vous pouvez définir un style comme ainsi, en utilisant la fonction CssStyle et le bloc base :

val CustomStyle = CssStyle {

base {

Modifier .background( Colors . Red )

}

} et convertissez-le en modificateur en utilisant CustomStyle.toModifier() . À ce stade, vous pouvez le transmettre dans n'importe quel composable qui prend un paramètre Modifier :

// Approach #1 (uses inline styles)

Box ( Modifier .backgroundColor( Colors . Red )) { /* ... */ }

// Approach #2 (uses stylesheets)

Box ( CustomStyle .toModifier()) { /* ... */ }Important

Lorsque vous déclarez un CssStyle , il doit être public. En effet, le code est généré dans un fichier main.kt par le plugin Kobweb Gradle, et ce code doit être en mesure d'accéder à votre style afin de l'enregistrer.

En général, c'est une bonne idée de considérer les styles comme mondiaux de toute façon, car techniquement, ils vivent tous dans une feuille de style appliquée à l'échelle mondiale, et vous devez vous assurer que le nom de style est unique dans toute votre application.

Vous pouvez techniquement faire un style privé si vous ajoutez un peu de passe-partout pour gérer vous-même l'inscription:

@Suppress( " PRIVATE_COMPONENT_STYLE " )

private val ExampleCustomStyle = CssStyle { /* ... */ }

// Or use a leading underscore to automatically suppress the warning

private val _ExampleOtherCustomStyle = CssStyle { /* ... */ }

@InitSilk

fun registerPrivateStyle ( ctx : InitSilkContext ) {

// Kobweb will not be able to detect the property name, so a name must be provided manually

ctx.theme.registerStyle( " example-custom " , ExampleCustomStyle )

ctx.theme.registerStyle( " example-other-custom " , _ExampleOtherCustomStyle )

}Cependant, vous êtes encouragé à garder vos styles publics et à laisser le plugin Kobweb Gradle gérer tout pour vous.

CssStyle.base Vous pouvez simplifier le syntaxe des blocs de style de base un peu plus loin avec la déclaration CssStyle.base :

val CustomStyle = CssStyle .base {

Modifier .background( Colors . Red )

}Sachez simplement que vous devrez peut-être éclater à nouveau si vous avez besoin de prendre en charge des sélecteurs supplémentaires ▼.

Le plugin Kobweb Gradle détecte automatiquement vos propriétés CssStyle et génère un nom pour vous, dérivé du nom de la propriété lui-même mais en utilisant un boîtier Kebab.

Par exemple, si vous écrivez val TitleTextStyle = CssStyle { ... } , son nom sera "Title-Text".

Vous n'aurez généralement pas besoin de vous soucier de ce nom, mais il y a des cas de niche où il peut être utile de comprendre que c'est ce qui se passe.

Si vous devez définir un nom manuellement, vous pouvez utiliser l'annotation CssName pour remplacer le nom par défaut:

@CssName( " my-custom-name " )

val CustomStyle = CssStyle {

base {

Modifier .background( Colors . Red )

}

} Alors, qu'est-ce qui se passe avec le bloc base ?

Certes, il a l'air un peu verbeux en soi. Cependant, vous pouvez définir des blocs de sélection supplémentaires qui prennent effet conditionnellement. Le style de base s'appliquera toujours en premier, mais tout styles supplémentaires sera appliqué en fonction des règles du sélecteur spécifiques.

Prudence

L'ordre compte lors de la définition de sélecteurs supplémentaires, en particulier si plus d'un d'entre eux modifie la même propriété CSS en même temps.

Ici, nous créons un style qui est rouge par défaut mais vert lorsque la souris plane dessus:

val CustomStyle = CssStyle {

base {

Modifier .color( Colors . Red )

}

hover {

Modifier .color( Colors . Green )

}

}Kobweb fournit un tas de sélecteurs standard pour vous pour plus de commodité, mais pour ceux qui sont CSS-Savvy, vous pouvez toujours définir la règle CSS directement pour permettre des combinaisons ou des sélecteurs plus complexes que Kobweb n'a pas encore ajoutés.

Par exemple, cela est identique à la définition de style ci-dessus:

val CustomStyle = CssStyle {

base {

Modifier .color( Colors . Red )

}

cssRule( " :hover " ) {

Modifier .color( Colors . Green )

}

}Il y a une fonctionnalité dans le monde de la conception HTML / CSS réactive appelée point d'arrêt, qui n'a rien à voir avec confusion avec le débogage des points d'arrêt. Ils spécifient plutôt les limites de taille de votre site lorsque les styles changent. C'est ainsi que les sites présentent du contenu différemment sur mobile vs tablette vs bureau.

Kobweb fournit quatre tailles de point d'arrêt que vous pouvez utiliser pour votre projet, qui, y compris en utilisant aucune taille de point d'arrêt, vous donne cinq seaux avec lesquels vous pouvez travailler lors de la conception de votre site:

Vous pouvez modifier les valeurs par défaut des points d'arrêt de votre site en ajoutant une méthode @InitSilk à votre code et en définissant ctx.theme.breakpoints :

@InitSilk

fun initializeBreakpoints ( ctx : InitSilkContext ) {

ctx.theme.breakpoints = BreakpointSizes (

sm = 30 .cssRem,

md = 48 .cssRem,

lg = 62 .cssRem,

xl = 80 .cssRem,

)

} Pour référencer un point de rupture dans un CssStyle , il suffit de l'invoquer:

val CustomStyle = CssStyle {

base {

Modifier .fontSize( 24 .px)

}

Breakpoint . MD {

Modifier .fontSize( 32 .px)

}

}Conseil

Lorsque vous testez vos styles de condition interminable, vous devez savoir que les outils de développement du navigateur vous permettent de simuler les dimensions de la fenêtre pour voir à quoi votre site regarde sur différentes tailles. Par exemple, sur Chrome, vous pouvez suivre ces instructions: https://developer.chrome.com/docs/devtools/device-mode

Vous pouvez également spécifier qu'un style ne doit s'appliquer qu'à une gamme spécifique de points d'arrêt à l'aide des opérateurs de gamme Kotlin:

val CustomStyle = CssStyle {

// The following three declarations are the same, and ensure their style is only active in mobile / tablet modes

// Option 1: exclusive upper bound

( Breakpoint . ZERO .. < Breakpoint . MD ) { Modifier .fontSize( 24 .px) }

// Option 2: using `until` for `..<`

( Breakpoint . ZERO until Breakpoint . MD ) { Modifier .fontSize( 24 .px) }

// Option 3: inclusive upper bound

( Breakpoint . ZERO .. Breakpoint . SM ) { Modifier .fontSize( 24 .px) }

Breakpoint . MD { Modifier .fontSize( 32 .px) }

} Si vous n'êtes pas un fan d'avoir besoin d'envelopper l'expression avec des parenthèses, la méthode between est également fournie, ce qui est par ailleurs identique à l'opérateur ..< Range:

val CustomStyle = CssStyle {

// Style active in mobile / tablet modes

between( Breakpoint . ZERO , Breakpoint . MD ) { /* ... */ }

} Enfin, si le premier point d'arrêt de votre gamme est Breakpoint.ZERO , vous pouvez raccourcir votre expression en utilisant la méthode until la place:

val CustomStyle = CssStyle {

// Style active in mobile / tablet modes

until( Breakpoint . MD ) { /* ... */ }

} En fait, vous pouvez considérer until l'inverse à déclarer un point d'arrêt normal. En d'autres termes, until(Breakpoint.MD) { ... } signifie toutes les tailles de point d'arrêt jusqu'à la taille moyenne, tandis que Breakpoint.MD { ... } signifie la taille moyenne et supérieure.

Lorsque vous définissez un CssStyle , un champ appelé colorMode est disponible pour vous:

val CustomStyle = CssStyle .base {

Modifier .color( if (colorMode.isLight) Colors . Red else Colors . Pink )

} La soie définit un tas de couleurs claires et sombres pour tous ses widgets, et si vous souhaitez réutiliser l'un d'eux dans votre propre widget, vous pouvez les interroger en utilisant colorMode.toPalette() :

val CustomStyle = CssStyle .base {

Modifier .color(colorMode.toPalette().link.default)

} SilkTheme contient des défaillances très simples (par exemple en noir et blanc), mais vous pouvez les remplacer dans une méthode @InitSilk , peut-être à quelque chose qui est plus conscient de la marque:

// Assume a bunch of color constants (e.g. BRAND_LIGHT_COLOR) are defined somewhere

@InitSilk

fun overrideSilkTheme ( ctx : InitSilkContext ) {

ctx.theme.palettes.light.background = BRAND_LIGHT_BACKGROUND

ctx.theme.palettes.light.color = BRAND_LIGHT_COLOR

ctx.theme.palettes.dark.background = BRAND_DARK_BACKGROUND

ctx.theme.palettes.dark.color = BRAND_DARK_COLOR

} Par défaut, Kobweb initialisera le mode couleur de votre site sur ColorMode.LIGHT .

Cependant, vous pouvez contrôler cela en définissant la propriété initialColorMode dans une méthode @InitSilk :

@InitSilk

fun setInitialColorMode ( ctx : InitSilkContext ) {

ctx.theme.initialColorMode = ColorMode . DARK

} Si vous souhaitez respecter les préférences du système de l'utilisateur, vous pouvez définir initialColorMode sur ColorMode.systemPreference :

@InitSilk

fun setInitialColorMode ( ctx : InitSilkContext ) {

ctx.theme.initialColorMode = ColorMode .systemPreference

}Si vous prenez votre prise en charge du mode de couleur du site, vous êtes encouragé à enregistrer le dernier réglage choisi par l'utilisateur dans le stockage local, puis à le restaurer si l'utilisateur revisite votre site plus tard.

La restauration se produira dans votre bloc @InitSilk , tandis que le code pour enregistrer le mode couleur devrait se produire dans votre root @App composable:

@InitSilk

fun setInitialColorMode ( ctx : InitSilkContext ) {

ctx.theme.initialColorMode =

ColorMode .loadFromLocalStorage() ? : ColorMode .systemPreference

}

@App

@Composable

fun AppEntry ( content : @Composable () -> Unit ) {

SilkApp {

val colorMode = ColorMode .current

LaunchedEffect (colorMode) {

colorMode.saveToLocalStorage()

}

/* ... */

}

}Vous pouvez vous retrouver parfois à définir un style qui ne devrait être appliqué qu'avec / après un autre style.

Le moyen le plus simple d'y parvenir est d'étendre le bloc de style CSS de base, en utilisant la méthode extendedBy :

val GeneralTextStyle = CssStyle {

base { Modifier .fontSize( 16 .px).fontFamily( " ... " ) }

}

val EmphasizedTextStyle = GeneralTextStyle .extendedBy {

base { Modifier .fontWeight( FontWeight . Bold ) }

}

// Or, using the `base` methods:

// val GeneralTextStyle = CssStyle.base {

// Modifier.fontSize(16.px).fontFamily("...")

// }

// val EmphasizedTextStyle = GeneralTextStyle.extendedByBase {

// Modifier.fontWeight(FontWeight.Bold)

// } Une fois étendu, il vous suffit d'appeler toModifier sur le style étendu pour inclure automatiquement les deux styles:

SpanText ( " WARNING " , EmphasizedTextStyle .toModifier())

// You do NOT need to reference the base style, i.e.

// GeneralTextStyle.toModifier().then(EmphasizedTextStyle.toModifier()) Jusqu'à présent, nous avons discuté des blocs de style CSS comme définissant un assortiment général de propriétés de style CSS. Cependant, il existe un moyen de définir des blocs de style CSS tapés, qui vous permettent de générer des variantes dactylographiées associées et uniquement avec un style de base spécifique.

Le style de base dans ce cas est appelé style composant car le motif est efficace lors de la définition des composants du widget. En fait, c'est le modèle standard que la soie utilise pour chacun de ses widgets.

Nous discuterons de ce modèle complet autour de la construction de widgets en utilisant des styles de composants plus tard, mais pour commencer, nous allons montrer comment en déclarer un. Vous créez une interface de marqueur qui implémente ComponentKind , puis passez-le dans votre bloc de déclaration CssStyle .

Par exemple, si vous créiez votre propre widget Button :

sealed interface ButtonKind : ComponentKind

val ButtonStyle = CssStyle < ButtonKind > { /* ... */ }Remarquez deux points sur notre déclaration d'interface:

sealed . Ce n'est techniquement pas nécessaire pour le faire, mais nous le recommandons comme un moyen d'exprimer votre intention que personne d'autre ne le sous-classe davantage. Comme les déclarations normales CssStyle , le nom associé est dérivé du nom de sa propriété. Vous pouvez utiliser une annotation @CssName pour remplacer ce comportement.

La puissance des styles de composants est qu'ils peuvent générer des variantes de composants , en utilisant la méthode addVariant :

val OutlinedButtonVariant : CssStyleVariant < ButtonKind > = ButtonStyle .addVariant { /* ... */ }Note

La convention de dénomination recommandée pour les variantes est de prendre leur style associé et d'utiliser son nom comme un suffixe plus le mot "variant", par exemple "Buttonstyle" -> "OutlinedbuttonVariant" et "textStyle" -> "mettant l'accent sur le VETTVariant".

Important

Comme un CssStyle , votre CssStyleVariant doit être public. Ceci est pour la même raison: parce que le code est généré dans un fichier main.kt par le plugin Kobweb Gradle, et ce code doit pouvoir accéder à votre variante afin de l'enregistrer.

Vous pouvez techniquement faire une variante privée si vous ajoutez un peu de passe-partout pour gérer vous-même l'inscription:

@Suppress( " PRIVATE_COMPONENT_VARIANT " )

private val ExampleCustomVariant = ButtonStyle .addVariant {

/* ... */

}

// Or, `private val _ExampleCustomVariant`

@InitSilk

fun registerPrivateVariant ( ctx : InitSilkContext ) {

// When registering variants, using a leading dash will automatically prepend the bast style name.

// This example here will generate the final name "button-example".

ctx.theme.registerVariant( " -example " , ExampleCustomVariant )

}Cependant, vous êtes encouragé à garder vos variantes publiques et à laisser le plugin Kobweb Gradle gérer tout pour vous.

L'idée derrière les variantes des composants est qu'ils donnent au widget l'auteur le pouvoir de définir un style de base avec un ou plusieurs ajustements courants que les utilisateurs pourraient vouloir appliquer par-dessus. (Et même si un auteur de widget ne fournit aucune variante pour le style, tout utilisateur peut toujours définir le sien dans sa propre base de code.)

Revoyons l'exemple de style bouton, réunissant tout.

sealed interface ButtonKind : ComponentKind

val ButtonStyle = CssStyle < ButtonKind > { /* ... */ }

// Note: Creates a CSS style called "button-outlined"

val OutlinedButtonVariant = ButtonStyle .addVariant { /* ... */ }

// Note: Creates a CSS style called "button-inverted"

val InvertedButtonVariant = ButtonStyle .addVariant { /* ... */ } Lorsqu'elle est utilisée avec un style de composant, la méthode toModifier() prend éventuellement un paramètre variant. Lorsqu'une variante est transmise, les deux styles seront appliqués - le style de base suivi du style variant.

Par exemple, ButtonStyle.toModifier(OutlinedButtonVariant) applique le style de bouton principal en premier en haut avec un style de contour supplémentaire.

Vous pouvez annoter les variantes de style avec l'annotation @CssName , exactement comme vous le pouvez avec CssStyle . L'utilisation d'un tableau de bord leader apprendra automatiquement le nom du style de base. Par exemple:

@CssName( " custom-name " )

val OutlinedButtonVariant = ButtonStyle .addVariant { /* ... */ } // Creates a CSS style called "custom-name"

@CssName( " -custom-name " )

val InvertedButtonVariant = ButtonStyle .addVariant { /* ... */ } // Creates a CSS style called "button-custom-name" addVariantBase Like CssStyle.base , variants that don't need to support additional selectors can use addVariantBase instead to slightly simplify their declaration:

val HighlightedCustomVariant by CustomStyle .addVariantBase {

Modifier .backgroundColor( Colors . Green )

}

// Short for

// val HighlightedCustomVariant by CustomStyle.addVariant {

// base { Modifier.backgroundColor(Colors.Green) }

// } Silk uses component styles when defining its widgets, and you can too! The full pattern looks like this:

sealed interface CustomWidgetKind : ComponentKind

val CustomWidgetStyle = CssStyle < CustomWidgetKind > { /* ... */ }

@Composable

fun CustomWidget (

modifier : Modifier = Modifier ,

variant : CssStyleVariant < CustomWidgetKind > ? = null,

@Composable content : () -> Unit

) {

val finalModifier = CustomWidgetStyle .toModifier(variant).then(modifier)

/* ... */

}Autrement dit:

modifier as its first optional parameter.CssStyleVariant parameter (typed to your unique ComponentKind implementation)@Composable context lambda parameter (unless this widget doesn't support custom content)A caller might call your widget one of several ways:

// Approach #1: Use default styling

CustomWidget { /* ... */ }

// Approach #2: Tweak default styling with a variant

CustomWidget (variant = TransparentWidgetVariant ) { /* ... */ }

// Approach #3: Tweak default styling with inline overrides

CustomWidget ( Modifier .backgroundColor( Colors . Blue )) { /* ... */ }

// Approach #4: Tweak default styling with both a variant and inline overrides

CustomWidget ( Modifier .backgroundColor( Colors . Blue ), variant = TransparentWidgetVariant ) { /* ... */ }In CSS, animations work by letting you define keyframes in a stylesheet which you then reference, by name, in an animation style. You can read more about them on Mozilla's documentation site.

For example, here's the CSS for an animation of a sliding rectangle (from this tutorial):

div {

width : 100 px ;

height : 100 px ;

background : red;

position : relative;

animation : shift-right 5 s infinite;

}

@keyframes shift-right {

from { left : 0 px ;}

to { left : 200 px ;}

} Kobweb lets you define your keyframes in code by using a Keyframes block:

val ShiftRightKeyframes = Keyframes {

from { Modifier .left( 0 .px) }

to { Modifier .left( 200 .px) }

}

// Later

Div (

Modifier

.size( 100 .px).backgroundColor( Colors . Red ).position( Position . Relative )

.animation( ShiftRightKeyframes .toAnimation(

duration = 5 .s,

iterationCount = AnimationIterationCount . Infinite

))

.toAttrs()

) The name of the keyframes block is automatically derived from the property name (here, ShiftRightKeyframes is converted into "shift-right" ). You can then use the toAnimation method to convert your collection of keyframes into an animation that uses them, which you can pass into the Modifier.animation modifier.

Important

When you declare a Keyframes animation, it must be public. This is because code gets generated inside a main.kt file by the Kobweb Gradle plugin, and that code needs to be able to access your variant in order to register it.

In general, it's a good idea to think of animations as global anyway, since technically they all live in a globally applied stylesheet, and you have to make sure that the animation name is unique across your whole application.

You can technically make an animation private if you add a bit of boilerplate to handle the registration yourself:

@Suppress( " PRIVATE_KEYFRAMES " )

private val ExampleKeyframes = Keyframes { /* ... */ }

// Or, `private val _ExampleKeyframes`

@InitSilk

fun registerPrivateAnim ( ctx : InitSilkContext ) {

ctx.stylesheet.registerKeyframes( " example " , ExampleKeyframes )

}However, you are encouraged to keep your keyframes public and let the Kobweb Gradle plugin handle everything for you.

Occasionally, you may need access to the raw element backing the Silk widget you've just created. All Silk widgets provide an optional ref parameter which takes a listener that provides this information.

Box (

ref = /* ... */

) {

/* ... */

} All ref callbacks (discussed more below) will receive an org.w3c.dom.Element subclass. You can check out the Element class (and its often more relevant HTMLElement inheritor) to see the methods and properties that are available on it.

Raw HTML elements expose a lot of functionality not available through the higher-level Compose HTML APIs.

refFor a trivial but common example, we can use the raw element to capture focus:

Box (

ref = ref { element ->

// Triggered when this Box is first added into the DOM

element.focus()

}

) The ref { ... } method can actually take one or more optional keys of any value. If any of these keys change on a subsequent recomposition, the callback will be rerun:

val colorMode by ColorMode .currentState

Box (

// Callback will get triggered each time the color mode changes

ref = ref(colorMode) { element -> /* ... */ }

)disposableRef If you need to know both when the element enters AND exits the DOM, you can use disposableRef instead. With disposableRef , the very last line in your block must be a call to onDispose :

val activeElements : MutableSet < HTMLElement > = /* ... */

/* ... later ... */

Box (

ref = disposableRef { element ->

activeElements.put(element)

onDispose { activeElements.remove(element) }

}

) The disposableRef method can also take keys that rerun the listener if any of them change. The onDispose callback will also be triggered in that case, as the old effect gets discarded.

refScope And, finally, you may want to have multiple listeners that are recreated independently of one another based on different keys. You can use refScope as a way to combine two or more ref and/or disposableRef calls in any combination:

val isFeature1Enabled : Boolean = /* ... */

val isFeature2Enabled : Boolean = /* ... */

Box (

ref = refScope {

ref(isFeature1Enabled) { element -> /* ... */ }

disposableRef(isFeature2Enabled) { element -> /* ... */ ; onDispose { /* ... */ } }

}

) You may occasionally want the backing element of a normal Compose HTML widget, such as a Div or Span . However, these widgets don't have a ref callback, as that's a convenience feature provided by Silk.

You still have a few options in this case.

The official way to retrieve a reference is by using a ref block inside an attrs block. This version of ref is actually more similar to Silk's disposableRef concept than its ref one, as it requires an onDispose block:

Div (attrs = {

ref { element -> /* ... */ ; onDispose { /* ... */ } }

})The above snippet was adapted from the official tutorials.

You could put that exact same logic inside the Modifier.toAttrs block if you're terminating some modifier chain:

Div (attrs = Modifier .toAttrs {

ref { element -> /* ... */ ; onDispose { /* ... */ } }

}) Unlike Silk's version of ref , Compose HTML's version does not accept keys. If you need this behavior and if the Compose HTML widget accepts a content block (many of them do), you can call Silk's registerRefScope method directly within it:

Div {

registerRefScope(

disposableRef { element -> /* ... */ ; onDispose { /* ... */ } }

// or ref { element -> /* ... */ }

)

} Kobweb supports CSS variables (also called CSS custom properties), which is a feature where you can store and retrieve property values from variables declared within your CSS styles. It does this through a class called StyleVariable .

Note

You can find official documentation for CSS custom properties here.

Using style variables is fairly simple. You first declare one without a value (but lock it down to a type) and later you can initialize it within a style using Modifier.setVariable(...) :

val dialogWidth by StyleVariable < CSSLengthNumericValue >()

// This style will be applied to a div that lives at the root, so that

// this variable value will be made available to all children.

val RootStyle = CssStyle .base {

Modifier .setVariable(dialogWidth, 600 .px)

}Conseil

Compose HTML provides a CSSLengthValue , which represents concrete values like 10.px or 5.cssRem . However, Kobweb provides a CSSLengthNumericValue type which represents the concept more generally, eg as the result of intermediate calculations. There are CSS*NumericValue types provided for all relevant units, and it is recommended to use them when declaring style variables as they more naturally support being used in calculations.

We discuss CSSNumericValue types▼ in more detail later in this document.

You can later query variables using the value() method to extract their current value:

val DialogStyle = CssStyle .base {

Modifier .width(dialogWidth.value())

}You can also provide a fallback value, which, if present, would be used in the case that a variable hadn't already been set previously:

val DialogStyle = CssStyle .base {

// Will be the value of the dialogWidth variable if it was set, otherwise 500px

Modifier .width(dialogWidth.value( 500 .px))

}Additionally, you can also provide a default fallback value when declaring the variable:

// Note the default fallback: 100px

val dialogWidth by StyleVariable < CSSLengthNumericValue >( 100 .px)

val DialogStyle100 = CssStyle .base {

// Uses default fallback. width = 100px

Modifier .width(dialogWidth.value())

}

val DialogStyle200 = CssStyle .base {

// Uses specific fallback. width = 200px

Modifier .width(dialogWidth.value( 200 .px))

}

val DialogStyle300 = CssStyle .base {

// Fallback (400px) ignored because variable is set explicitly. width = 300px

Modifier .setVariable(dialogWidth, 300 .px).width(dialogWidth.value( 400 .px))

}Prudence

In the above example in the DialogStyle300 style, we set a variable and query it in the same line, which we did purely for demonstration purposes. In practice, you would probably never do this -- the variable would have been set separately elsewhere, eg in an inline style or on a parent container.

To demonstrate these concepts all together, below we declare a background color variable, create a root container scope which sets it, a child style that uses it, and, finally, a child style variant that overrides it:

// Default to a debug color, so if we see it, it indicates we forgot to set it later

val bgColor by StyleVariable < CSSColorValue >( Colors . Magenta )

val ContainerStyle = CssStyle .base {

Modifier .setVariable(bgColor, Colors . Blue )

}

val SquareStyle = CssStyle .base {

Modifier .size( 100 .px).backgroundColor(bgColor.value())

}

val RedSquareStyle = SquareStyle .extendedByBase {

Modifier .setVariable(bgColor, Colors . Red )

}The following code brings the above styles together (and in some cases uses inline styles to override the background color further):

@Composable

fun ColoredSquares () {

Box ( ContainerStyle .toModifier()) {

Column {

Row {

// 1: Read color from ContainerStyle

Box ( SquareStyle .toModifier())

// 2: Override color via RedSquareStyle

Box ( RedSquareStyle .toModifier())

}

Row {

// 3: Override color via inline styles

Box ( SquareStyle .toModifier().setVariable(bgColor, Colors . Green ))

Span ( Modifier .setVariable(bgColor, Colors . Yellow ).toAttrs()) {

// 4: Read color from parent's inline style

Box ( SquareStyle .toModifier())

}

}

}

}

}The above renders the following output:

You can also set CSS variables directly from code if you have access to the backing HTML element. Below, we use the ref callback to get the backing element for a fullscreen Box and then use a Button to set it to a random color from the colors of the rainbow:

// We specify the initial color of the rainbow here, since the variable

// won't otherwise be set until the user clicks a button.

val bgColor by StyleVariable < CSSColorValue >( Colors . Red )

val ScreenStyle = CssStyle .base {

Modifier .fillMaxSize().backgroundColor(bgColor.value())

}

@Page

@Composable

fun RainbowBackground () {

val roygbiv = listOf ( Colors . Red , /* ... */ Colors . Violet )

var screenElement : HTMLElement ? by remember { mutableStateOf( null ) }

Box ( ScreenStyle .toModifier(), ref = ref { screenElement = it }) {

Button (onClick = {

// You can call `setVariable` on the backing HTML element to set the variable value directly

screenElement !! .setVariable(bgColor, roygbiv.random())

}) {

Text ( " Click me " )

}

}

}The above results in the following UI:

Most of the time, you can actually get away with not using CSS Variables! Your Kotlin code is often a more natural place to describe dynamic behavior than HTML / CSS is.

Let's revisit the "colored squares" example from above. Note it's much easier to read if we don't try to use variables at all.

val SquareStyle = CssStyle .base {

Modifier .size( 100 .px)

}

@Composable

fun ColoredSquares () {

Column {

Row {

Box ( SquareStyle .toModifier().backgroundColor( Colors . Blue ))

Box ( SquareStyle .toModifier().backgroundColor( Colors . Red ))

}

Row {

Box ( SquareStyle .toModifier().backgroundColor( Colors . Green ))

Box ( SquareStyle .toModifier().backgroundColor( Colors . Yellow ))

}

}

} And the "rainbow background" example is similarly easier to read by using Kotlin variables (ie var someValue by remember { mutableStateOf(...) } ) instead of CSS variables:

val ScreenStyle = CssStyle .base {

Modifier .fillMaxSize()

}

@Page

@Composable

fun RainbowBackground () {

val roygbiv = listOf ( Colors . Red , /* ... */ Colors . Violet )

var currColor by remember { mutableStateOf( Colors . Red ) }

Box ( ScreenStyle .toModifier().backgroundColor(currColor)) {

Button (onClick = { currColor = roygbiv.random() }) {

Text ( " Click me " )

}

}

}Even though you should rarely need CSS variables, there may be occasions where they can be a useful tool in your toolbox. The above examples were artificial scenarios used as a way to show off CSS variables in relatively isolated environments. But here are some situations that might benefit from CSS variables:

themePrimary and themeSecondary (applied at the site's root) which you can then reference throughout your styles.When in doubt, lean on Kotlin for handling dynamic behavior, and occasionally consider using style variables if you feel doing so would clean up the code.

Kobweb provides the silk-icons-fa artifact which you can use in your project if you want access to all the free Font Awesome (v6) icons.

Using it is easy! Search the Font Awesome gallery, choose an icon, and then call it using the associated Font Awesome icon composable.

For example, if I wanted to add the Kobweb-themed spider icon, I could call this in my Kobweb code:

FaSpider ()C'est ça!

Some icons have a choice between solid and outline versions, such as "Square" (outline and filled). In that case, the default choice will be an outline mode, but you can pass in a style enum to control this:

FaSquare (style = IconStyle . FILLED )All Font Awesome composables accept a modifier parameter, so you can tweak it further:

FaSpider ( Modifier .color( Colors . Red ))Note

When you create a project using our app template, Font Awesome icons are included.

Kobweb provides the silk-icons-mdi artifact which you can use in your project if you want access to all the free Material Design icons.

Using it is easy! Search the Material Icons gallery, choose an icon, and then call it using the associated Material Design Icon composable.

For example, let's say after a search I found and wanted to use their bug report icon, I could call this in my Kobweb code by converting the name to camel case:

MdiBugReport ()C'est ça!

Most material design icons support multiple styles: outlined, filled, rounded, sharp, and two-tone. Check the gallery search link above to verify what styles are supported by your icon. You can identify the one you want to use by passing it into the method's style parameter:

MdiLightMode (style = IconStyle . TWO_TONED )All Material Design Icon composables accept a modifier parameter, so you can tweak it further:

MdiError ( Modifier .color( Colors . Red ))Outside of pages, it is common to create reusable, composable parts. While Kobweb doesn't enforce any particular rule here, we recommend a convention that, if followed, may make it easier to allow new readers of your codebase to get around.

First, as a sibling to pages, create a folder called components . Within it, add:

@Page pages will start by calling a page layout function first. It's possible that you will only need a single layout for your entire site. If you create a markdown file under the jsMain/resources/markdown folder, a corresponding page will be created for you at build time, using the filename as its path.

For example, if I create the following file:

// jsMain/resources/markdown/docs/tutorial/Kobweb.md

# Kobweb Tutorial

... this will create a page that I can then visit by going to mysite.com/docs/tutorial/kobweb

Front Matter is metadata that you can specify at the beginning of your document, like so:

---

title : Tutorial

author : bitspittle

---

...In a following section, we'll discuss how to embed code in your markdown, but for now, know that these key / value pairs can be queried in code using the page's context:

@Composable

fun AuthorWidget () {

val ctx = rememberPageContext()

// Note: You can use `markdown!!` only if you're sure that

// this composable is called while inside a page generated

// from Markdown.

val author = ctx.markdown !! .frontMatter.getValue( " author " ).single()

Text ( " Article by $author " )

}Important

If you're not seeing ctx.markdown autocomplete, you need to make sure you depend on the com.varabyte.kobwebx:kobwebx-markdown artifact in your project's build.gradle .

Within your front matter, there's a special value which, if set, will be used to render a root @Composable that adds the rest of your markdown code as its content. This is useful for specifying a layout for example:

---

root : .components.layout.DocsLayout

---

# Kobweb TutorialThe above will generate code like the following:

import com.mysite.components.layout.DocsLayout

@Composable

@Page

fun KobwebPage () {

DocsLayout {

H1 {

Text ( " Kobweb Tutorial " )

}

}

}If you have a default root that you'd like to use in most / all of your markdown files, you can specify it in the markdown block in your build script:

// site/build.gradle.kts

kobweb {

markdown {

defaultRoot.set( " .components.layout.MarkdownLayout " )

}

} Kobweb Markdown front matter supports a routeOverride key. If present, its value will be passed into the generated @Page annotation (see the Route Override section▲ for valid values here).

This allows you to give your URL a name that normal Kotlin filename rules don't allow for, such as a hyphen:

# AStarDemo.md

---

routeOverride : a*-demo

---The above will generate code like the following:

@Composable

@Page( " a*-demo " )

fun AStarDemoPage () { /* ... */

}The power of Kotlin + Compose HTML is interactive components, not static text! Therefore, Kobweb Markdown support enables special syntax that can be used to insert Kotlin code.

Usually, you will define widgets that belong in their own section. Just use three triple-curly braces to insert a function that lives in its own block:

# Kobweb Tutorial

...

{{{ .components.widgets.VisitorCounter }}}which will generate code for you like the following:

@Composable

@Page

fun KobwebPage () {

/* ... */

com.mysite.components.widgets. VisitorCounter ()

} You may have noticed that the code path in the markdown file is prefixed with a . . When you do that, the final path will automatically be prepended with your site's full package.

Occasionally, you may want to insert a smaller widget into the flow of a single sentence. For this case, use the ${...} inline syntax:

Press ${.components.widgets.ColorButton} to toggle the site's current color.Prudence

Spaces are not allowed within the curly braces! If you have them there, Markdown skips over the whole thing and leaves it as text.

You may wish to add imports to the code generated from your markdown. Kobweb Markdown supports registering both global imports (imports that will be added to every generated file) and local imports (those that will only apply to a single target file).

To register a global import, you configure the markdown block in your build script:

// site/build.gradle.kts

kobweb {

markdown {

imports.add( " .components.widgets.* " )

}

}Notice that you can begin your path with a "." to tell the Kobweb Markdown plugin to prepend your site's package to it. The above would ensure that every markdown file generated would have the following import:

import com.mysite.components.widgets.*Imports can help you simplify your Kobweb calls. Revisiting an example from just above:

# Without imports

Press ${.components.widgets.ColorButton} to toggle the site's current color.

# With imports

Press ${ColorButton} to toggle the site's current color.Local imports are specified in your markdown's front matter (and can even affect its root declaration!):

---

root : DocsLayout

imports :

- .components.sections.DocsLayout

- .components.widgets.VisitorCounter

---

...

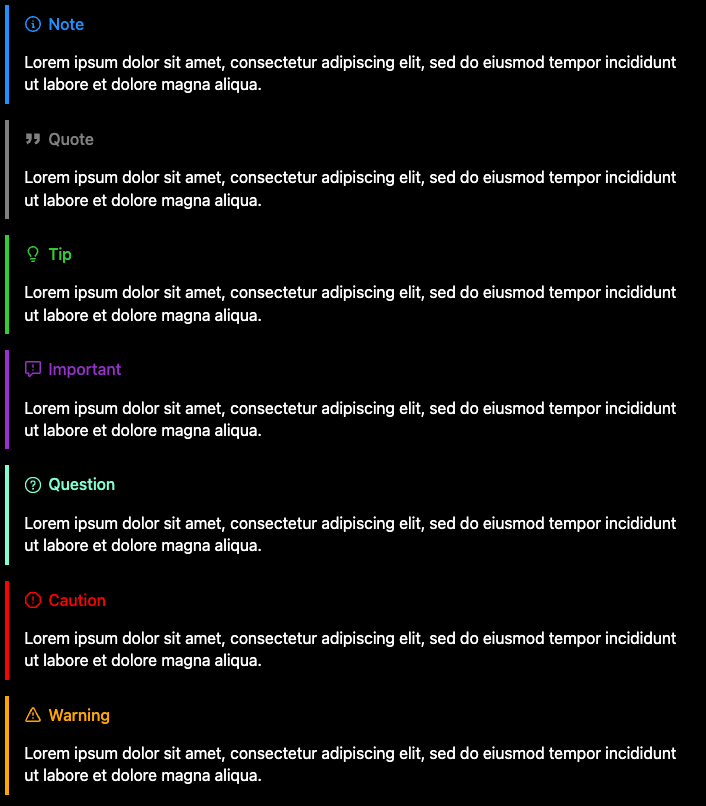

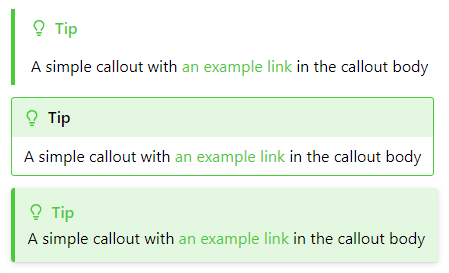

{{{ VisitorCounter }}}Kobweb Markdown supports callouts, which are a way to highlight pieces of information in your document. For example, you can use them to highlight notes, tips, warnings, or important messages.

To use a callout, set the first line of some blockquoted text to [!TYPE] , where TYPE is one of the following:

> [ !NOTE ]

> Lorem ipsum...

> [ !QUOTE ]

> Lorem ipsum...

If you'd like to change the value of the default title that shows up, you can specify it in quotes:

> [ !QUESTION "Something to ponder..." ]As another example, when using quotes, you can set this to the empty string, which looks clean:

> [ !QUOTE "" ]

> ...

If you want to specify a label that should apply globally, you can do so by overriding the blockquote handler in your project's build script, using the convenience method SilkCalloutBlockquoteHandler for it:

kobweb {

markdown {

handlers.blockquote.set( SilkCalloutBlockquoteHandler (labels = mapOf ( " QUOTE " to " " )))

}

}Prudence

Callouts are provided by Silk. If your project does not use Silk and you override the blockquote handler like this, it will generate code that will cause a compile error.

Silk provides a handful of variants for callouts.

For example, an outlined variant:

and a filled variant:

You can also combine any of the standard variants with an additional matching link variant (eg LeftBorderedCalloutVariant.then(MatchingLinkCalloutVariant)) ) to make it so that any hyperlinks inside the callout will match the color of the callout itself:

If you prefer any of these styles over the default, you can set the variant parameter in the SilkCalloutBlockquoteHandler , for example here we set it to the outlined variant:

kobweb {

markdown {

handlers.blockquote.set( SilkCalloutBlockquoteHandler (

variant = " com.varabyte.kobweb.silk.components.display.OutlinedCalloutVariant " )

)

}

}Of course, you can also define your own variant in your own codebase and pass that in here as well.

If you'd like to register a custom callout, this is done in two parts.

First, declare your custom callout setup in your code somewhere:

package com.mysite.components.widgets.callouts

val CustomCallout = CalloutType (

/* ... specify icon, label, and colors here ... */

) and then register it in your build script, extending the default list of handlers (ie SilkCalloutTypes ) with your custom one:

kobweb {

markdown {

handlers.blockquote.set(

SilkCalloutBlockquoteHandler (types =

SilkCalloutTypes +

mapOf ( " CUSTOM " to " .components.widgets.callouts.CustomCallout " )

)

)

}

}Note

As seen above, by using a leading . , you can omit your project's group (eg com.mysite ). Kobweb will automatically prepend it for you.

C'est ça! At this point, you can use it in your markdown:

> [ !CUSTOM ]

> Neat.It can be really useful to process all markdown files during your site's build. A common example is to collect all markdown articles and generate a listing page from them.

You can actually do this using pure Gradle code, but it's common enough that Kobweb provides a convenience API, via the markdown block's process callback.

You can register a callback that will be triggered at build time with a list of all markdown files in your project.

kobweb {

markdown {

process.set { markdownEntries ->

// `markdownEntries` is type `List<MarkdownEntry>`, where an entry includes the file's path, the route it will

// be served at, and any parsed front matter.

println ( " Processing markdown files: " )

markdownEntries.forEach { entry ->

println ( " t * ${entry.filePath} -> ${entry.route} " )

}

}

}

} Inside the callback, you can also call generateKotlin and generateMarkdown utility methods. Here is a very rough example of creating a listing page for all blog posts in a site (found under the resources/markdown/blog folder):

kobweb {

markdown {

process.set { markdownEntries ->

generateMarkdown( " blog/index.md " , buildString {

appendLine( " # Blog Index " )

markdownEntries.forEach { entry ->

if (entry.filePath.startsWith( " blog/ " )) {

val title = entry.frontMatter[ " title " ] ? : " Untitled "

appendLine( " * [ $title ]( ${entry.route} ) " )

}

}

})

}

}

}Refer to the build script of my open source blog site and search for "process.set" to see this feature in action in a production environment.

Many developers new to web development have heard horror stories about CSS, and they might hope that Kobweb, by leveraging Kotlin and a Jetpack Compose-inspired API, means they won't have to learn it.

It's worth dispelling that illusion! CSS is inevitable.

That said, CSS's reputation is probably worse than it deserves to be. Many of its features are actually fairly straightforward and some are quite powerful. For example, you can efficiently declare that your element should be wrapped with a thin border, with round corners, casting a drop shadow beneath it to give it a feeling of depth, painted with a gradient effect for its background, and animated with an oscillating, tilting effect.

It's hoped that, once you've learned a bit of CSS through Kobweb, you'll find yourself actually enjoying it (sometimes)!

Kobweb offers enough of a layer of abstraction that you can learn CSS in a more incremental way.

First and most importantly, Kobweb gives you a Kotlin-idiomatic type-safe API to CSS properties. This is a major improvement over writing CSS in text files which fail silently at runtime.

Next, layout widgets like Box , Column , and Row can get you up and running quickly with rich, complex layouts before ever having to understand what a "flex layout" is.

Meanwhile, using CssStyle can help you break your CSS up into smaller, more manageable pieces that live close to the code that actually uses them, allowing your project to avoid a giant, monolithic CSS file. (Such giant CSS files are one of the reasons CSS has an intimidating reputation).

For example, a CSS file that could easily look like this:

/* Dozens of rules... */

. important {

background-color : red;

font-weight : bold;

}

. important : hover {

background-color : pink;

}

/* Dozens of other rules... */

. post-title {

font-size : 24 px ;

}

/* A dozen more more rules... */can migrate to this in Kobweb:

// ------------------ CriticalInformation.kt

val ImportantStyle = CssStyle {

base {

Modifier .backgroundColor( Colors . Red ).fontWeight( FontWeight . Bold )

}

hover {

Modifier .backgroundColor( Colors . Pink )

}

}

// ------------------ Post.kt

val PostTitleStyle = CssStyle .base { Modifier .fontSize( 24 .px) } Next, Silk provides a Deferred composable which lets you declare code that won't get rendered until the rest of the DOM finishes first, meaning it will appear on top of everything else. This is a clean way to avoid setting CSS z-index values (another aspect of CSS that has a bad reputation).

And finally, Silk aims to provide widgets with default styles that look good for many sites. This means you should be able to rapidly develop common UIs without running into some of the more complex aspects of CSS.

Let's walk through an example of layering CSS effects on top of a basic element.

Conseil

Two of the best learning resources for CSS properties are https://developer.mozilla.org and https://www.w3schools.com . Keep an eye out for these when you do a web search.

We'll create the bordered, floating, oscillating element we discussed earlier. Rereading it now, here are the concepts we need to figure out how to do:

Let's say we want to create an attention grabbing "welcome" widget on our site. You can always start with an empty box, which we'll put some text in:

Box ( Modifier .padding(topBottom = 5 .px, leftRight = 30 .px)) {

Text ( " WELCOME!! " )

}

Create a border

Next, search the internet for "CSS border". One of the top links should be: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/CSS/border

Skim the docs and play around with the interactive examples. With an understanding of the border property now, let's use code completion to discover the Kobweb version of the API:

Box (

Modifier

.padding(topBottom = 5 .px, leftRight = 30 .px)

.border( 1 .px, LineStyle . Solid , Colors . Black )

) {

Text ( " WELCOME!! " )

}

Round out the corners

Search for "CSS rounded corners". It turns out the CSS property in this case is called a "border radius": https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/CSS/border-radius

Box (