介绍

第1课 - 开始

第2课 - 您需要知道的一切

第3课 - 组织

第4课 - 更多相同

第5课 - 将所有内容放在一起

第6课 - 世界围绕着你

学习处理是一本用于处理的介绍性工作簿/教科书,它是在Java顶部建立的。

但是,没有学习P5.JS书,这意味着没有基于JavaScript的学习处理版本。只有Dan Shiffman的学习处理代码移植到P5.js。尽管这本书看起来可能是在目标上,并且通常推荐这本书作为P5.js的介绍。

此存储库是一种解决该问题的尝试。我将浏览学习处理书,链接到适当的Shiffman P5.JS存储簿中的链接,链接到最相关的编码火车视频,并发布我自己的练习代码。

当书中未涵盖的相关主题时,我还会偶尔会出现“绕道”。例如,命令行,使用github等。这些“弯路”可能最终会淹没项目的初始目标,但我们会看到。

我认为这将有助于我的学习过程,希望这对偶然发现此存储库的其他人有帮助。

我开始认为这可能成为类似于Odin Project或FreecodeCamp的开源项目。

也许可以在徽标,西摩·帕特特(Seymour Papert)和学习编码方式的历史上进行部分?首先,这启发了处理。

另请参见约翰·梅达(John Maeda)的数字设计 - 将艺术和技术捆绑在一起,并将计算机本身视为一种艺术媒介。

该视频关于响应式编程的视频启发了John Resig在可汗学院的课程。

P5.JS当前正在从事响应式编程工作吗?我想我可能已经看过一个视频。检查Dan Shiffman的Brickbreaker的视频。

D用于数字。使用这本书的普林斯顿课程。较新的班级网站。了解数字世界看起来D的更新版本是用于数字世界。 - 有趣的是,此介绍性类中不允许使用笔记本电脑,即使这是编码的类

布雷特·维克多(Bret Victor)对可汗学院(Khan Academy)和加工的批评也非常启发。很长。我必须阅读几次。

文章的一些注释:

请参阅此编码火车视频,以了解Dan Shiffman对P5.JS起源的解释,以及如何使用P5.JS进行编码。

请注意,以上视频引用以后已弃用的编辑器。

Dan Shiffman的下一个视频是关于P5.JS工作流程,这意味着如何下载项目文件,如何设置Node.js和Package Manager以及如何在计算机上运行本地服务器。我计划稍后再进行所有这些步骤,但是现在,我将使用在线编辑器。

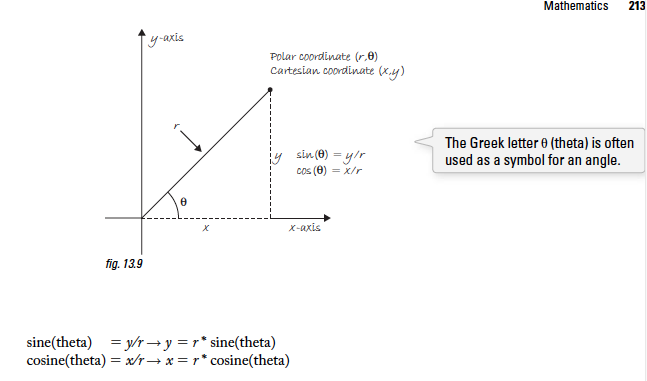

学习图形坐标可能很困难。 0,0在左上

Processing(2001) - 由Casey Reas和Ben Fry开始 - 创建了一个工具,以帮助他们在MIT上的工作(MIT Media Lab的数字设计源自设计)

“创意编码” - 通过编码的创意应用 - 通过计算工具的创造性表达

学习编程很强大 - 不必使用其他人创建的软件被卡住 - 可以自己制作

还可以在Web Processing使用的Java上发布和分发您的创作(称为applet)将在Web浏览器中运行 - 然后是有道理的

现在没有意义 - 错误消息城市的语言是JavaScript

新项目 - 如果今天正在创建处理 - 您会选择哪种语言?

劳伦·麦卡锡(Lauren McCarthy)-JavaScript

processing.js-不要混淆-John Resig- Java翻译为JavaScript

RESIG创建了JQuery和Khan Academy编码课程SO -P5.JS是一个简单,初学者的学习JavaScript的环境,以在浏览器中进行应用程序(创意表达)

要使事情发生在浏览器中,您还需要HTML,CSS,但我们将其留下来供以后使用

处理是“建在Java之上”

P5.js是功能的“库”

如果您想学习JavaScript,则有一百万个资源 - 堆栈溢出,jQuery,文章,书籍

P5.js是一个沙盒,围墙花园

您将获得一组功能来学习编程的一些初学者步骤

这也被称为“一次一步”方法。

这也可以称为“自上而下的设计”。

不要一次尝试做太多。将较大的视力分解为较小的部分,并缓慢攻击每件零件。

太空入侵者示例:

(编者注 - 这可能是一个完全不合适的项目,取决于编码人员的技能水平。故意实践的哲学决定,最好通过具有挑战性的练习来完成学习,但并不是太具有挑战性的。我很难在学习编码的正确平衡。在编码的编码中,这两个项目都太容易了,或者他们不太难过(我都可以找到一个艰难的努力来努力地努力地找到一个综上的努力),而我可以找到一定的努力。

请参阅Shiffman编码太空入侵者的链接 - 似乎并不那么友好)

回到太空入侵者...

然后将问题分为必要的最小部分。简单简便的步骤将使编程游戏看起来更加可实现(您如何弄清楚这些步骤是另一个重要问题)。

我们将第1步分为六个程序。第一个程序将显示一个三角形。每个步骤都会增加一个小改进。下一个将移动三角形。

(当然,能够弄清楚这些步骤已经假设了大量的编码知识。如果您无法弄清楚这些步骤的顺序,甚至首先应该有哪些步骤,那么您有什么机会编写代码执行它们?)

这使得编程和“调试”更加容易 - 接下来会有更多内容。

增量开发也非常适合面向对象的编程,这使我们能够以模块化的形式开发项目,这意味着这些零件可以很容易地组织,共享和重复使用。

有关调试的更多信息,请参见P5.js和ITP的此链接的此链接。

请注意,“错误”是“代码既存在技术问题的时刻,也是您对代码中发生的事情的心理图片的问题。”

我想深入研究。

我看到的大多数调试课程和教程都集中在上述上 - 即首先了解代码在尝试修复之前所做的事情。

这似乎是合乎逻辑的,但它忘记了一个真正的新手可能会在树林中完全迷失的事实。即使新手可以理解代码中发生的事情(一个很大),该程序员也可能没有解决问题的技能。除此之外,以前“有效”的所有步骤实际上可能是当前问题的原因。新手无法知道发生了什么。

此外,除非新手在课程中,或者有另一个网络需要依靠,否则他或她一个人都可以找到“错误”。这最终可能是一项绝望的努力。

这使我的早期要回到了我的早期,这是在正确的难度级别寻找项目的重要性。此外,新手要么需要知道如何在线查找答案(例如,stackoverflow),要么需要一个人网络来寻求帮助)。否则将有一系列失败的项目。

DANS在PRANDLN上的视频。提醒我,其他处理视频可能很有用。

DevTools中的Chrome调试工具

编程都是关于编写算法。

算法是解决特定问题的指令的顺序列表。增量开发应该使编写实现您想法的算法更容易。

(我一直在想算法开发过程。人们如何善于开发基本算法,例如上面的算法,例如在编程中进行的练习?它是否是一种天生的技能?是否可以磨练他们的天生技能,也许他们可以在数学和逻辑上更加自然地学习algorith the Algorith the Algorith the Algorith the Algorithm forne forme with Algorith the Algorithm?从第一原则的角度来看,您的逻辑思维技巧是prec的,甚至是哲学上,您如何编写导致更大程序的伪码的第一行?

请参阅此链接,以了解我对牙刷算法练习的答案。

如果找到此页面,则至少必须知道如何找到GitHub。您甚至可能有一个github个人资料。这些是一个很好的第一步。

查看Dan Shiffman的此视频系列,以介绍GitHub和命令行的介绍。

我记得第一次与终端一起工作时非常恐吓。这对我来说很重要。成为“真正的”程序员的第一个真正的转折点。也许你会同样的感觉。

观看JavaScript中编程的基础-P5.js,视频1.3-2.1。这涵盖了像素,绘制基础知识(形状和颜色),上传p5.js草图以及鼠标和鼠标变量。

这是丹·希夫曼(Dan Shiffman)绘制基本形状的存储库。请注意,这些初始示例写在“设置”功能中。这是因为Dan试图遵循本书的顺序,其中首先教“静态”草图,而“流”直到第3章才引入。

这是Dan的静态外星人角色素描,称为“ Zoog”。

软件发生在一段时间内 - 我们将其称为流程。

什么是设置?

什么是抽奖?

使用设置并绘制功能,请参阅此链接以获取“ Zoog”。

请参阅此链接,以获取我在P5.js中的第一个草图。这是学习处理书中的练习3.2。我已经使用了设置并绘制功能。我使用的唯一形状函数是椭圆和矩形。我画了一条叫做“ Fido”的狗。

我们可以键入鼠标和鼠标,而不是将数字键入我们的功能(RECT,椭圆形),而是指示鼠标光标的水平和垂直位置。

Dan指出了一个有趣的例子,说明当您在设置中放置背景而不是绘制时会发生什么。他还在其中一个视频中讨论了这一点。如果您将背景放置在设置而不是绘制中,则仅绘制背景一次。根据您的程序的意图,这可能是一件好事或坏事。如果您打算设计绘画程序,这很棒,因为背景仅绘制一次,并且随后的每个绘图功能都会显示在画布上。例如,当该形状移动时,您会看到每次在画布上绘制形状的漫长的踪迹。如果您不打算每次在画布上绘制形状时显示,则需要将背景放入Draw功能中,因此每次其他形状都在绘制内部时都会重新绘制背景。与往常一样,丹在解释这一点方面做得比以往任何时候都做得更好。

下一个练习是使我们的绘画用鼠标移动。丹的素描在这里。

我的例子在这里。请注意,该书还提到根据鼠标位置改变颜色,因此我使用colormode()使最小RGB的宽度为0,而最大rgb则是帆布宽度,然后我根据鼠标更改了眼睛和鼻子的填充。

起初我有点挣扎着这个练习。特别是,我之所以挣扎,是因为我将push()和pop()用于草图的旋转“耳朵” - 见下文。

只有在观看了Dan的翻译,旋转等视频之后,我才能完成3.5练习。

请注意,即使我认为这本书中没有提到这一点,但Dan也有素描。

与“ Zoog”不同,我的图纸需要一个特殊的功能 - 与屏幕相关的矩形形状的耳朵。这可以追溯到我提出的那一点 - 在开始项目之前不知道自己会进入什么。我搜索了“用简单形状的画狗”,在网上找到了一个由圆形和矩形制成的狗的图像,并认为我可以在p5.js中绘制它。当然,这并不容易。

在编程中,没有什么简单。从来没有直线要遵循。似乎简单的一切总是变得复杂。当您是初学者并且您正在努力地知道从哪里开始故障排除过程时,更无限的是。

也许有一些关于禅宗的书,享受挫败感 /将障碍视为机遇将在编码课程中有用。我听说麻省理工学院的埃里克·格里森(Eric Grimson)教授使用“挑战的机会”一词。也许这是任何编码员需要拥抱的心态。还有其他考虑。

幸运的是,我已经在转变,轮换,推动和流行音乐方面挣扎着,所以这对我来说并不是外国领土。我能够画草图,旋转的耳朵和所有。我想知道这是否会影响以后的章节未来的项目。总是担心。

请参阅这些编码火车视频,以了解Dan关于旋转图像的课程。

这些代表“以前的”鼠标和小鼠位置,这意味着鼠标的最后一个位置是当我们循环绘制时。

使用pmousex和pmousey的示例:

鼠标点击是事件- 这意味着添加一个与设置分开的新功能并绘制

此新功能将在事件发生时告诉程序要执行什么代码。

与设置类似,它将发生一次,仅一次 - 对于事件的每个事件 - 当然可以在程序过程中多次发生。

两个新功能:

此示例演示了两个事件函数 - 每当按下Ouse并在按下键时清除背景时,添加正方形。

Framerate()需要一个整数在1到60之间,并强制P5.js通过draw()循环的速度。 Framerate(30)表示每秒30帧,是计算机动画的传统速度。如果您不包括Framerate(),则P5将尝试以每秒60帧的速度运行草图。由于计算机以不同的速度运行,因此使用Framerate()来确保您的草图在多台计算机中保持一致。

这是Dan的互动Zoog草图。 Zoog的整个身体都遵循鼠标。它的眼睛颜色取决于鼠标位置。它的腿从以前的鼠标位置到当前的鼠标位置。最后,当单击鼠标时,该消息将显示在控制台中:“带我去找您的领导者!”

本课程的最后一个项目是使用我们从第1到第3章中学到的所有内容绘制新草图。

这必须包括RGB颜色,形状,设置和绘制,以及使用Mousepressed()或KeyPress()函数的某些相互作用。

我画了一个白天原始场景的房子的草图,但是当鼠标被按下时,它会变成夜间。

我将需要一个变量才能通过另一个鼠标单击将其重新更改为白天,但这是下一个课程的主题。

我还考虑过将循环用于绘画星星和使用随机功能之类的东西,但是我决定等到这本书中的这些函数。

本节涵盖:

概述:

该视频是Dan在P5.J.中的变量介绍。

描述变量的类比的洗衣清单:

(请注意,这份90亿美元案件中的律师试图将Java的API与档案柜进行比较。解释技术很难。这就是为什么编码列车如此之大的原因。)

计算机有内存。变量是指向计算机内存中位置(一个“内存地址”)中的位置的指针。

计算机一次仅处理一项指令。因此,变量允许程序员从程序中的一个点保存信息,并在以后的时间引用。

示例:

丹说,他更喜欢纸的方法:格纹纸。

想象一下计算机的内存作为一张图形纸,而平面纸上的每个单元格都有一个地址。使用变量,我们可以命名这些单元格。

让我们命名一个“ Dan的分数”,并给它一个100的值。然后,当我们想在Progran中使用“ Dan的分数”时,它就在记忆中就在那里。我们可以以“ Dan的分数”的名字要求它。

变量的全部要点是它们有所不同。

可能的变量列表:

丹对乒乓球的编码挑战。

最好在上面链接的变量上参考Dan的视频。该书讨论了Java中具有相似性的变量,但由于需要声明变量类型,但仍然会感到困惑。

丹的第一个例子是在屏幕上移动一个圆圈,有一个宝贵的调试课程。他以略有不同的版本一遍又一遍地重复此短语。 “让我们前提是计算机。”或“成为计算机的人”。

我在这里写了示例。即使此代码相当简单,它还是让学生像计算机一样开始思考。逐步思考计算机如何执行代码。这将是至关重要的,因为代码变得更加复杂。

请注意他还如何讨论以下操作:

circleX = circleX + 1

很难将其视为一个分配操作(而不是“等于”),在该操作中,对右侧进行评估然后“分配”到左侧,但这是一个关键的概念。

示例4.3和4.4使用变量改变形状的大小,颜色和位置。

练习4.4,以获取更多变量的练习。

Dan很聪明,让学生首先先用硬编码值绘制这些草图,然后再用变量替换这些值。始终从基础知识开始 - 请确保首先获得基本图形,然后继续使用像新概念之类的更先进的东西。

就像鼠标和鼠标一样 - 这些是与所有草图相关的通常需要的数据(窗口的宽度,按键盘上按键等)

命名自己的变量时,请避免使用系统变量名称。

常用的系统变量:

这是使用系统变量的示例。

我认为这不会被任何编码火车视频所涵盖。请参阅上面的有关MouseX并制作自己的变量的视频。

练习4.5,使形状相对于窗口尺寸调整大小,在线编辑器中不起作用。我尝试了我的代码,并且在学习p5.js存储库中的代码。我认为该代码可能在不推荐使用的P5.JS编辑器中起作用(当启动单独的帆布时,可以调整大小 - 类似于处理的情况),但是在线编辑器不会发生这种情况。

这是我能提出的最好的答案。我使用了窗口宽度和窗户,而不是宽度和高度(书中建议)。

无论如何,这似乎是绕道的好时机。现在,我将通过DAN的WorkFlow视频来查看此代码在本地服务器上的浏览器中是否有效。看看我是否可以执行他的工作流视频中的步骤,这也是一个很好的测试。开始了。

第一注意 - 我也可以尝试Codepen。在此视频之后,我会这样做。丹还提到了小故障。我也会研究一下。

请注意,我使用的是崇高的文本而不是原子,因此我下载了sublimeserver的软件包将崇高变成服务器。我记得我需要先安装软件包控件才能下载诸如Sublimeserver之类的内容。如果您是编程的新手,那么您肯定会陷入此阶段,因为浏览这些设置详细信息是令人困惑的。

Sublimeserver也可以像Dan在Atom中的榜样一样进行重新加载。

这是成功的 - 我什至带有Sublime Text的故障问题软件包管理器。 :)

有几个命令要记住:

p5 generate -b myproject

(node) http-server

python -m SimpleHTTPServer

书籍学习处理中的下一部分是关于使用Random()函数,但是编码列车在此之前有两个视频。一个关于JavaScript对象,另一个关于地图功能。在转到Random()之前,我将遵循编码列车课程并解决这些主题。

DAN设置了使用变量并在屏幕上移动椭圆的示例。

然后,他使用一个对象来组织变量。这为以后的基础设定了基础,使代码更加整洁,并跟踪您的创建内容。

var x = 0;

var y = 100;

var diameter = 50;

//becomes...

var circle = {

x: 0,

y: 100;

diameter: 50

};

这是JavaScript对象表示法。我们可以访问圆圈的数据。

我们使用点表示法访问此数据。

ellipse(circle.x, circle.y, circle.diameter, circle.diameter)

练习是使用对象重新组织我们的代码。这是使用对象的示例4.4。

Dan在此视频中还指出,在编写代码时,我们应该非常习惯于查看错误消息。这是绝对正确的。如何调试这些错误消息是另一个故事...

这个降价文件越来越长。我觉得这需要一张目录。

我可能还可以添加有关Markdown的基础知识的绕道,但我现在会跳过。

我为自己能够在Markdown中创建目录的问题而感到自豪。我可能没有找到最好的方法 - 也许某种JavaScript/node.js工具更有效 - 但是现在我找到了一种有效的方法。那就足够了。

这也是谷歌搜索答案的故障排除,并找到相关的Stackoverflow文章的良好经验。我需要阅读几篇不同的文章,最终,通过将两个文章汇总在一起,我将目录工作表明。

这是我觉得有帮助的Stackoverflow的两篇文章。

此外,这是我的目录中的示例代码:

# Table of contents

[Introduction](#introduction)

- [What is p5.js?](#what-is-p5js)

- [Incremental Development](#incremental-development)

那么,为什么此代码可以工作?

如果您将鼠标悬停在GitHub Markdown文件中的标头上,则会看到出现一个小图标,然后如果您悬停在该图标上,则会在屏幕左下方看到链接本身。该链接的格式是<project URL#<header name> 。

您可以在目录的括号部分中使用该#<header name>链接到连接的标头。您可以将任何文本放在括号中 - 这是在页面上实际显示的文本。

请注意,这些标头名称为“ slugifiend形式”,这意味着它们都在较低的情况下,空间被' - '取代,并且所有标点符号已删除。

For instance, Incremental Development becomes "incremental-development" and What is p5.js? becomes "what-is-p5js".

Just a note to self that I'll have to return to learn more about Git and GitHub.

I foresee this being a potential problem down the road as I develop larger projects.

I just almost got into some issues with git stash . That almost led to a Git rabbit hole, with me resolving Git conflicts that may or may not have existed, with upstream changes that I dont really understand.

I'll leave this on the backburner for now, but I know that this is important, and potentially a major hurdle.

Just to do a quick recap of what I encountered so I don't forget.

I remembered that I run git stash at some point (following along with a Git error message I had received), so I decided to Google git stash to find out what git stash even means.

I then ran a series of commands, including git stash list , git stash apply and git stash show .

It turned out I had a merge conflict in my README.md file.

I tried to resolve the conflict in Sublime, but somehow whatever I was doing wasn't working.

I watched Dan's video on merge conflicts.

I copy and pasted my error message into Google and that didn't help - it just led to the Git rabbit hole (Git rebase?!).

I even ran git reset --hard at one point. I'm not sure if that did anything to help.

Ultimately, upon inspecting the merge conflict itself, it didnt really look like a conflict at all. I couldn't see any changes that I needed to make. So I ran git stash clear which got rid of the stashed away commit. It didn't look like I had stashed anything important.

This ultimately solved the issue.

I don't know if this sort of hack away and try everything approach is ok - maybe it is - but it's a little nerve-wracking.

I remember being told that when learning development, you have to be ok with "breaking things". In this case, I interpreted that to mean, you have to be ok with messing with your code, with the risk that you'll "screw things up", only to have to go back and fix it later. It's scary when you're new to coding and you feel that you don't have to the tools to fix what you've "broken", but I guess you can only develop those tools by "breaking" a lot of things and then trying to put them back together.

See the Carol Dweck TED talk on the growth mindset and this TED radiohour podcast on the Nudge technique for changing habits for more strategies on breaking out of your comfort zone and becoming comfortable with taking risks.

I'm beginning to think that my thoughts on Zen and deliberate practice might stem from being stuck in a fixed mindset. If I can continue to try to see challenges as opportunities, I will maybe be more successful on my coding journey (or maybe just be less frustrated by what I've been considering "setbacks" or "roadblocks").

Also, listen to this freakonomics radio podcast on why you always finish projects late. You may think you can learn to program in six months, or a year, but maybe it will take you thre or four years. There is something called the planning fallacy where we tend to underestimate how long projects will take. This is related to being overly optimistic about our chances of success about the projects we undertake. This is directly related to coding. We think it will take shorter than it actually will to learn to code, and we're overly optimistic about our ability to learn to code in the first place.

Here's Dan's video on the map() function.

Example - as you move the mouse across the screen, background color changes from black (RGB(0)) to white (RGB(255)).

Let's also say the canvas has dimensions of 600 width x 400 height.

So mouseX has a range of 0 to 600. And RGB has a range of 0 to 255. So we have to map the mouseX range to the RGB range. When mouseX = 0, RGB = 0, and when mouseX = 600, RGB = 255.

句法:

col = map(mouseX, 0, 600, 0, 255)

Here's Dan's code using the map function

This example is the same as my variables example, except I use the map function to make the background change from black to white as the the mouse moves from the left side of the canvas to the right.

Here is Dan's video on random().

Think back to incremental development - learn the fundamentals by looking at individual pieces - programs that do one and only one thing. Then begin to add functionality on top, step by step.

random() returns a value - abs() does the same thing - more on this in Chapter 7.

We have learned how to make one circle, at a particular location, with a particular size and fill, using variables.

If we want to make a new circle, with a random size, color, and position, every time through draw(), we can use the random() function.

The random() function in p5.js returns a floating point (or decimal) value. The book and Processing website talk about casting these returned values to integers if you want to return an integer instead of a float.

In JavaScript, I believe you would use a function such as Math.floor() to accomplish the same task.

I just discovered that there's an int() function in p5.js.

Another thing to note from the video - Dan's steps in debugging

Dan's video had a number of good exercise suggestions at the end- here's one:

Here's Dan's dots example. Note that he puts the variables into JavaScript objects.

See also this example, random painting, from the book and Dan's repo, which takes every variable associated with drawing the ellipse (fill, location, size), and assigns it to a random number each cycle through draw().

When reading a book, or watching videos, it's easy to fall into a trap of being told what code is going to do and not having to think about it for yourself.

I am trying to get into the habit of reading the code and thinking through what the code is going to do before running it. I did this with the random painting program.

In the final part of this chapter, we update our original sketches (for Dan this was "Zoog", for me this was "Fido" and the house drawing) to incorporate what we've learned - variables and the random() function. We should even try putting variables into objects, and maybe even using map() to tie everything together.

Here's Dan's "variable Zoog" in p5.js.

Here's my updated "Fido" with two new pieces of functionality:

We can complete Feature 1 for Fido by taking our previous program that used mouseX and mouseY and substituting our own variables in their place. (Dan used the word "simply" here - it may be a knee-jerk reaction but I will never use the word simply when it comes to coding). Remember the article above about the rule of simply.

We can implement Feature 2 by creating variables for the red, green, and blue values to plug into the fill() function.

Start with video 3.1 from Coding train

Taking different paths

Not on using the dist() function for rollovers (might come up in later video)

Brief note on == vs === but said that might come up in videos on strings

Boolean test - true or false (1 or 0)

Boolean expression - evaluates to true or false

Use the current value stored in a variable in boolean expressions (x > 20))

Relational Operators

>, <, >=, <=, ==, !=

Conditionals are another word for boolean expressions

Introduces the concept of branching - depending on various conditions, the program can follow different paths

''' // If the mouse is on the left side of the screen, draw a rect // on the left side of the screen

if (mouseX < width/2) { fill(255); // white rect(0, 0, width/2, height); } '''

Example with else statement:

// If mouse on left, draw white background, otherwise

// draw black background

if (mouseX < width/2) {

background(255);

} else {

background(0);

}

Else if - statements evaluated in order presented. As soon as one is found to be true, code is executed and remaining boolean expressions are ignored

// If mouse on left third, background white,

// if middle, draw gray, otherwise black

if (mouseX < width/3) {

background(255);

} else if (mouseX < 2*width/3) {

background(127);

} else {

background(0);

}

Exercise 5-1: Grading system where numbers are turned into letters (Dan doesn't have an answer - I'll code something placing text on the screen)

I ended up using the Math.floor function and also various text functions from p5.js to display grades on the screen.

I found that I needed to declare the grade variable outside of setup, without an initial value. Then give grade its initial value within setup, then use that value within draw. I think this is a pattern I might need to keep following.

Note this important example from the book about how conditional statements work. Meaning, as soon as one is found to be true, the code is executed and the remaining boolean expressions are ignored:

''' // Determine if a number is between 0 and 25, 26 and 50, or > 50

// good code

var x = 75;

if (x > 50) { print(x + " is greater than 50!"); } else if (x > 25) { print(x + " is greater than 25!") } else { print(x + " is 25 or less!") }

// Output: 75 is greater than 50!

// Bad code

var x = 75;

if (x > 25) { print(x + " is greater than 25!"); } else if (x > 50) { print(x + " is greater than 50!") } else { print(x + " is 25 or less!") }

// Output: 75 is greater than 25!

// first conditional is true, so code executes and rest of // boolean expressions are ignored

'''

Another example:

''' // If a number is 5, change it to 6. If a number is 6, change it to 5.

// good code

var x = 5; print("x is now: " + x); if (x == 5) { x = 6; } else if (x == 6) { x = 5; } print("x is now: " + x)

Output: "x is now: " + 6

// bad code

var x = 5; print("x is now: " + x); if (x == 5) { x = 6; } if (x == 6) { x = 5; } print("x is now: " + x)

Output: "x is now: " + 5

// This is buggy because both if statements are executed '''

Our program will perform different tasks based on the result of different conditions

Heres the pseudocode:

Note that functions are often included in libraries because they solve common problems. The constrain() function can be used to "constrain" the size or location of a shape, so that it does not get too big or small, or wander off of the screen.

Functions like constrain are also a great way to avoid errors and to ensure that sections of code work well together on larger projects with multiple programmers.

A more advanced example will change all three color components according to mouse location and click state (mouseIsPressed - mousePressed in processing is mouseIsPressed in p5.js). Note that the system variable mouseIsPressed() is true or false depending on wheter the user is holding down the mouse button.

These examples demonstrate using the constrain() function

Example: If the mouse is on the right side of the screen AND the mouse is on the bottom of the screen, draw a rect in the bottom right corner.

if (mouseX > width/2 && mouseY > height/2) {

fill(255);

rect(width/2, height/2, width/2, height/2);

}

Logical Operators:

&& (logical AND)

|| (logical OR)

! (logical NOT)

Example using logical NOT: if (!mouseIsPressed) { ellipse(width/2, height/2, 100, 100); } else { rect (width/2, height/2, 100, 100); }

The above example could also be written without the logical NOT, saying:

Exercise demonstrating a simple rollover using dist.

伪代码:

So - how do we know if the mouse is in a given corner?

The answer uses numerical values (100 for mouseX and mouseY). I am going to use width and height.

Exercise 5.6: squares fade from black to white when the mouse leaves their area

Making a button - a rollover that responds when clicked

Practicing learning how to program these GUI elements from scratch (bottons, rollovers, sliders) is an excellent way to learn the basics of variables and conditionals. It also allows you to create customizable interfaces.

Boolean variables to program a button. Boolean variables can only be true or false.

Our button example starts with one booleann variable with a starting value of false (button starts in the off state).

var button = false

Our sketch will turn the background white when the button is pressed, and black when it is not.

if (button) {

background(255);

} else {

background(0);

}

We need to combine with with checking mouse location to see if it's inside of a shape (in our example a rectangle). If it is inside the rectangle, and the mouseIsPressed, we set the button variable to true or false accordingly.

See this example.

Let's make this more like a light switch.按下按钮。 If the light is off, it turns on. If it is on, it turns off. ("toggles the switch")

We need to use the mousePressed() function here. By definition, when the user clicks the mouse, the code inside mousePressed() is executed once and only once.

mouseIsPressed is used when you check if the mouse is being held down.

Watch Dan's video for an example of creating a button. He does a very nice job of explaining all the steps of creating the button.

The example code from Coding train is better in my opinion than the p5.js ported code. Here's my version Note also that Dan mentions that we could use a function to determine if the mouse is inside of the rectangle.我们稍后再解决。

Exercise 5.8 modifies the circle move program to incorporate mousePressed(). The book only asks to make the circle move when the mouse is pressed, but I updated it so the circle stops when the mouse is pressed as well.

We can use conditionals to check if a shape (or something more complex like Zoog or Fido) has reached the edge of the screen, and if so make it turn around.

Write a program where a simple circle moves across the screen horizontally from left to right. When it reaches the right edge of the screen, it reverses direction.

We need to introduce a new variable - var speed = 1

To make the circle move, the value of the x location should change each cycle through draw() - x = x + speed .

This would make the circle run off the edge of the screen.

To make it turn around, we need a conditional statement:

if (x > width) {

speed = speed * -1

}

To make the circle bounce off of both sides of the screen, we can use the conditional OR:

if ((x > width) || (x < 0)) {

speed = speed * -1

}

See example 5.6 for the bouncing ball.

This exercise modifies the above example to have the ball bounce off all the edges.

I was inspired by this repo about brickbreaker.

The bouncing ball logic of incrementing and decrementing a variable can be aplied to also, say, make a color more red.

See this example called "bouncing color".

Now for more complex motion - a rectangle that follows the edges of the window.

We can think of a rectangle's motion as having four possible states, numbered 0 through 3:

We use a variable to keep track of the state number and adjust the x,y coordinate of the rect according to the state. For instance, if the state is 2, x = x - 1.

Once the rect reaches the endpoint for that state, we can change the state variable. If state is 2, x = x - 1. If x < 0, state = 3.

This is probably the most complicated program we've written so far.

Coding gravity with conditionals.

Gravity is a force of attraction between all masses.

Adding "acceleration" to our bouncing ball, which increases or decreases speed. Acceleration is the rate of change of speed. And speed is the rate of change of location.

speed = speed + acceleration

See this simple gravity example. I updated it adding code so the ball bounces off the edges.

We will learn:

A generative process of repeating a set of rules or steps over and over again.

It is a control structure . It is similar to conditionals (if/else), except instead of asking a yes or no to determine if a block of code should be executed one time , it asks a yes or no question to determing how many times the block of code should be repeated .

There are three types of loops:

The only loop you really ever need is a while loop, though the for loop is a convenient alternative for simple counting operations.

Do-while is rarely used so there are no examples for it.

While loops employ a boolean test condition. If the test evaluates to true, the instructions enclosed in curly brackets are executed. If false, we continue on to the next line of code.

See these two examples using while loops to draw lines and ellipses.

You don't want infinite loops - where the boolean test condition is always true.

To avoid an infinite loop, we must make sure that the exit condition for a loop will eventually be met.

If you have an infinite loop, force quit the program.

Dan has a kind of confusing example of an infinite loop and how to avoid it using constrain. Maybe his videos are clearer.

A style of while loop whereone value is incremented repeatedly (often useful with arrays).

Example code:

// Start at 0 and count up to 9

for (var i = 0; i < 10; i++)

// Start at 0 and count up to 100

for (var i = 0; i < 101; i += 10)

// Start at 100 and count down to 0 by 5

for (var i = 100; i >= 0; i -= 5)

For loops consist of three parts:

Here's rewriting the earlier lines and ellipses exercises using for loops.

Some very cool examples of using loops to create funky drawings. I could never create these, but this is a good example of trying to read code then guess what it displays. Good to see what's possible with loops and code.

界。 Funky rects. Progressively darker squares. This darker squares one gives a cool optical illusion that the squares are different sizes but they aren't. Spaced squares.

Local vs. Global variables

Deciding what it means to declare a variable somewhere other than the top (before setup()) and how to go about choosing the right location for declaring a variable.

Scope - some variable exist (and are accessible) throughout the entire program's life (global scope) and some live temporarily, only for the brief moment when their value is required for an instruction or calculation (local variables).

Global variables are declared at the top of the program - outside of setup() and draw(). They can be used in any line of code anywhere in the program.

Local variables are variables delared within a block of code. These variables are only available for use within that specific block of code where it was declared (is this the same in JavaScript - I'll have to check in on this - it's not). Dan has a video on scope in his Processing series, but not on scope related to JavaScript.

See this video on let vs var (and even const) and this article which discuss function and block scope for variables in JavaScript and the concept of hoisting.

Display doesn't update until the end of draw() is reached. This is critical to remember when using while and for loops. These loops serve the purpose of repeating something in the context of one cycle through draw(). They are a loop inside of the sketch's main loop, draw().

To display one line at a time, we need a global variable in combination with the very looping nature of draw() itself.

See this example where lines display, one at a time, from y = 0 until y = height.

The next exercise is tricky. It implements the above example but using a for loop.

Using the loop inside draw() for interactivity. This code displays a series of rectangles, from left to right, each colored with a brightness according to its distance from the mouse.

We can use the same principles to draw multiple arms for Zoog. Or draw multiple instances of Zoog by placing the code for Zoog's body inside of a for loop.

Exercise 6.8 asks you to create a grid of squares using a for loop - actually using nested loops. Here's Dan's video on nested loops. It's a pretty big oversight that the book doesn't explain nested loops, because they can be pretty complicated to understand. A better example is actually a checkerboard. It introduces the modulo / remainder operator. My example draws a checkerboard. Mehran from Stanford also uses a checkerboard in his CS106A class.

Step 1: Rewrite lesson one design with variables instead of hard-coded values. Use a for loop for something.

Step 2: Use assignment operations that alter the values of those variables and make the design dynamic.

Step 3: Using conditional statements, alter the design behavior based on certain conditions.

I wanted to do something beyond my skill level - go from a daytime sky to a night time sky and back. I could sort of do it - I went from light blue to dark blue sky, but then it got way too complicated. I'll stick with a "simpler task" - putting lines on the house which serva as a design. And updating orion with begin and endshape.

概述:

I'm sure there are many differences between Java and JS functions - I'll need to revisit this - watch Dan's videos and probably read about it

Functions are a means of taking the parts of our program and separating them out into modular pieces, making our code easier to read and revise

Returning to Space Invaders - steps inside draw():

Previously, we would have translated the above pseudocode into actual code, and placed it inside draw().

Now, we can approach the problem as follows:

// calling functions we made up inside of draw - also called top-down design

// Stanford 106A is really good for an overview of top-down design

function draw() {

background(0);

drawSpaceShip();

drawEnemies();

moveShip();

moveEnemies();

}

What about function definitions? We'll get to this later

Why is it so important to write our own functions?

Local and global variables are also important, as functions are independent blocks of code that will require using local variables (I think this is true in JavaScript - function scope?)

This just means moving beyond the functions provided by p5.js (like line()) and writing our own functions.

A function definition ('declaration') had three parts:

Function example:

function drawBlackCircle() {

fill(0);

ellipse(50, 50, 20, 20);

}

This code won't happen unless it's called from a part of the program that is being executed. We accomplish this by referencing the function name (calling the function).

function draw() {

background(255);

drawBlackCircle();

}

The exercise is to write a function that displays Zoog, or my own design using a function.

Here's Dan's first video on functions.

His example in the video is a bouncing ball, demonstrating modularity.

Here is the bouncing ball code with functions.

Another benefit of functions is greater ease in debugging - we can turn on and off parts of the program by commenting out certain functions

Debugging tip

By adding function calls one by one and executing the sketch each time, we can more easily deduce the location of the problem code

AKA Parameters - values that are passed into a functions

Instead of just saying move - you're saying move n steps (n is the argument)

例子:

// diameter is an argument to the function

// drawBlackCircle()

function drawBlackCircle(diameter) {

fill(0);

ellipse(50, 50, diameter, diameter)

}

An argument is simply a variable declaration inside the parens in the function definition

This variable is a local variable to be used in that function.

Another example:

// The argument 'speedFactor' affects how fast

// the circle moves

function move(speedFactor) {

x = x + (speed * speedFactor)

}

So, to move the ball twice as fast: move(2)

Or pass in a variable or the result of a mathematical expression: move(mouseX/10)

Arguments allow for more flexible, reusable functions.

Let's look at the code for drawing a collection of shapes and examine how functions allow us to draw multiple versions of the pattern without retyping the same code over and over.

The example will be drawing a car. We'll look at two examples - one using functions, one without.

The example from the book for car without functions doesnt match up perfectly because he doesn't even show if the code for the cars is in setup() or draw(). Maybe he isn't using setup() or draw() because he doesn't need to in a Processing sketch?

Here's car with functions.

The book example doesn't work because of variable scope.

I actually logged an issue about this example because I thought that the example was buggy. I asked them to include something about hoisting in JavaScript. I'll see if I get a response.

Note the use of color() in this example on parameter passing in functions.

Parameter passing is a very important idea.

The value you pass as a parameter to a function can be a literal value (20, 5, 4.3), a variable (x, y), or the result of an expression (8 + 3, 4 * x/2, random(0, 10))

Arguments act as local variables to a function and are only accessible.

Exercise 7.4: Write code that calls a function

The code is a function that adds three numbers and prints the sum of the three.

Exercise 7.5- write a function definition: You are provided with the function call multiply(5.2, 9.0) . Write the code that takes these two parameters, multiplies them and prints the result to the message window.

Exercise 7.6 is interesting because it's a bouncing car. Using functions, global, and local variables altogether.

This may or may not be the same in JavaScript. I'll need to read more.

In Java, whenever you pass a primitive value (integer, float, char) to a function, you do not actually pass the value itself, but a copy of that variable.

Here is a function called randomizer(). This function receives one argument (float) and adds a random number between -2 and 2 to it.

Pseudocode for randomizer():

Let's see if the same thing happens in JavaScript. (Yes it is because JavaScript is pass by value for primitives.)

Here's the randomizer() code.

This is commonly referred to as "pass by value".

Remember this article later because it describes how JavaScript uses pass by value for primitives but call by sharing for objects.

This definitely gets confusing.

Flow of a program when using a function. The code is executed in the order that the lines are written, but when a function is called, the code leaves its current line, executes the lines inside the function, then comes back to where it left off.

这是一个例子:

An interesting example to predict the output of the program that has various function calls. You have to understand the flow of functions and function calls.

Here's the code.

This is not really relevant to JavaScript - JavaScript is untyped - not totally clear on how and why this matters.

But return values are definitely important.

As soon as the return statement is executed, the program exits the function and sends the returned value back to the location in the code where the function was called. That value can be used in an assignment operation (to give another variable a value) or in any appropriate expression.

示例:

function sum(a, b, c) {

var total = a + b + c;

return total;

}

var answer = sum(5, 10, 32);

var x = sum(5, 6, 8);

var y = sum(8, 9, 10) * 2;

var z = sum(x, y, 40);

line(100, 100, 110, sum(x, y, z));

Functions that return values are traditionally used to perform complex calculations that may need to be performed multiple times throughout the course of the program (like calculating the distance between two points (x1,y1 and x2,y2)).

The dist() function is built into p5.js to calculate the distance between pixels: var d = dist(100, 100, mouseX, mouseY)

This calculates the distance between (100, 100) and (mouseX, mouseY). Without this function, we would need the Pythagorean Theorem.

Our version of p5.js dist() function:

function distance(x1, y1, x2, y2) {

var dx = x1 - x2;

var dy = y1 - y2;

var d = sqrt(dx*dx + dy*dy);

return d;

}

Example 7.4: Using our distance function to calculate brightness for squares in quadrants.

Exercise 7.8: write a function that takes one argument (F for Fahrenheit) and computes the temperature in Celsius.

Two new functions - drawZoog() and jiggleZoog() - move randomly in x and y directions.

Incorporate arguments so jiggliness is determined by mouseX position and Zoog's eye color is determined by Zoog's distance to the mouse.

Example 7.5 - Zoog with functions.

Exercise 7.9 - Multiple Zoogs - calls a function to draw Zoog within a for loop, so multiple Zoogs are drawn.

In this chapter:

We talked about JavaScript Objects earlier.

Dan's first video is introduction to OOP with ES6.

He then talks about ES6 Classes.

There could be significant differences between OOP in Java and JavaScript.我想我们会看到的。

We're not introducting any new programming fundamentals - objects use everything we have already learned (variables, conditionals, loops, functions).

What is new is a different way of thinking, a way of structuring and organizing everything we have already learned.

A program for your day (a list of instructions):

What is involved here? What things are involved?

The maint thing is you - a human being. You exhibit certain properties. You have certain traits (how you look). You can do things (wake up, eat, drive).

An object is like you - a thing that has properties and can do stuff.

The properties of an object are variables and the stuff an object can do are functions. OOP is the marriage of everything we have learned up to now (data and functionality) all rolled into one thing .

Data and functionality for very simple human object.

数据:

功能:

Of course, this is not a real human. This is just the idea, or concept behind a human. It describes what it is to be a human. This is a template known as a class . A class is different from an object. You then create instances of a class - which are individual human beings.

How is using objects in our main program (setup() and draw()) useful?

Car example:

Data (global variables):

设置:

画:

What did we do previously:

With OOP, we an take the variables and functions out of the main program and store them inside the car object .

A car object will know about its data - color, location, speed. That is part one.

Part two is the stuff it can do - the methods (functions inside an object). The car can move and it can be displayed .

Pseudocode for object-oriented design :

Data (Global Variables):

设置:

画:

We now have only one variabe - a car variable - instead f separate variables for car color, location, and speed.

Instead of initializing those three variables, we initialize one thing - the Car object.

Those variables (color, location, speed) still exist, but they live inside the Car object. They will be defined in the Car class.

There's now code for a Java class - I'm watching the Coding Train video to see if the code is the same.

Here's the code from the coding train video.

Note that his code uses JavaScript let, instead of var.

The examples online for 8.1 for learning p5.js put functions into the object literal. Dan seems to like constructor functions. Here's example 8.1 using a constructor function.

Use of objects in p5.js makes for clean, readable code.

The hard work goes into writing the template - writing the class itself.

It's a good exercise to take a program without objects and, not changing the functionality at all, reqrite it using objects.

All classes must include four elements:

Here's a simple non-OOP car:

let c;

let xpos;

let ypos;

let xpseed;

function setup() {

createCanvas(200, 200);

c = color(255);

xpos = width/2;

ypos = height/2;

xspeed = 1;

}

function draw() {

background(0);

display();

drive();

}

function display() {

rectMode(CENTER);

fill(c);

rect(xpos, ypos, 20, 10);

}

function drive() {

xpos += xspeed;

if (xpos > width) {

xpos = 0;

}

}

Here's the program above placed into a Car class:

''' // Declare car object as a global variable let car;

function setup() { createCanvas(200, 200); // Initialize Car object car = new Car(); }

function draw() { background(0); // Operate Car object car.display(); car.drive(); }

class Car { constructor(c, xpos, ypos, xspeed) { this.c = color(255); this.xpos = width/2; this.ypos = height/2; this.xspeed = 1; }

// Functionality

display() {

rectMode(CENTER);

fill(this.c);

rect(this.xpos, this.ypos, 20, 10);

}

drive() {

this.xpos += this.xspeed;

if (this.xpos > width) {

this.xpos = 0;

}

}

} '''

The Class Name - "class WhateverNameYouChoose".

Data - a collection of variables. Often referred to as instance variables, since instance of an object contains this set of variables.

Constructor - Special function inside of a class that creates the instance of the object itself. Where you give instructions on how to set up the object. Called by invoking the new operator - "car = new Car()".

Functionality - Add functionality by writing methods.

The three steps outlining how to use an object in a sketch: 1: Declare an object let car 2: Initialize an object (in setup()) car = new Car() 3: Call methods on the object (in draw()) car.move()

Let's look at the details behind these three steps.

Step one: Declaring an object variable

In JavaScript we don't need to specify a type. We do need to give our variable a name.

Objects are complex data types (as opposed to primitive data types like ints, floats, and chars). This is because they store multiple pieces of information: data and functionality. Primitives only store data.

Step two: Initializing an object

We initialized a variable using an assignment operation: let x = 10 .

Initializing an object is a bit more complex. Instead of simply assigning it a primitive value, like an int or a float, we have to construct the object. An object is made with the new operator. car = new Car();

"car" is the object variable name and "=" indicates that we are setting it equal to something that something being a new instance of a Car object. What we are really doing here is intializing a Car object. This line of code calls the constructor , which we create later (simply called "constructor"), that initializes all of the objects variables and makes sure the Car is ready to go.

Beware of "NullPointerException" .

It looks like in Java, the default value of a primitive int is 0, while the default value of a variable in JavaScript is undefined.

If you forget to initialize an object, you get the value null, meaning nothing.

Apparently, in JavaScript, the error will be "undefined is not a function".

Step 3: Using an object

Once we have successfully declared and initialized an object variable, we can use it.

Using an object involves coalling functions that are built into that object.

Functions that are inside of an object are called "methods" in Java - I'll call them the same for now in JavaScript.

Calling a method inside of an object is accomplished via dot syntax. variableName.objectMethod(Method Arguments)

Example: - car.draw() - car.display()

Dan actually calls this "Putthing it together with a Tab ". I'm going to assume there's some other construct in JavaScript besides a Tab because I don't know what a Tab is.

Here is Example 8.1 - a Car class and a Car object. Note that I submitted this to Dan's repo as a pull request and haven't heard anything yet.

We placed the Car class below the main body of the program (under draw()), which is identical to where we have been placing user-defined functions. But technically speaking the order does not matter as long as the blocks of code remain intact.

It's just nice to have things make the most logical sense to us humans, the bottom of the code being a good starting point.

Processing offers a useful means for separating code fro each other through the use of tabs.

We're not using Processing, however. Let's consult the videos.

It doesn't look like he talks about some analogous concept to tabs in the videos.

I think in JS you would just create new files for each class. For now I'll just assume each tab is a new .js file.

You can name each tab anything you like, but you should name it after the class you intend to put there.

You can then type the main body of code on one tab (entitled "objectExample") and type the code for your class in another (entitled "Car").

I'm assuming these will be sketch.js and car.js...

So basically, create a new file calles "objectName".js to hold the code for your class.

Let's try this with our Car example from before.

Apparently my assumptions about a new .js file were wrong. I got led down a rabbit hole about class-based vs. prototype-based languages.

This might be a bit over my head for now.

Note also that classes are "syntactical sugar" over JavaScript's prototype-based inheritance model.

I'm going to need a real textbook to better understand this concept.

Wow - it actually works...

All I needed to do was reference the car.js file in index.html....

That's a big lesson. All the reading and searching, no answers, and all I needed to do was add one line to index.html. All the other reading and researching was helpful I guess, but ultimately not getting me any closer to the answer.

Our old code would have create identical objects.

If we want to create different objects, we need constructor arguments.

For instance: var car = new Car(color(255, 0, 0), 0, 100, 2)

We need to rewrite the constructor to reflect this:

constructor(tempC, tempXpos, tempYpos, tempXspeed) {

// The Constructor is defined with arguments.

this.c = tempC;

this.xpos = tempXpos;

this.ypos = tempYpos;

this.xspeed = tempXspeed;

}

Arguments are local variables used inside the body of a function that get filled with values when the function is called.

We are now creating temporary constructor artyments that exist solely to pass a value from where the object is made into the object itself.

This allows us to make a variety of objects using the same constructor .

Here's the program updated with constructor arguments, so there are now two car objects, each different.

The next exercise is to rewrite the gravity example using objects with a Ball class. Include two instances of a Ball object.

You can include as many classes as you feel like writing.

Back to Space Invaders. You could include a:

Using an object for each entity in your game

Although not primitive, classes are data types just like ints and floats. Since classes are made up of data, an object can therefore contain other objects!

This could be different in JavaScript since it's a prototype language instead of a class-based language, as described above. I won't get too into this.

Objects can be passes as arguments ito a function. Again I'm sure JS has all sorts of different issues here, left for another time.

Here, Dan discusses pass by copy for primitives vs pass by reference for objects. With pass by reference, if an object is passed to a function, those changes will affect that object used anywhere else in the sketch.

Again, this is likely different for JS.

This could start to get tricky because the book will start to use multiple objects, pass objects into functions, etc.

I might need a real JavaScript book to figure out how to use JavaScript classes and objects sadly.

我们看看。

So, when do we use object-oriented programming?

总是!

Objets allow us to organize concepts inside of a software application into modular, reusable packages.

However, it's not always convenient or necessary to start out every project using object-orientation, especially when you are learning.

We can easily "sketch" out vidual ideas with p5.js using non object-oriented code.

For any project, take a step-by-step approach. Do not start out writing classes for everything you want to do.

Sketch out your idea first by writing code in setup() and draw(). Nail down the logic of what you want to do as well as how you wnat it to look.

As your project begins to grow, take time to reorganize your code, perhaps first with functions, then with objects.

It is perfectly acceptable to dedicate a significant chunk of your time to this reorganization process (often referred to as refactoring) without making any changes to the end result, that is what your sketch looks like and does on screen.

We will now refactor Zoog by making Zoog into an object. This will give us a leg up in programming Zoog's future life in more complex sketches.

So, let's make a Zoog class.

Exercise 8-6 - rewrite Zoog class to inclood two Zoogs. Vary appearance somehow. Vary behavior somehow. Add color variable.

Take your lesson two project and reorganize your code using functions.

Reorgainze the code one step further using a class and object variable.

Add arguments to the Constructor of your class and try making two or three objects with different variables.

Here's my lesson 3 project - Sol Lewitt Squares. One version with functions, one with classes.

In this chapter:

What if we want a program with 100 car objects?

We could use clever copying and pasting, but that's not a good solution.

An array is one thing tht contains a list of variables.

Any time a program requires multiple instances of similar data, it might be time to use an array.

示例:

A variable is a named pointer to a location in memory where data is stored. In other words, variables allow programs to keep track of information over a period of time.

An array is exactly the same, only instead of pointing to one singular piece of information, an array points to multiple pieces.

We an think of an array as a list of variables.

A list is useful for two important reasons. One, it keeps track of the tlements in the list itself. Two, the list keeps track of the order of those elements. The order can be just as important as the information itself.

In an array, each element of the list has a unique indes, an integer value that designates its position in the list. In all cases, the name of the array refers to the list as a whole, while each element is accessed via its position.

We start counting arrays from index 0. This is because the first element of the array is located at the start, a distance of zero from the beginning. Numbering the elements starting at 0 also makes many array operations (the process of executing a line of code for every element of the list) a great deal more convenient.

This is different in Java and JavaScript.

We denote the use of an array by placing empty square brackets ("[]")after the name.

I don't think there's any difference between an array of ints and an array of objects in JavaScript.

Arrays in Java are also of fixed size. Arrays in JavaScript are not fixed size.

You can also use the new keyword to create arrays in JavaScript instead of creating an array literal.

One way to fill an array is to hard-code the values in each spot.

Do we need to initialize an array in JS?大概吧。

What we really want to do is iterate through the elements of the array. This requires a loop.

Consider the following problem:

(A) Create an array of 1,000 floating point numbers. (B) Initialize every element of that array with a random number between 0 and 10.

Part A we already know how to do.

float [] values = new float [ 1000 ] let values = new Array ( 1000 )We want to avoid this for B:

values[0] = random(0, 10); values[1] = random(0, 10); ETC...

Let's describe in English what we want to program (write some pseudocode):

For every number n from 0 to 999, initialize the nth element stored in the array as a random value between 0 and 10.

Translating into code, we have:

let n = 0;

values[n] = random(0, 10);

values[n + 1] = random(0, 10);

etc...

We have not improved the situation, but we have taken a big step forward in understanding th problem. By using a variable (n) to describe an index in the array, we can now employ a while loop or a for loop to initialize every n element.

/// while loop

let n = 0;

while (n < 1000) {

values[n] = random(0, 10);

n = n + 1;

}

// for loop

for(let n = 0; n < 1000; n++) {

values[n] = random(0, 10);

}

We don't want to use hard-coded values like 1000. What if we wanted to use 2000?

We can use array.length.

''' for (let i = 0; i < values.length; i + + ) { values[i] = 0; } '''

Exercise 9-6: Write code to perform the following array operations: 1: Square each number 2: Add a random number between zero and 10 to each number 3: Add to each number the numbe that follows in the array (skip the last value in th array) 4: Calculate the sum of all the numbers

Note this video series on ES6 Array functions like the arrow function, map, fill, reduce, filter, etc.

I'll try to do these exercises with the ES6 Array functions as well.

let nums = [5, 4, 2, 7, 6, 8, 5, 2, 8, 14]

// Square each number

for(let i = 0; i < nums.length; i++){

nums[i] = nums[i] * nums[i]

}

One example to use is the for...of loop.

for (let bubble of bubbles) {

bubble.move();

bubble.show()

}

You need higher order functions for most of these exercises. Dan briefly discusses the difference between functional and object oriented programming (something beyond my scope right now).

Function that takes a function as input or returns a function as output - higher order function.

Can manipulate array in one fell swoop.

Map() might look nice but also might not be high performance (need to replicate entire array).

// Using higher order function map()

function squared(x) {

return x * x;

}

nums = nums.map(squared)

Or with an anonymous function:

nums = nums.map(function(x) {

return x * x;

});

Now with an arrow function:

nums = nums.map(x => x * x);

2: Add a random number

nums = nums.map(x => x + Math.floor(Math.random() * 10));

3: Add to each number the number that follows (skip last value)

// without higher order functions

for(let i = 0; i < nums.length - 1; i++) {

nums[i] += nums[i + 1]

}

4: Find sum

// Without higher order functions (reduce())

let sum = 0;

for (let num of nums) {

sum += num;

}

function sum(acc, num) {

console.log(acc);

return acc + num;

}

// acc is like sum in previous example

let answer = nums.reduce(sum, 0);

// pass in initial value otherwise first value of acc is first value of array

Now with arrow syntax:

let sum = nums.reduce((acc, num) => acc + num, 0);

Finding min and max:

function findMax(acc, val) {

if(val > acc) {

acc = val;

}

return acc;

}

let biggest = vals.reduce(findMax);

console.log(biggest);

Making it an arrow function:

let biggest = vals.reduce((acc, val) => {

if (val > acc) {

add = val;

}

return acc;

})

Or using a ternary operator:

let biggest = vals.reduce((a, b) => b > a ? b : a);

Here's the task - programming a train following the mouse - it's not so easy.

It will require an array which will serve to store the history of mouse locations.

We will use two arrays, one to store horizontal mouse locations, and one for vertical.

Let's say, arbitrarily that we want to store the last 50 mouse locations.

First, we declare two arrays:

let xpos = new Array(50);

let ypos = new Array(50);

In setup(), we need to initialize the arrays. At the start of the program there has not been any mouse movement, so we fill the arrays with 0's.

for(let i = 0; i < xpos.length; i++) {

xpos[i] = 0;

ypos[i] = 0;

}

Another way to do this, in one line is:

let xpos = new Array(50).fill(0);

let ypos = new Array(50).fill(0);

Each time through the draw() loop, we want to update the array with the current mouse location. Let's choose to put the current mouse location in the last spot of the array. The length of the array is 50, meaning the index values range from 0 - 49. The las tspot is 49 (length - 1).

xpos[xpos.length-1] = mouseX;

ypos[ypos.length-1] = mouseY;

Now comes the hard part - we want to keep only the last 50 mouse locations.

By storing the current mouse location at the end, we are overwriting what was previously stored there. If the mouse is at (10,10) during one frame, and (15,15) during another, we want to put (10,10) in the second to last spot and (15,15) in the last spot.

The solution is to shift all the elements of the array down one spot before updating the current location.

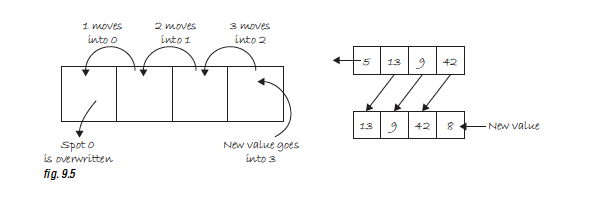

The image below shows how it works.

Element index 49 moves into 48, 48 to 47, etc.

We can do this by looping through the array and setting each element at i to the value of element i plus one .

We must stop at the second to last value because there is no element 50 (49 plus 1).

Instead of i < xpos.length; we must say i < xpos.length - 1 .

Here's the full code for the array shift:

for(let i = 0; i < xpos.length - 1; i++) {

xpos[i] = xpos[i+1];

ypos[i] = ypos[i+1];

}

Finally, we can use the history of mouse locations to draw a series of circles. For each element of the xpos array and ypos array, draw an ellipse at the corresponding values stored in the array.

for(let i = 0; i < xpos.length; i++) {

noStroke();

fill(255);

ellipse(xpos[i], ypos[i], 32, 32);

}

We could make this fancier by linking the brightness of the circle to the location in the array, meaning the earlier (older) values will be bright and small and the later (newer) values will be darker and bigger.

This is accomplished by using the counting variable i to evaluate color and size.

for(let i = 0; i < xpos.length; i++){

noStroke();

fill(255 - i*5);

ellipse(xpos[i], ypos[i], i, 0);

}

Here's the complete code for the snake following the mouse.

The next exercise is to make the snake example object-oriented. We can try to make snakes with slightly different looks (different shapes, colors, and sizes).

I actually needed to look at the Processing example for help.

An advanced problem is to create a Point class that stores the x and y coordinate as part of the sketch. Each snake object will have an array of Point objects, instead of two separate arrays of x and y values.

The next section is about an array of objects, so maybe I'll come back to this later after learning about arrays of objects.

Note here's Dan's example using a point object literal and the splice array function to solve the snake problem.

How can we write a program with 100 car objects?

With OOP and arrays, we can simply transition a program from one object to 10 to 10,000, maybe without changing the car class at all. The class does not care how many objects are made from it.

Revisiting the code for creating one Car object:

let myCar;

function setup() {

myCar = new Car(color(255, 0, 0), 0, 100, 2);

}

function draw() {

background(255);

myCar.move();

myCar.display();

}

Three steps in the above code needed to alter each one to account for an array.

Before we had to:

1: Declare the Car - let myCar; 2: Initialize the Car = myCar = new Car(color(255, 0, 0), 0, 100, 2); 3: Run the Car by Calling Methods:

myCar.move();

myCar.display();

After: 1: Declare the Car Array: let cars = new Array(100); 2: Initialize each element of the Car Array:

for(let i = 0; i < cars.length; i++) {

cars[i] = new Car(color(i*2), 0, i*2, i)

}

3: Run each element of the Car Array:

for(let i = 0; i < cars.length; i++) {

cars[i].move();

cars[i].display;

}

See this example for 100 cars. If we wand to change the number of cars present, all we have to do is change the array definition - nothing else has to change!

Back to the simple rollover effect. A rectangle appears in the window and is one color when the mouse is on top and another color when the mouse is not.

The following is an example that takes this simple idea and puts it into a "Stripe" object. Even though there 10 stripes, each one individually responds to the mouse by having its own rollover() function.

function rollover(mx, my) {

if (mx > this.x && mx < this.x + this.w) {

mouse = true;

} else {

mouse = false;

}

}

This function checks to see if a point (mx, my) is located within a verticle stripe. Is it greater than the left edge and less than the right edge? If so, a boolean variable "mouse" is set to true.

When designing your classes, it is often convenient to use a boolean variable to keep track of properties of an object that resemble a switch. For example, a Car object could be running or not running. Zoog could be happy or not happy.

This boolean variable is used in a conditional statement inside of the Stripe object's display() function to determine the Stripe's color.

function display() {

if (mouse) {

fill(255);

} else {

fill(255, 100);

}

noStroke();

rect(this.x, 0, this.w, height);

}

When we call the rollover() function on that object, we can then pass in mouseX and mouseY as the arguments.

stripes[i].rollover(mouseX, mouseY);

Even though we could have accessed mouseX and mouseY direcedly inside of the rollover() function, it is better to use arguments. This allows for greater flexibility. The Stripe object can check and determine if any x,y coordinate is contained within its rectangle. Perhaps later, we will want the Stripe to turn white when another object, rather than the mouse, is over it.

Here is the full "interactive stripes" example.

Here's an exercise making clickable buttons using classes. It's also good practice in using boolean variables.

p5.js ofers a set of array functions that manipulate the size of an array. I'm not sure how useful this is (unlike in Java where maybe it's more useful with Array and ArrayList), but it's still good to know I guess.

The p5.js Array functions are:

Find more details in the reference.

Here's an example using append() to expand the size of an array. Append is very similar to Array.push() - adding elements to the end of an array.

The example starts with an array of one object. Each time the mouse is pressed, a new object is created and appended to the end of the original array.

From one Zoog object to many. Similar to how we geerated the Car array or Stripe array, we can copy the exact Zoog class created in Example 8-3 and implement an array.

See this example for 200 Zoog objects in an array.

Step 1: Take the Class you made in Lesson Three and make an array of objects from that class

Step 2: Can you make the objects react to the mouse? Try using the dist() function to determine the object's proximity to the mouse. For example, could you make each object jiggle more the closer it is to the mouse?

How many objects can you make before the sketch runs too slow?

I went back to my work from lesson 2 - Fido. First I created a Fido class.

Then I made a number of Fidos using an Array, and when you click each Fido, the color of its nose changes from black to white.

Remember 'Lather.冲洗。重复。'?

What did we learn from Zoog/Fido?

We need to pause now and consider how we can apply what we have learned to what we want to do .

What is our idea and how can variables, conditionals, loops, function, objects, and arrays help us?

Our earlier examples were "one feature" - Zoog would jiggle and only jiggle. Zoog didn't suddenly start hopping. Zoog was also usually all alone. He would never start interacting with other alien creatures along the way.

In the real world, software projects usually involve many moving parts. This chapter aims to demonstrate how a larger project is created out of many smaller "one feature" programs just like the ones we are starting to feel comfortable making.

You, the programmer, will start with an overall vision, but you must learn how to break it down into invidual parts to successfully execute that vision.

We will start with an idea. Ideally, we sould pick a sample 'idea' that could set the basis for any project you want to create after reading this. Sadly there is no such thing. There are unlimited possibilities in programming, but that also means you need to find your own way to creating those possibilities.

Nevertheless, we are going to develop one example that will hopefully serve us welll for learning about the process of developing larger projects.

Our choice will be a simple game with interactivity, multipic objects, and a goal. The focus will not be on good game design, but rather on good software design . How doyou go from thought to code? How do you implement your own algorithm to realize your ideas? We will see how a larger project divides into four mini-projects and attack them one by one, ultimately bringing all parts together to execute the original idea.

We will continue to emphasize OOP, and each of these parts will be developed using a class . The payoff will be seeing how easy it then is to create the final program by bringing the self-contained, fully functional classes together.

Before we get to the idea and its parts, let's review the concept of an algorithm .

Our process:

- 1: Idea - start with an idea

- 2: Parts - break the idea down into smaller parts

- Algorithm pseudocode - for each part, work out the algorithm for that part in pseudocode

- Algorithm code - Implement that algorithm with code

- Objects - Take the data and functionality associated with that algorithm and build it into a class

- 3: Integration - Take all the classes from Step 2 and integrate them into one larger algorithm

An algorithm is a procedure or formula for solving a problem.

In computer programming, an algorithm is a sequence of steps requred to perform a task. Every single example so far in this book involved an algorithm.

An algorithm is not too far from a recipe: 1: Preheat oven fo 400F 2: Place four boneless chicken breasts in baking dish 3: Spread mustard evenly over chicken 4: Bake at 400F for 30 mins

The above is a nice algorithm for cooking mustard chicken.

This might be the pseudocode for that program:

preheatOven(400);

placeChicken(4, "baking dish");

spreadMustard();

bake(400, 30);

An example that uses an algorith to solve a math problem is more relevant to our pursuits. Let's describe an algorithm to evaluate the sum of a sequence of numbers 1 through N.

SUM(N) = 1+2+3+...+N

Where N is any given number greater than zero.

Translating the preceding algorithm into code, we have:

let sum = 0;

let n = 10;

let i = 0;

while(i <= n) {

sum = sum + i;

i++;

}

console.log(sum);

Traditionally, programming is thought of as the process of:

We have just done this in the chicken and summation examples.

Some ideas, however, are too large to be finished in one fell swoop.

So, our revised process is:

This does not mean to say you shouldnt experiment along the way, even altering the original idea completely. And certainly, once the code is finished, there will almost certainily remain work to do in terms of cleaning up the code, bug fixes, and additional features. It is this thinking process, however, that should guide you from idea to code. If you practice developing your projects with this strategy, creating code that implements your ideas will hopefully feel less daunting.

We will practice with a very simple game.

Lets describe the game in paragraph form.

***Rain Game***

The object of this game is to catch raindrops before they hit the ground. Every so often (depending on the level of difficulty), a new drop falls from the top of the screen at a random horizontal location with a random vertical speed. The player must catch the raindrops with the mouse with the goal of not letting any raindrops reach the bottom of the screen.

Exercise - Write out an idea for a project you want to create

Now this is extremely tricky. Let's try to make it similar to the game we're creating.

My game:

The object of this game is to find the word before the first letter hits the the bottom of the screen. A series of letters will appear at the top of the screen at random horizontal location with a random vertical speed. The player must catch the correct letters with the mouse with the goal of spelling the correct word. If the player catches three incorrect letters, that player will lose.

Now let's see if we can take the "Rain Game" and break it down into smaller parts.我们该怎么做? For one, we can start by thinking of the elements in the game: the raindrops and the catcher. Secondly, we should think about these elements' behaviors. For example, we will need a timing mechanism so that the drops fall 'every so often'. We will also need to determine when a raindrop is 'caught'. Let's organize these parts more formally.

Part 1. Develop a program with a circle controlled by a mouse. This circle will be the user controlled 'rain catcher'.

Part 2. Write a program to test if two circles intersect. This will be used to determine if the rain catcher has caught a raindrop.

Part 3. Write a timer program that executes a function every N seconds.

Part 4. Write a program with circles falling from the top of the screen to the bottom. These will be the raindrops.

Parts 1 through 3 are simple and each can be completed in one fell swoop. However, with Part 4, even though it represents one piece of the larger project, it is complex enough that we will need to complete this exact exercise by breaking it down into smaller steps and building it back up.

Exercise - Take my idea and break it into individual parts.

Part 1. Same as Dan's - Develop a program with a circle controlled by a mouse. This circle will be the user controlled 'letter catcher'.

Part 2. Same as Dan's, since each letter will reside inside of a circle (I just thought of this). Write a program to test if two circles intersect. This will be used to determine if the letter catcher has caught a letter.

Part 3. Write a program to determine if the letter catcher has found a letter in the word. If it has, add the letter (and all circles with the same letter) to the screen. If it hasn't, add one strike.

Part 4. Same as Dan's - Write a timer program that executes a function every N seconds.

Part 5. Write a program with circles falling from the top of the screen to the bottom. Inside each circle will be a letter. These will be the letters for the words.

I actually think I'm going to program the UFO game, same as from Stanford 106A.

Step 1: Write a function that draws a rect at the top right corner. Call it 'UFO'.

Step 2: Write a function that makes the UFO move from the top to the right to the left of the screen, then from the left to the right of the screen, moving down the screen as it reaches each edge of the screen. If the UFO reaches the bottom of the screen, the game is over.

Step 3: Write a function that creates a small circle at the bottom center of the screen, called 'Bullet', when the mouse is clicked.

Step 4: Write a function that makes the bullet move from the bottom center of the screen to the top of the screen.

Step 5: Write a function that detects when the Bullet intersects with the UFO. If this happens, make the UFO disappear and display 'Game Over'.

We will now follow this process for each part:

If we do our job correctly, all of the functionality needed will be built into a class which can then be easily copied into the final project itself.

This is the simplest part to construct and requires little beyond what he learned in Chapter 3. Having pseudocode that is only two lines long is a good sign, indicating that this step is small enough to handle and does not need to be made into even smaller parts.

伪代码:

Translating it into code is easy:

function setup() {

createCanvas(400, 400);

}

function draw() {

background(255);

stroke(0);

fill(175);

ellipse(mouseX, mouseY, 64, 64);

}

This is a good step, but we are not done. As stated, our goal is to develop the rain catcher program in an object oriented manner. When we take this code and incorporate it into the final program, we will want to have it separated out into a class so that we can make a 'catcher' object. Our pseudocode would be revised to look like the following:

设置:

画:

Here is the Catcher class.

Part 2 requires us to determine when a catcher and raindrop intersect. Intersection functionality is what we want to focus on developing in this step. We will start with a simple bouncing ball class (which we saw in Example 5-6) and work out how to determine when two bouncing circles intersect. During the 'integration' process, this intersect() function will be incorporated into the Catcher class to catch raindrops.

Here's the algorithm for the intersection part.

设置:

画:

The hard work here is the intersection test, which we will get to in a moment. First, here is what we need for a simple bouncing "Ball" class without an intersection test.

数据:

功能:

We can now translate this into code.

From here it is pretty easy to create a sketch with two ball objects. Ultimately we'll need an array for many raindrops, but for now, two ball variables will be simpler.

Now that we've set up our system for having two circles move around the screen, we need to develop an algorithm for determining if the circles intersect.

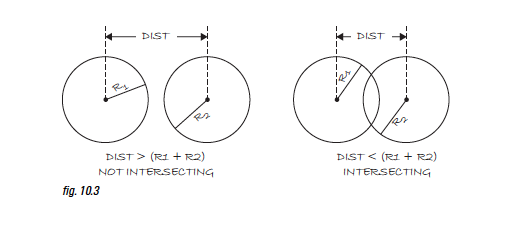

In p5.js, we know we can calculate the distance between two points using the dist() function. We also have access to the radius of each circle (I've been calling it r but it's actually d(diameter, or width) I think. To find radius I would need to divide d by 2). See the image below - we can compare the distance between the circles and the sum of the radii to determine if the circles overlap.

OK, so assuming the following:

We have the statement:

If the distance between (x1,y1) and (x2,y2) is less than the sum of r1 and r2, circle one intersects circle two.

Our job now is to write a function that returns true or false based on the above statement.

// A function that returns true of false based on whether two

// circles intersect

// If the distance is less than the sum of radii the circles touch

function intersect(x1, y1, x2, y2, r1, r2) {

let distance = dist(x1, y1, x2, y2); // calculate distance

if(distance < r1 + r2) { // compare distance to r1 + r2

return true;

} else {

return false;

}

}

}

Now that the function is complete, we can test it with data from ball1 and ball2.

let intersecting = intersect(ball1.x, ball1.y, ball2.x, ball2.y, ball1.r, ball2.r);

if (intersecting) {

console.log("The circles are intersecting!");

}

The code above is somewhat awkward and it will be useful to take the function one step further, incorporating it into the ball class itself. Let's first look at the entire main program as it stands.

I'm pretty sure Dan has videos about this too, so I'll check that out next.

Here's Dan's first video about Object Communication.

We should, however, program this in an object oriented fashion. We should have an intersect funtion inside the Ball class that returns true or false.

Now we have learned that an object can have a function that takes another object as an argument. This is one way to have objects communicate. In this case, they are checking to see if they intersect.

Our next task is to develop a timer that executes a function every N seconds. Again, we will do this in two steps, first just using the main body of a program, and second, taking the logic and putting it into a Timer class.

p5.js has the functions hour(), second(), minute(), month(), day(), and year() to deal with time. We could conceivably use the second() function to determine how much time has passed. However, this is not terribly convenient, since second() rolls over from 60 to 0 at the end of every minute.